A Tangata Turi whakapapa ki Ōtautahi

Dec 21, 2021

How a staunch wahine of Scottish and Te Aitanga a Māhaki whakapapa became mother to the Deaf community in Ōtautahi and triggered a robust kōrero about Tangata Turi within Ngāi Tahu. Kaituhi Arielle Kauaeroa learns more.

Above: Haamiora (Sam) Te Maari in kōrero with Karen Coutts at his old stomping ground, formerly known as the Sumner School for the Deaf and Van Asch College.

Margaret Duncan was born in te tai rāwhiti to parents Archie and Laura Duncan and, as a baby, was struck by scarlet fever. At a time when antibiotics were not readily available, she was lucky to survive, but was left profoundly Deaf. Yet to describe her Deafness as a loss seems at odds with the proud woman who became known for her work bringing so much gain to the Deaf community of Aotearoa.

Although Margaret began mainstream schooling in Gisborne, it wasn’t long before the entire Duncan family travelled to Ōtautahi so their pōtiki could attend the only School for the Deaf in the country. To relocate a family in the 1930s, not only across the country but to another island, was an incredible feat – one driven by the desire of loving parents for their daughter to access education.

Margaret often shared with daughter Karen that it was her mother and grandmother, Laura and Jemina, who ensured she always had an active place in the family. With so little support for parents of Deaf children in those days, Laura’s ability to include her youngest child in family affairs undoubtedly shaped Margaret’s role as a giant in the Deaf world.

Haamiora Samuel Te Maari (Sam) attests to this. As a young Deaf Māori man, watching Margaret move in the world of the Deaf and hearing was awe-inspiring.

“She was Māori, and she was our leader, a great leader. Her mum, [pointing to Karen], she always got everyone together, she always brought us in. We loved her beyond belief.”

Sam (Ōnuku, Wairewa, Koukourarata) is using New Zealand Sign Language and Karen is interpreting for us.

“Her mum was something else, she was so successful, and we couldn’t understand how she did it. But she always made us believe we could do it too.”

Margaret’s path intersected with Ngāi Tahu when she met the love of her life, Morris Coutts, at the Deanes clothing company where they both worked in Christchurch. Recently returned from active service in Egypt and Italy, Deafness was no barrier for Morris (Moeraki, Awarua, Waihao, Ngāi Tūāhuriri). They married in 1948 and, as parents of three hearing daughters, the Ngāi Tahu tāne and Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki wahine raised their whānau predominantly in the Deaf world.

Margaret became the first woman and Māori president of the Christchurch Deaf Club, co-founded the Deaf Women’s Group and Deaf Aotearoa, and championed for Deaf rights, including being recognised as a cultural and linguistic group, for improvements to Deaf education and social access. Her main love was Deaf sports, which she was actively involved in, and frequently represented the New Zealand Deaf Sports Association at international congresses. In 1990, she was recognised with the New Zealand Commemoration Medal. Morris, always in support, was awarded the Companion of the Queen’s Service Order for services to the Deaf community in 1982. At the birth of their first baby he had a flashing light alarm invented so Margaret could be alerted when their pēpi cried; he established the Christchurch Relay Service for Deaf people and helped to establish the New Zealand Deaf Sports Association. He was also the main planner to win the bid and organise the Christchurch World Games for the Deaf in 1989.

Margaret survived Morris by 31 years, continuing their shared mahi for many of those before transitioning into the realm of Hine-nui-te-pō herself in 2017, just before her 90th birthday.

Above: Margaret and Morris Coutts were dedicated to the Deaf community of Aotearoa.

Moving between both worlds, Karen Coutts continues to carry her parents’ standard today. Tū maro ia, she stands long and strong in the face of oppression to advance the position of her people, in a tribal setting as a former Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu representative for Moeraki and as an advocate for Deaf Māori.

“This is not my story because I’m not Deaf. I live in this world, but it’s Sam’s story, it’s my Mum’s story … all I want to do is tautoko Sam to carry on the legacy that Mum and Dad started with their work. That’s the job, to make it even better for our whānau with each passing generation.”

And it is a hard thing, Karen says, for whānau Māori to understand and accept when we are falling short for vulnerable whānau as iwi, as hapū.

