A Good Man

Oct 5, 2017

Nā Daniel Bartlett

In the 1980s the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board began grappling with the issue of developing a governance structure with its own legal personality with greater accountability to its people and that could deliver what Ngāi Tahu needed for its post-settlement future. Its first attempt was the creation of Te Runanganui o Tahu in 1990 under the Incorporated Societies Act, a precursor to Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.

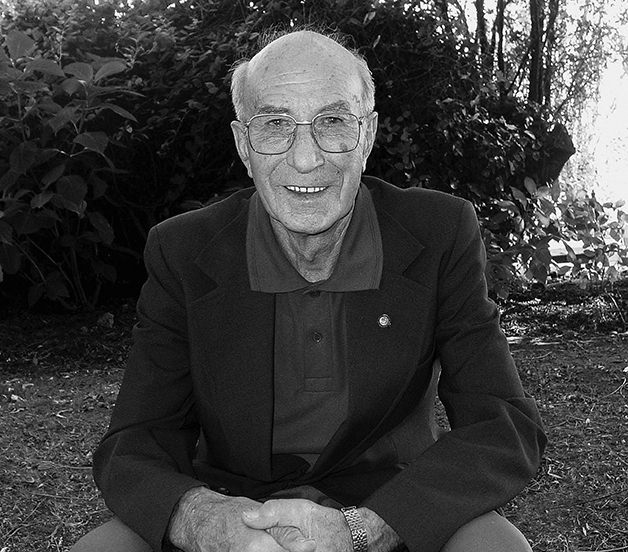

Kelvin (Kelly) Mervyn Anglem, from Arowhenua, was the first kaiwhakahaere of Ngāi Tahu, heading Te Rūnanganui o Tahu until ill health forced him to retire in 1993. A close friend, cousin, and neighbour of my pōua Carlyle (Carl) Walker, Kelly is a man I have only ever heard spoken of in the very highest regard. Indeed, whenever his name comes up, my mother will say, “He was such a good man.” When I heard that TE KARAKA was planning a profile on Kelly, I proffered my services without hesitation. I grabbed a recorder and a raincoat, and headed south on State Highway 1 to go and talk to Pōua.

Kelly was born in 1930, and grew up at Waipopo, on the banks of the Ōpihi River. The small South Canterbury settlement is found 10 kilometres south-west of Temuka. Kelly’s mother was Minnie Te Waimakariri Anglem, and he was brought up by his grandparents, Mereana Tarawhata Waaka (Aunty Piriha) and Walter (Wally) Te Maiharanui Anglem, who legally adopted him. He attended Seadown School and then Timaru Boys’ High School, before going to work on Rollesby Station, at Burkes Pass in the Mackenzie Country.

Kelly was renowned for his wisdom and understanding of whenua, whakapapa, and mahinga kai. My pōua Carl describes him as being “very knowledgeable”.

“He learnt everything from his tāua and pōua when he was a child, and it was instilled in him all the way up.”

Kelly would later draw upon this mātauranga Māori in support of his hapū, his iwi, and Te Kerēme.

This expertise was just one of the many reasons that Kelly was appointed the first kaiwhakahaere of Ngāi Tahu, when Te Rūnanganui o Tahu Incorporated was established on 5 October 1990.

Another was his ability to remain calm when there was kōrero in the whare. “He would just listen and talk quietly,” says Carl. “Some people start talking over you when they think they know everything. He wasn’t like that. He was a real gentleman.”

Kelly was actively involved in many committees, including the Arowhenua Rūnanga and the Waipopo Trust. “He wasn’t on [the Waipopo Trust] for a start. Then Mick O’Connor said, ‘Get Kelvin’. And so we went down and asked him to come and join us. So he joined us then and was with us ever since,” says Carl.

Alongside his mahi for the iwi, Kelly worked as a stevedore on the Timaru wharf for over 30 years – responsible for loading and unloading the ships in port. He married Eunice Margaret Walton (Margaret or Aunty Pop) in July 1956, becoming stepfather to her children, and later, a father to their daughter Christine. Kelly and Margaret were devoted and loving parents. Christine describes her parents as “two of the most remarkable people I have ever met … community, teamwork and family were very important in our house.”

Kelly took the children to the Ōpihi River to teach them how to bob for eels using harakeke, to lay down hīnaki, to hand line and spear fish, and to whitebait. As well as these practical skills, Christine says that her parents taught the children “many things. A work ethic second to none, that all people are created equal … [and that] if you had knowledge, share it; your children and grandchildren are your future.”

