Fortune favours the brave

Oct 6, 2015

Nā Rob Tipa

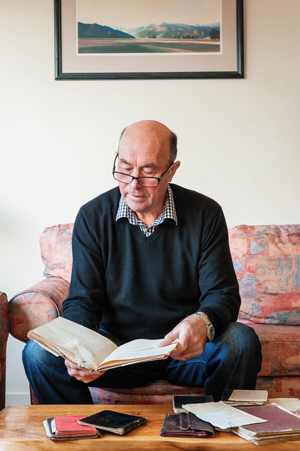

Edward Ellison with one of his great-grandfather’s diaries.

Kimi Ākau (the Shotover River) holds a special place in the hearts of the Ellison whānau, thanks to the courage of one of their tupuna, who virtually made his fortune on this wild high country river in a single day.

The year was 1862, and the lucky man was Raniera Tāheke Ellison, who was drawn to Otago by first reports of the discovery of payable gold at Gabriel’s Gully on the outskirts of Lawrence in 1861.

Ellison was born at Korohiwa on the Wellington coast near Porirua in 1839, the son of an English whaler, Tom Ellison, who drowned in Titahi Bay not long after Raniera was born. His mother, Te Ikaraua, had whakapapa connections to Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Mutunga and Te Atiawa.

Edward Ellison, a kaumātua of the Ōtākou Rūnanga on Otago Peninsula, is a direct descendant of Raniera Ellison, and still has in his safe-keeping his great-grandfather’s personal diaries, neatly hand-written in te reo Māori.

The diaries are an extraordinary first-hand account of Raniera’s travels throughout New Zealand, including a detailed record of his fabulous discovery of 300 ounces of gold in one day at Māori Point on the Shotover River. This golden day effectively set him up for life.

Edward picks up the story from his great-grandfather’s diaries:

Raniera was about 22 when he arrived in Otago in September 1861, and gravitated towards the kaik at Ōtākou, where he had tribal links with his Te Ātiawa iwi.

Initially he worked as a coxswain on the pilot boat on Otago Harbour, until he and a few others from Ōtākou joined the rush to the diggings near Waitahuna. He had no luck there so decamped, sold his shares and moved up into the hills near Waipori, where he found a few ounces of gold, but not enough to encourage him to stay.

He returned to Ōtākou and presumably continued working as a coxswain on the pilot boat, until he heard of new strikes on the Dunstan field, near Alexandra.

A party from Ōtākou travelled north to pick up three people from Moeraki and came back to Waikouaiti to collect more people to join their party. Edward says they met up at Lake Taieri (near Hyde) and went on to the Dunstan field from there.

By the time they got to the Earnscleugh goldfield (near Alexandra) all the claims had been taken, so they headed upstream on the Mata-Au (Clutha River) to Cromwell. They were about to return to Alexandra when they heard of new strikes near Whakatipu Wai-Māori (Lake Whakatipu).

They crossed the Mata-Au near Cromwell, continued up the true left side of the Kawarau River, and climbed over a mountain range to descend to a new claim, known at that time as Foxes (now Arrowtown).

On the way, they met a party of Ngāi Tahu from Southland led by a man by the name of Rickus. In his diary, Raniera noted the southern group were lucky to have horses, but the Otago party were fit from their walk from the coast, so it was no hardship for them to continue on foot.

The group then made their way to a place now known as Māori Point, between Arthur’s Point and Skippers Canyon.

The river was in full flood and none of the party was game to cross, so there were no miners on the true right bank, or western side of the river.

“When Raniera looked at the river he said it was swift, it was deep, and it was rocky, so it probably wasn’t a good idea to attempt to swim it,” Edward says. “On the whole, he said the group had had a bad run of luck, so they were determined to give it a go.”

In his diary, Raniera referred to an earlier incident when a storm overtook the pilot boat, and all were tossed into the sea. One by one he rescued all of the crew and returned safely to Otago Heads. So he was undoubtedly a strong, confident swimmer.

They returned to camp and early the next morning, Raniera swam the Shotover and caught a few weka on the western side, so he was popular when he returned to camp with fresh food.

The following morning Raniera and Hakaraia Haereroa decided to cross the river again, before anyone else was up. Both safely crossed the swift-flowing river, but a dog that followed them was swept downstream and became stranded on a ledge on a rocky point.

Raniera swam downstream to rescue his dog and, legend has it, he noticed flecks of gold in the dog’s coat. He then recovered 300 ounces of gold in the rock crevices before night-fall.

It was a fabulous change of fortune for this lucky pair, and it was two days before other members of their party joined them. In those days, 300 ounces would have been worth about 1000 pounds, a small fortune at the time. In today’s terms, that much gold would fetch close to $530,000.

Edward says the pair, and a third man (possibly Henare Patukopa), probably only worked their claim for a matter of weeks; because in April 1863, records show they sold their 40 x 20 ft Māori Point claim to a group of Welshmen for 800 pounds. Again, this was a small fortune at that time.