“There’s no support for Deaf Māori to participate on the marae, or at hui. There’s no missing when our community is present, we’re signing, waving our arms all over the place and making sounds nobody else is making … so if that’s not present, we are outside. If you’re the oppressed one, how do you get in? And isn’t that what we’ve been asking Pākehā for – space for us as Māori to participate?

“Those who are oppressed often do not understand that they can be the oppressor. We are fighting as Māori to preserve our language, to push back, but we have not thought enough about whether we are doing the same to our own whānau.”

Karen’s kōrero may be challenging for some, but her truths are steeped in decades of experience as a hearing person involved in family, community life and advocacy within the Deaf and hearing worlds. For 15 years, Karen worked as a social worker for the Deaf in London and, living in the Deaf Māori community here, she has witnessed the isolation and exclusion tangata turi experience daily.

She recalls working with a man named John – “like a lot of older Deaf people, particularly men, he’d grunt a lot and people were quite scared of him, but I really loved him.” When asked who he had spoken to during the day, he replied that at 5am his boss had said ‘hello’.

“I struggled to understand how he could even stay sane in a world like that where one word of communication per day was enough. Deaf people have had to be profoundly resilient.”

And from an Indigenous perspective, this is even more true.

“Being Māori and Deaf, it’s a dual oppression. At school we were discriminated against more because we were Māori, especially the older ones, there are really sad stories,” Sam says.

“In the old days, Sumner School for the Deaf, it was different from my time. Those old Deaf people, they got the wooden stick. If they didn’t learn how to write, they would get hit. The education was much worse, the oral education was so strict back in those days.”

“There’s no support for Deaf Māori to participate on the marae, or at hui. There’s no missing when our community is present, we’re signing, waving our arms all over the place and making sounds nobody else is making … so if that’s not present, we are outside. If you’re the oppressed one, how do you get in? And isn’t that what we’ve been asking Pākehā for – space for us as Māori to participate?

“Those who are oppressed often do not understand that they can be the oppressor. We are fighting as Māori to preserve our language, to push back, but we have not thought enough about whether we are doing the same to our own whānau.”

Karen Coutts

Education was just one way the oppression occurred, particularly under the national and global approach to educating Deaf people in oral instruction. At the Milan Conference of 1880 it was decided by hearing people that the oral method was superior to signing and that Deaf people should assimilate into the dominant oral culture. This meant Deaf students were taught by hearing teachers with oral language by using lip reading, speech, and mimicking the mouth shapes and breathing patterns of speech, which led to the suppression of gesture and sign language as valid forms of communication.

New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) was recognised as an official language in 2006 and manualism (sign language) is now the accepted mode of education for Deaf and hard of hearing students, both significant triumphs.

Karen recalls her time working as a policy analyst on the first iteration of the New Zealand Disability Strategy (2001) and the difficulties she and her colleagues faced trying to ground disability discourse in Māori culture.

“Hemi Ririnui Horne was the lead advisor and we both did a lot of work trying to find where disabilities sit within te ao Māori. Within Judeo-Christian society, or Western society, there’s plenty of examples in the narratives that disabled people existed. There are stories in the Bible, there are wonderful pieces of literature – everybody knows about the hunchback of Notre Dame. So, there’s a presence of disability in the community that we historically know about. But we could not find whakataukī, stories from the old people, anything that pointed to or highlighted disabled presence in te ao Māori. I sense this is because as Māori we operate as a collective, we don’t operate as individuals, but it did make things difficult for that work. There was no reference point to hang on to.”

Karen and Sam discuss the many challenges Deaf Māori face in participating in te ao Māori and, although Māori Sign Language is developing thanks to ground-breaking work by Deaf tāne Patrick Thompson and sign language interpreter Stephanie Awheto, there is limited capacity in the Deaf world and in te ao Māori to share, learn and offer interpreters at marae and hui.

Above: Sam and Karen have a laugh outside Tuawera, the whare onsite at Ko Taku Reo, as his former school is now known.

“Even for tribes who are well-established like Ngāi Tahu, taking care of these people’s needs is not top of the list,” Karen says.

