Whare uku: Earth Dwelling

Oct 17, 2012

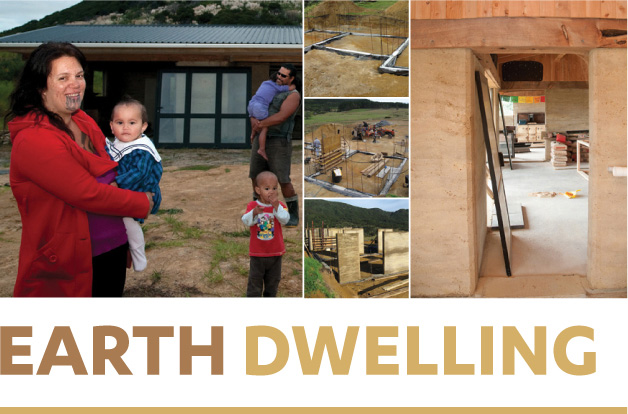

Taking ownership for their whānau tino rangatiratanga is the motivation behind a young couple’s adoption of an innovative new way to build their home in Ahipara, Northland. Kaituhituhi Jeff Evans reports.

For Heeni Hoterene and Rueben Taipari Porter building a home from earth, sand and muka, resources all harvested from ancestral land, has a deep spiritual resonance.

The couple first became aware of the potential of rammed earth as a building material on a trip to Europe in 2008 when they had an opportunity to stay with local families.

Heeni, who is Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Raukawa, saw how their hosts were living in homes that had been in their families for hundreds of years. “Because they were long-lasting, low maintenance homes that had been in the family for generations, our hosts could afford to be very generous to us.”

Māori have always been judged on the ability to provide for manuhiri, so access to sustainable wealth is inextricably linked to enduring mana, she says.

Back home in Ahipara, the pair had a chance meeting with John Jing Siong Cheah, a PhD student in the University of Auckland’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, who is involved with the fledgling whare uku programme.

The whare uku concept was originally conceived in 1994 by Dr Kepa Morgan (Ngāti Pikiao, Te Arawa, Ngāti Kahungunu, Kāi Tahu – Kāti Kurī, Kāti Huirapa), now an associate dean at the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Auckland. Kepa was looking into options for an affordable and appropriate housing system for rural Māori.

Among the attributes needed for rural housing were a construction technology that could be easily adopted by a non-technical workforce, designs requiring minimum input from professional engineers, and a finished home with a lifespan of at least 150 years.

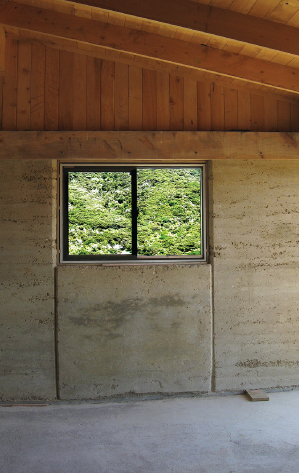

The interior showing the thickness of the rammed earth walls.

As Heeni explains, building a whare uku style home is a perfect fit for their lifestyle and beliefs, which include using local resources wherever possible.

“The sand was sourced locally. The earth was from our whānau land, as was the muka fibre, which was harvested from harakeke planted by Rueben’s father.”

The use of muka as the binding agent to strengthen the walls was especially poignant for Heeni. “The muka appeals because it is something familiar: it’s Māori and traditional and it’s a taonga.”

Rammed earth has significant advantages over traditional materials such as brick and timber. As well as giving a unique look to the dwelling, the walls of whare uku contribute to a healthier home environment.

Another major benefit is that despite being 200 mm thick, the walls are breathable. They are not sealed and plastered, and act as filters, significantly reducing airborne irritants in the home.

Heat retention is yet another plus. “The walls actually soak up any heat entering the room,” explains Heeni. “The walls are like hāngī stones. They heat up during the day and then slowly release warmth over an extended period of time.”

Building quality homes that require little maintenance and last for generations is a proven way forward to whānau wealth.

Rueben says while many families in the North are cash poor, many have natural resources available to them, and many whānau have come back from the city in the last few years with the right skills.

While there is a good deal of Māori land in Northland that could be used for housing projects, the couple acknowledge that working with a council can be a major challenge for some.

Heeni and Rueben have worked closely with the Far North District Council to have rammed earth signed off as a legitimate building material, documenting the process along the way.