Raniera was now a man of means, and his good fortune on Kimi Ākau undoubtedly set him up for life.

He returned to Ōtākou and by August of 1863 he had married Nāni Weller, grand-daughter of the influential Ōtākou chief Te Matenga Taiaroa.

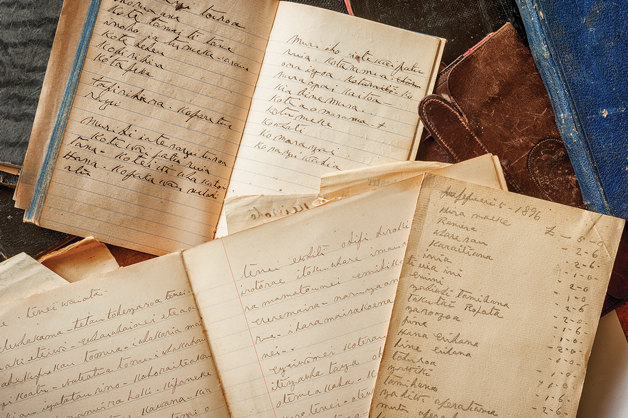

Detail from the diaries of Raniera Ellison.

Ellison whānau history records that the old chief raised Nāni after her mother, Nikuru, died in childbirth. He fed her on the juice of the tuaki (cockles) until a wet nurse was brought over from Karitane. In turn, Nāni looked after Taiaroa in his later years.

The memory of fierce battles between Te Rauparaha and Ngāi Tahu were still very fresh in the memories of tribal elders at Ōtākou, so it is hardly surprising Raniera, with his Te Ātiawa connections, was not deemed to be a suitable suitor.

“Clearly it wasn’t an agreed marriage between Nāni and Raniera, so they eloped and were married at First Church in Dunedin,” Edward says. “He may have been courting her for a while, but I don’t know.

“I suspect Taiaroa was alive when they were courting, but he wasn’t alive when they eloped in August, 1863. He died in May of that year,” Edward says.

When Raniera and Nāni’s marriage was discovered by her whānau, legend has it she called out to them: “Tūreiti, tūreiti (too late, too late).”

Between them, Raniera inherited land at Waikanae and Nāni inherited land from her grandfather at Ōtākou and Puketeraki.

“They may never have been able to farm it if they did not have the capital,” Edward says. “Clearly he had capital because he set up three farms, had houses in all those places, and travelled a lot between them.”

Over the next 20 odd years between 1864 and 1886 Raniera and Nāni had 12 children, generally split between the three farms they were moving between and developing.

Their eldest son Matapura initially worked the Waikanae property, and later the family farm at Karitane.

Tom Ellison trained as a lawyer and made a name for himself as a famous All Black, Edward Pohau Ellison trained as a doctor, and Raniera married into the Ngāti Kahungunu iwi and was involved in tribal affairs in that region.

Edward’s grandfather married locally and stayed on the Ōtākou farm.

Tāua Nāni and Pōua Raniera also raised many of their mokopuna in their Ōtākou homestead, Te Waipounamu.

Raniera maintained his strong northern iwi affiliations to Taranaki and Parihaka in particular. He was related to Te Whiti, supported the cause for Māori land rights, and was also politically active in support of the Te Kotahitanga movement’s bid to set up a national Māori Parliament.

“He had the means to travel, and he did,” Edward says. “Within the community here he was respected and revered as one of their leaders really, even though he wasn’t Ngāi Tahu.”

He was known locally as the man with the feather in his hat, probably swan feathers, several of which have been well preserved between the pages of his hand-written diaries.

“He had a very strong social conscience I believe. He was very active politically and strong around Māori issues, particularly over land loss and Māori achieving their place in the New World.

“He was obviously close to the Kīngitanga movement as well, because King Tawhiao gave him a tokotoko, which is still in the family’s possession.

“I think he was to a degree entrepreneurial, and obviously he had a good business head on him. It was a great foundation for the Ellison family, because he obviously managed his affairs well.”

The Ōtākou farm has given the family a strong financial base for several generations. During the Second World War three brothers – Edward’s father George, Uncle Rani, and Uncle Rangi – all owned and ran the farm.

Edward still has Raniera’s stock books from his Waikanae farm, and still farms the Ellison family land at Ōtākou.

His Uncle Rani founded Ōtākou Fisheries, using the farm partly as collateral, and ran it as a co-operative which employed family, who had the option of working for wages or taking up shares in the company.

“Much of Rani’s business success was built on his personality,” Edward recalls. “It ended up as an extended whānau business with over 50 boats fishing from Timaru to Milford Sound, and exporting to Australia and the United States.”

The Ellison family retains a strong connection to Kimi Ākau through family holidays, and a party who attended the family reunion in 1985 visited Māori Point.

As part of the Ngāi Tahu Settlement a reserve was created at Māori Point and administered by the Department of Conservation. Interpretative panels record the story of Raniera and other Māori miners who made their fortunes there.