“Within the Māori world generally, I think disability is the last bastion to be fought for. I don’t think we’ve really realised what disability participation means. Just being able to go to the marae does not necessarily mean you’re able to participate.”

Sam attended a tribal hui at Ōnuku in 2017, much to Karen’s surprise. She often lets Sam know when hui or events were happening but, due to inaccessibility, he rarely felt able to take up the call. As the Moeraki representative for Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, whānau were more than surprised when Karen became the impromptu NZSL interpreter for the hui.

So how can iwi, hapū and hapori do better for our Deaf whānau?

“Interpreters should be resourced ahead of time so that whānau feel safe and comfortable to not only attend, but also participate. It should be normative.”

Karen was asked more than once at the hui: how many Deaf Ngāi Tahu are there. Her answer?

“How would I know – the tribe has a better chance of finding that out than me if it wants to. Because with all modes of disability, participation is limited when a social model of oppression is present and that is usually because no-one understands that it’s happening. There’s nothing inherently wrong with being different, but at a mainstream level building inclusivity is not a priority.”

Even, apparently, in te ao Māori, a culture in which we pride ourselves on participation of and for all – mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei.

“I think we need to ask ourselves, where’s our manaakitanga? Where’s our whanaungatanga?

“We have an opportunity as a tribe to support whānau, especially parents of Deaf tamariki, to feel confident that providing a tri-lingual home and environment is possible. I am fluent in English and NZ Sign Language and my te reo is now good enough that I have a basic working conversational capacity – we can absolutely do this. It’s a good time to assess what we as a tribe do to provide access to all Deaf whānau, otherwise excluded from active participation in our cultural tribal life.”

Tangata Turi ki Ngāi Tahu rangatira Haamiora Samuel Te Maari has had enough of being on the outer. He is one of a growing number of Deaf Māori ready to claim their birth right to participate in their culture.

“I was born in the Taranaki in Hawera. I was born hearing but became Deaf after that. We moved to Christchurch in 1968 because my father had got a job here and he wanted to be close to my uncle. My parents were trying their best to give me an education and I attended Sumner School for the Deaf from five years old, but then spent time in Deaf units in Philipstown and Linwood schools.”

Sam, exclusively taught orally in his primary schooling, was eager to return to the Sumner school to experience full immersion with other Deaf children.

“Māori Deaf have been stopped from signing and from learning about Māori culture. We haven’t been able to take this for ourselves. Many of us don’t know our whakapapa and we can’t find each other easily, but the desire to grow is there. We want to be together, we want to start this and to work with the kupu, to understand what they mean so we can start relating to the language.”

Haamiora Samuel Te Maari (Sam)

“I was highly motivated to get back. I could see the difference – they were all signing and communicating with one another. I hadn’t learnt any of that under the oral speech therapy approach. It just made me frustrated, I had to keep repeating things and kept being corrected.”

Our interview is the first conversation I have had with a Deaf person and the irony is not lost as I write about how we as Māori marginalise our whānau tangata turi. I didn’t want to be ignorant or rude and I’m not sure how to ask questions. Karen interprets for me: “How should I ask questions? I don’t want to interrupt.”

“If you need to be clear, interrupt, that’s fine.” Sam says, smiling. “Bring it on!”

Together, they explain that in conversation with Deaf people, interruptions are typical – but in a way which is quite different from oral interruption. It is usual to check everyone in the conversation is receiving the correct message and clarity is paramount. They demonstrate the sign to interrupt, and we return to the conversation at hand.

“Nine out of 10 Deaf people are born to hearing parents who don’t even know there is a Deaf world,” Karen says.

“Most parents with Deaf children have never met a Deaf person before. They’re scared, and they want their child to grow up well, so they take whatever advice they are given.”

Sam says he absolutely felt loved, but the communication barrier made it hard to connect.

Sam says he absolutely felt loved, but the communication barrier made it hard to connect.

“In the school, when they were teaching me oral therapy, the teachers would tell me how good I was at speaking and I couldn’t hear so I didn’t know any better, I thought I was doing OK. Then I’d go home and try to talk but it still wouldn’t work – the whānau would still be saying to me ‘what are you going on about?’