“We are more than happy if people want to come and check out what we’re doing,” says Heeni. “We’ve recorded how we’ve done things, and we’re willing to offer that knowledge to other whānau. That is our koha back to everyone who has helped us along the way.

“So we are saying: ‘If you want the architectural plans, here they are. If you want the engineering specs, here they are. If you want to know how we worked with the council, here it is.’”

Heeni says whare uku can bring mana back into the lives of all Māori. “Māori are rangatira, so we need to live in houses fit for rangatira. Our people shouldn’t live in illegal or substandard housing.”

A common response from visitors seeing the house, due to be finished in October, is to say: “Oh, it is a real house!” Heeni says with a laugh.

“I’m sure some of them imagine it is going to be a little African mud hut. But it is really just like any other house.” The only real difference is the materials used for the walls.

While the construction has been spread over many months as they work through the council requirements, the actual build time is around two-and-a-half months.

“If you have everything in place: all your materials and your work crew, we can build two to three walls a day: and I think we had 30 walls in total,” says Heeni.

“The majority of the time is spent waiting for everything to set, especially the foundations and the concrete ring beam that sits around the top of the walls.”

Local youth were trained in rammed earth techniques while Rueben oversaw the construction of 18 practice walls. When the roof was put in place a number of individuals lent their expertise, once again proving the value of whānau support.

“We are quite proud that the house is built like that, with many, many different people coming together and offering their skills.”

Along the way they have identified opportunities for Māori agencies to work collaboratively to help reduce the cost of future homes.

For instance, building consents require a geotechnical report from a drain layer that can cost in excess of $2000.

Rueben says there is an opportunity for rūnanga to assist individuals to enter that profession, and once they have qualified, for the rūnanga to subsidise the reports for their own iwi. The same opportunities are there for surveying and the waste system consultants.

At the moment the build cost for the whare uku is $100,000, but Rueben says he hopes to trim the completion cost for future new homes significantly.

“We have some opportunities on the horizon that will allow us to refine our processes, with the ultimate aim of eventually reducing the cost of building a whare uku home to around $50,000.”

One exciting prospect is a developing partnership with He Korowai Trust, which is actively seeking solutions to the challenge of affordable housing for Māori in the North.

The relationship could give Rueben the opportunity to showcase two whare uku designs on trust land in Kaitaia, so that whānau can see the final product for themselves.

The couple have taken a holistic approach to the project, from considering the history and previous use of the land to seeking kaumātua advice on the positioning of their new whare.

With the Ara Wairua passing over the couple’s land just before it reaches Te Oneroa-a-Tōhē (90 Mile Beach) on its way up to Te Rerenga Wairua (Cape Reinga), the exact positioning of the whare was a big issue. As Heeni half-jokingly says, she didn’t want to build where she would hear “whoosh, whoosh, whoosh” going past her in the middle of the night.

“So yeah, we took the Ara Wairua into account, as well as the location of the family urupā. We chose a site that is secure and sheltered, and built up high above the flats; safe from possible floods but close enough to a water source.”

Tikanga is also an intrinsic part of the build. “We followed the Maramataka (the Māori lunar calendar) while building the house so we could maximise output on optimum days, and just as importantly, it told us when it was best to rest and not stress if things weren’t running smoothly.” says Rueben.

Balancing tikanga with the project management and meeting deadlines was sometimes a challenge, but they were determined to follow their principles. Despite the heavy demands involved with project-managing the build and a hands-on approach to the construction, Rueben also has plans for widespread horticulture on the flats below the whare uku, including peruperu (Māori potato), a crop that has seen him travel internationally to share his knowledge.

“We recently had the opportunity to visit Samoa and saw how the Samoans still really treasure the land. It was wonderful to see. They are working it every day – their hands are in the soil and the land is feeding their families; whereas over here, a lot of Māori have lost that connection with the land.

“The whenua is very important to us physically, spiritually and culturally. It has sustained my whānau and hapū for over 20 generations and it is our responsibility to nurture that connection within our next generation.”

Rueben’s commitment to working the land extends beyond growing crops for his wider family: he also runs regular courses for locals interested in growing food for their whānau.

It is that connection to and love of the land than has seen Heeni and Rueben start planning the development of a papa kāinga that will ultimately consist of three homes and a communal building – all featuring rammed earth walls.

The groundswell of support within the wider hapū suggests that whare uku dwellings have the potential to play a realistic role in the path towards tino rangatiratanga in the North.

“The build is bringing people together with a common goal. If a machine breaks down for instance, we have access to mechanics straight away, because they support the kaupapa.”