GMO

Jun 29, 2021

In 2016, TE KARAKA published Environmental Watchdogs, an article about the crucial but largely unseen work of the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms (HSNO) Komiti. Five years later, and with the renewed threat of GMO on the horizon, we return to the topic as the komiti calls on Ngāi Tahu whānui to make sure their voice is heard, writes Anna Brankin.

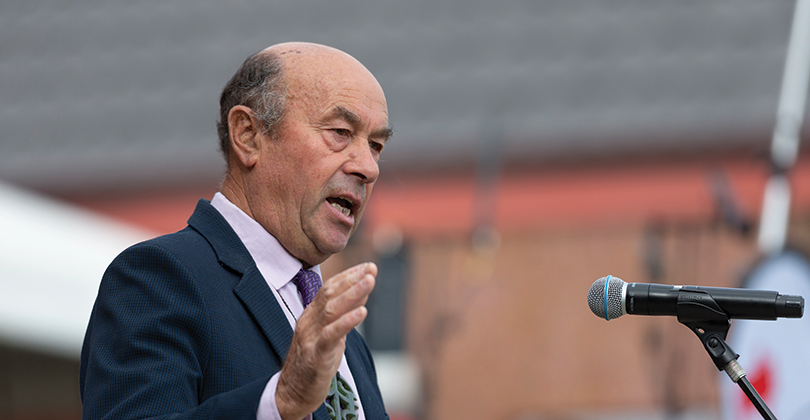

“Back in the 90s you only had to mention gmo at hui-ā-tau and people would be on their feet because that was the passion that was around at the time,” says komiti chair Edward Ellison (Ngāi Tahu – Ōtākou). “Most of our people back then immediately saw the potential impact of genetically-modified organisms on our rangatiratanga, kaitiakitanga, on our taonga species and our whakapapa.”

These days, Edward says the komiti struggles to get anywhere near the same level of engagement from the iwi – but this does not mean risk is no longer there. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu established the HSNO Komiti in 2003, in the wake of national controversy surrounding GMOs that led to the passing of the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 and the Royal Commission on Gene Modification in 2001.

The iwi made a submission opposing GMO to the Royal Commission, whose report ultimately led to strict regulation of the import, development, testing and release of GMOs in Aotearoa. These activities must be approved by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA). The HSNO Komiti was created to work with the EPA on behalf of the iwi, drawing on mātauranga Māori to influence its decision-making. As the-then Deputy Kaiwhakahaere with an existing environmental portfolio, Edward was the natural choice as chair.

“We principally work with the Environmental Protection Agency on behalf of Te Rūnanga, to engage on applications for the import of hazardous substances and new organisms,” Edward explains. “We make submissions and attend hearings, we put pressure on the EPA to ensure that they notify us of all applications.”

Edward describes the work of the komiti in terms of trying to foresee and prevent “unintended consequences”. He uses the example of rabbits being introduced to New Zealand in the 1830s to provide game for British settlers. Less than 40 years later, their numbers reached plague proportions and they were recognised as an ecological threat. The solution? The introduction of ferrets, weasels and stoats to control the rabbit population – leading to the predation of our native bird species.

[Mātauranga Māori is] the framework of our worldview, of te ao Māori, that truly explains the function and responsibilities of the HSNO Komiti. The Western scientific approach is more reductive, and considers only the specific and minute molecular details of a product. It’s mātauranga Māori that looks at the interconnectedness and how one thing will affect another.”

Edward Ellison HSNO Komiti chair

“What we do now is different, in that it is very technical in detail and a wee bit intangible,” says Edward. “The point of it is to have a komiti who are familiar with these unintended consequences, so they can identify cultural elements that might be at risk.”

Today the komiti consists of Dr Emma Wyeth, Dr Benita Wakefield, Stephanie Dijkstra, Kyle Davis, Nicholas Denniston and Gail Gordon, bringing together a wealth of technical knowledge, scientific expertise and mātauranga Māori.

As one of the newer members, Stephanie (Ngāi Tahu – Ōraka Aparima) says it is a privilege to be part of the team, and acknowledges the immense progress that has already been made.

“Edward has been an amazing rangatira of this komiti, as well as [former member] Oliver Sutherland and Dr Emma Wyeth,” says Stephanie. “They’re the ones who have done the hard work to get us to where we are and continue to be a driving force for future changes.”

Stephanie joined the komiti in 2018 after completing Aoraki Bound and searching for other ways she could connect and contribute to the iwi. There was a vacancy on the HSNO Komiti and, with her background in plant cell biology, she immediately saw it as a way

she could give back.

“It fits in perfectly in terms of my aspiration to see mātauranga Māori more widely accepted by the scientific community,” Stephanie says. “One of the things that came out of my thesis and the discovery of my Ngāi Tahutanga was a sense of activism – wanting scientists to understand what it means to work within Te Tiriti and that it’s not a detriment. Having access to mātauranga and a dataset that is hundreds of years old is only a value-add.”