“So, I didn’t want to be around the family much. Then one day a friend and I were out on a bike ride and signing at the same time. All of a sudden we saw a man coming towards us, waving. He signed: ‘I saw you’re Deaf’ and we said ‘Yeah? And who are you?’

“Mr Pruden was his name. We were amazed, it was such a role model to see a Deaf man out in the world. At the school, all the teachers were hearing, only the children were signing. We’d never met a Deaf adult so we didn’t understand that there were older Deaf people. The three of us became really good friends.

“At that time, I was 12 or 13 and he must’ve been older than 80. And he gave me so much information about where I should be going and who I should be talking to, how to find the Deaf community. The whole world opened up.

“I went home and told my family that I’d met this old man and it was so exciting, but they couldn’t get how important it was for me … it was hard, but that’s life. If you’re Deaf you have to learn about life being Deaf. You can’t give up, you’ve got to accept life is not fair, life is tough and, if I’m going to enjoy being me, I accept that as a Deaf person I am oppressed. And I go, ‘forget it, I’m carrying on’. Even with the family, you have to move on, oh well!

“I talked to two of my mates about this Deaf club Mr Drew had told us about and we made a plan. I was so nervous. Was I allowed to go in? We didn’t know. But it was lovely, there were so many Deaf people there. It increased my confidence so much, it wasn’t complete, but I could immediately feel there was some kind of boost.

“At school, they would give us problems to solve and, being taught orally, it was hard to read and write. I’d put it in my pocket, and I should’ve gone straight home, but I didn’t do that of course – I’d go off to visit some Deaf adults and get them to help me. They always gave me the time, they were so welcoming, nearly every day I’d go and get help.

“My parents were a bit worried because I started coming home late every day. I never told them where I was going or what I was doing, I had to keep it secret, or they would stop me from going. I was being helped, I was learning too, and I didn’t want that to stop.

“The school teachers thought I was ignoring them, but that wasn’t true. There was no doubt I wanted to learn, but I couldn’t learn through the ways they taught. My parents would tell me off because I wasn’t trying hard enough, and I’d try to communicate to them what was going on. The oral system, it didn’t help at all.

“I’d go to the Deaf adults and get the help I needed with signing, and I’d be so much better behaved at school because I was learning – learning to even put up my hand and say, ‘I don’t understand, please make it clearer so I can learn’.”

Karen says the Deaf club (now known as Te Kāhui Turi ki Waitaha – Deaf Society of Canterbury) is a place for community connection and traditionally it was where Deaf people gathered and organised social and sports events.

Sam says that for some reason the generations before him seemed to have caught on to English better, like Karen’s mum, and it was through them his comprehension grew. Karen theorises this was because, although the schooling was even more harsh than in Sam’s time, they had a strong community in the Deaf club to help each other.

“They faced worse discrimination, so they all knew they had to help each other. Nobody was going to organise a Deaf club for them, so they had to do it for themselves. They had to learn how to improve their writing, so they could write to places to get help. Usually, they had one or two family members they could ask for help.”

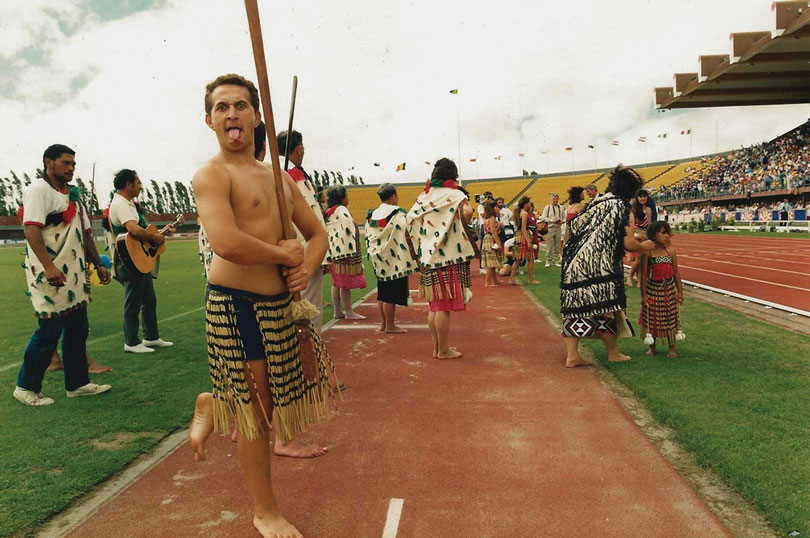

Above: Sam at the World Deaf Games after performing the wero.