The whānau lived in Timaru, but in later years Kelly and Margaret returned to live at his papa kāika, Waipopo, where they built a house. Carl says that Kelly reckoned “it was the best thing that ever happened, because if anything went wrong he could just walk down the road and get me, or I’d go up and get him.”

“He would just listen and talk quietly [when there was kōrero in the whare]. Some people start talking over you when they think they know everything. He wasn’t like that. He was a real gentleman.”

Carlyle (Carl) Walker

When I asked Gwen Bower, Kelly’s niece, for her earliest memory of him, she enigmatically replied, “3868”. In response to my obvious bemusement, Gwen, who is now the Arowhenua Marae manager, elaborated: “For some reason, I used to ring up Aunty Pop and

Uncle Kel, quite frequently, and sing ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’. So I learnt their telephone number, which was 3868.”

The families were all very close, says Gwen, “because of Dad, Uncle Lallie [Carlyle Walker], and Kelly all being brought up down at Waipopo, and spending a lot of time with their tāua and pōua.”

Kelly and Margaret “lived up the hill from us, around on Andrew Street [in Marchwiel, Timaru], so we frequently went up there to see them. And Christine. And Judith, Michael, David, and Peter – they were the children from Aunty Pop’s first marriage.

“All throughout our lives Uncle Kel and Aunty Pop were really, really strong role models for us.”

In the 1980s Kelly helped the Māori Affairs Department when they were setting up work schemes in the region. Gwen remembers that he was “always helping people with their whakapapa and with land issues.” Kelly and Margaret were actively involved in the wider community, and Kelly was “highly regarded in every tauiwi group you can think of,” says Gwen.

He was also a staunch defender of the environment, and in 1988, when he spoke of his bucolic childhood to the Waitangi Tribunal, it was with a sense of sadness at the changes that had taken place:

“I recall as a child from the age of four onwards, being taken by my grandparents each year, on a night in March, across to the North bank (Milford side) of the Ōpihi River immediately opposite our home. We would anchor our boat under the willows, and using the moenu or bob, we would proceed to catch our winter supply of eels… These eels were cleaned, dried, and preserved; some being used as barter for other foodstuffs [and] the remainder as a winter food supply.

I also recall in March 1944 going towards the river mouth one night and coming upon the Heke – the migration of the eels to the sea to spawn. The river mouth was blocked, and the eels had elected to travel overland and across the shingle beach to the sea. I picked out of the grass and shingle as many eels as I could carry in the space of 15 minutes. Alas, 1988 tells a different story.”

Identifying river realignment, removal of willows, commercial fishing, irrigation, and pollution as the main culprits in the declining eel population, Kelly quoted the Timaru Herald’s recent description of the Ōpihi River’s deplorable transformation “from a recreational resource into something unfit for dogs to swim in.” And it was with regret that Kelly averred, “I am glad my tūpuna cannot stand on the banks of the Ōpihi and see what I have stood back and allowed to happen.” A man with an innate sense of what was right and what was wrong, Kelly’s integrity was manifest when he outlined to the Waitangi Tribunal his grave concerns about the machinations of commercial polluters. Highlighting a Timaru company that had agreed to improve the quality of the effluent it discharged into the Washdyke creek, Kelly was not afraid to speak truth to power:

“About two months ago at the expiration of its current entitlement, this company applied for an emergency water right, citing as its reason the non-arrival from overseas of equipment needed to improve the quality of effluent. They further went on to say that, should they not be granted this emergency water right, the company would have to seriously consider moving their operation to Christchurch. I suggest that this is not an isolated case where these sorts of pressures have been used by commercial operators, and in the light of the present economic climate and the high rate of unemployment in Aoraki, these tactics are nothing short of industrial and political blackmail, effectively rendering useless any powers that water boards and other regional authorities may have … we need to remember that we do not live in a land that was left to us by our fathers, but rather a land that we have borrowed – TEMPORARILY – from our children.”

Kelly passed away in 2006, aged 76. In a fitting testament to a Ngāi Tahu leader, indefatigable worker, and genuinely good man, Gwen remembers him thus: “To me, he was a person of integrity and mana. He was humble with it, and willing to share his knowledge.

And it wasn’t just for Māori … him and Aunty Pop were highly thought of in other circles too. At work, he always had that strong sense of integrity. He had mana wherever he went.”