This sense of activism is shared by Edward, who first became involved in environmental advocacy in response to proposals in the 1970s to build an aluminum smelter at Aramoana or Ōkia Flats in Ōtākou. “We got active on it and ultimately the proposals were blocked, and then along came the Conservation Act and the RMA.

I just gravitated into the environmental space and I’ve been there ever since,” he says.

Although it largely goes unseen, the work of the HSNO Komiti has been significant in terms of preventing further degradation to our waterways and whenua. “It’s a fulfilment of our role as kaitiaki, and of the EPA’s obligation to consult with us as a Treaty partner. We can determine what chemicals are coming into the country, and look for opportunities to remove older and more toxic chemicals as well,” Stephanie says. “I see us as the gatekeepers. When you look at all the other conservation boards and committees, we are the first stop – we can try and stop the substances coming in in the first place, that then cause the harm that makes it necessary to have taonga species and environmental recovery boards further down the line.”

Although it largely goes unseen, the work of the HSNO Komiti has been significant in terms of preventing further degradation to our waterways and whenua. “It’s a fulfilment of our role as kaitiaki, and of the EPA’s obligation to consult with us as a Treaty partner. We can determine what chemicals are coming into the country, and look for opportunities to remove older and more toxic chemicals as well,” Stephanie says. “I see us as the gatekeepers. When you look at all the other conservation boards and committees, we are the first stop – we can try and stop the substances coming in in the first place, that then cause the harm that makes it necessary to have taonga species and environmental recovery boards further down the line.”

Through the years, the komiti has had many successes in hearings, from small wins in placing specific controls over the import of certain chemicals, or bigger issues such as blocking a chemical from the country altogether. But Edward and Stephanie agree its most important work is helping improve the cultural competency and mātauranga Māori of the EPA.

“When we talk about mātauranga Māori, it takes us right back to the creation traditions and our various ātua. It’s the framework of our worldview, of te ao Māori, that truly explains the function and responsibilities of the HSNO Komiti,” says Edward. “The Western scientific approach is more reductive, and considers only the specific and minute molecular details of a product. It’s mātauranga Māori that looks at the interconnectedness and how one thing will affect another.”

Stephanie agrees, saying the EPA and several companies they encounter are starting to change their attitudes, realising that it’s better to consult with iwi early rather than risk their application being denied at a hearing. “Bayer Agrichemical is an example of an organisation that has started coming to us six months to a year before they’ve even put in their application. That means before they even apply they have often accepted mitigation measures that we would be happy with,” Stephanie says. “Sometimes we will still oppose something if the environmental cost is too high, but it’s really gratifying to see them start to consider things like effects on taonga species, (and) effects on juvenile fish.”

One of the things that came out of my thesis and the discovery of my Ngāi Tahutanga was a sense of activism – wanting scientists to understand what it means to work within Te Tiriti and that it’s not a detriment. Having access to mātauranga and a dataset that is hundreds of years old is only a value-add.”

Stephanie Dijkstra Hazardous Substances and New Organisms (HSNO) Komiti member

Thanks to New Zealand’s stringent GMO policy, the komiti mostly finds itself operating in the hazardous substances field. But with changes on the horizon, it believes it is time to revisit the tribe’s stance on GMO – and it needs our help.

“There are a couple of GMO issues on the back burner at the moment, and we really want to hear from mātauranga holders from within our iwi, who have any knowledge relevant to these issues,” says Stephanie. “GMO was the reason our komiti was founded in the first place, but attitudes and technologies have evolved so our existing policy can’t really be applied to the issues we’re dealing with now.”

The komiti expects GMO to re-enter the national conversation on several fronts, particularly in conservation and medicine. Gene editing is a potential approach for pest control, and one Edward believes will be considered in light of New Zealand’s Predator Free 2050 aspiration.

Essentially, this approach would use a gene-drive to target the viability and/or fertility of a pest species, thereby reducing its population over time.

Meanwhile, medical researchers continue to explore xenotransplantation – procedures that involve the transplantation of animal cells, tissue or organs into humans. While there are obvious health benefits, historically Māori have been hesitant around the tikanga of this approach.

Gene editing and xenotransplantation are still strictly regulated by the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, but Edward urges Ngāi Tahu whānui to prepare a stance.

“We should be arming ourselves with information and knowledge now, in this window where we’re not immediately threatened by the prospect of GMO coming into the country,” he says. “That way when it does start to get some momentum we’re not running, we’re in front and influential.”

The HSNO Komiti will be presenting at Hui-ā-Iwi and want to hear from Ngāi Tahu whānui about their views on GMO. You can get in touch by emailing [email protected].