Sam agrees. “When I first met Deaf adults I asked them if they could drive and yes, of course they could. I asked, could I drive? And they laughed and said of course. But my parents had always said, ‘you can never drive. You are Deaf. It would be a risk, you can’t drive.’”

As a young man Sam began training as a welder at Christchurch polytechnic.

“I needed to be independent. I wanted to learn how to live. The family would’ve kept me stuck, so I had to get out. They were so worried about how I was going to cope, but I was fine. Mum and Dad had both expected they would have to take care of me for the rest of their lives. They were stunned when I got my first job!”

Sam’s welding career has spanned 42 years. He also became a pāpa at a young age with former wife, Brenda Williams, who is also Deaf.

“Being a new father, it gave me a bit of a shock. We had to learn, and Brenda’s parents, who were both Deaf, signed with us to teach us everything we needed to know.”

Sam and Brenda’s four children are hearing. They attended Addington School and “were a bit shocked with the hearing world, as they’d been raised in the Deaf world.”

“It was a bit hard at first for my boy, learning English and all of that, but he got good support. I didn’t want my children to have what had happened to me. I wanted us to be able to fully communicate and to still get the best of what they needed.”

While attending festivals and events at marae with his parents, being Deaf Sam didn’t have a connection with his culture so with confirmation that the World Deaf Games would be hosted in Christchurch, a new challenge was presented.

“In 1989, we were set to host the World Deaf Games in Christchurch and Karen’s mum, she got us organised at the Deaf club. She asked for us all to support her, to be prepared for Christchurch to host the games. We said ‘yes, what do we have to do, what do you need from us?’

“She was wahine toa, we couldn’t ignore her and if she said something, that’s our mother, we have to do it. We didn’t have many signers at that time, so we had to teach some hearing people to sign a little bit. And as it got closer, her mother said to us, ‘I need to see the Māori Deaf. You need to do the pōwhiri’.

“I was thinking ‘oh no’, looking around. I thought I didn’t know enough; I hadn’t been involved enough in the Māori world. But straight away she was at me. I had to train, I had to learn. We went to Rehua Marae to ask for help, three of us tāne and one interpreter. At that time, interpreters couldn’t understand the reo because there wasn’t Māori Sign Language, so we were missing information, and it was a very challenging situation. Emotionally challenging, spiritually challenging.

“But I wanted to do it, I felt I had to do it. To tell you the truth, never before had I held the taiaha. That day, when we had the opening with the Deaf world watching, I was so nervous but determined, I couldn’t back out. When I put the wero down, I could see the president’s face, I could see he was taken aback. As I moved back, I felt really good … like ‘yeah, I am part of this’.

“After everyone had gone home, I was still thinking about it for a long time. And I felt there was something I had to deal with here. Where is my Māoridom? Where is it?”

Today, Sam does a lot of work with Deaf Māori tamariki and sees the positive changes in education for the Deaf and hard of hearing, and within wider Aotearoa society.

“But when I look at Māori Deaf, I can’t see it happening for us at this time, I can’t see doors opening for us. There are so many extra layers to struggle through.”

In his work addressing linguistic exclusion from the Deaf world and social exclusion from the Māori world, Sam believes iwi have a role to play.

“Māori Deaf have been stopped from signing and from learning about Māori culture. We haven’t been able to take this for ourselves. Many of us don’t know our whakapapa and we can’t find each other easily, but the desire to grow is there. We want to be together, we want to start this and to work with the kupu, to understand what they mean so we can start relating to the language.”

Karen is committed to supporting and mentoring Sam in his voluntary role with Tū Tangata Turi, a rōpū of Deaf Māori from across Aotearoa who are organising around their cultural intersections. It’s an uphill battle a lot of the time, but she remains hopeful that a growing awareness of the Deaf and disabled communities within te ao Māori will inexorably keep positive change moving forward.