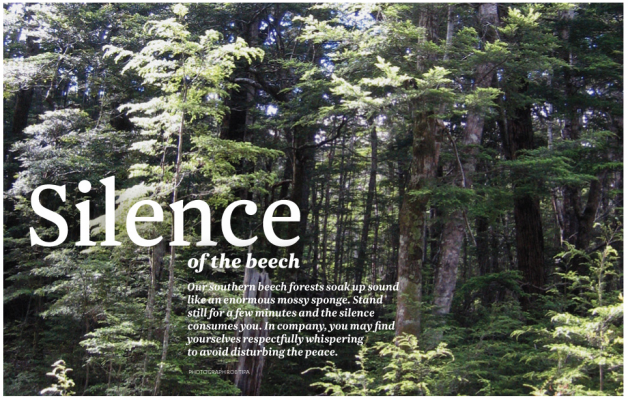

He Aitaka a TāneSilence of the beech

Apr 5, 2012

Beech forests are widespread over much of Aotearoa. They straddle the spine of the mountain ranges of both islands, from the volcanic plateau of Te Ika a Māui to the southern coasts and ranges of Murihiku.

They grow in dense stands of large straight-stemmed trees up to 30 metres tall, in forests often notable for their open forest floor and sparse undergrowth – a sharp contrast to coastal podocarp forests.

Māori recognised three different species of beech by name: tawai or tawhai for silver beech, tawhairaunui (large leaved) for both red beech and hard beech, and tawhairauriki (small leaved) for black beech and mountain beech.

Yet surprisingly, there is little written record of our tūpuna foraging in the extensive beech forests of Te Waipounamu the same way they harvested resources from coastal podocarp forests and wetlands.

There was an obvious reason for that. Beech forests do not bear fruit that attract native birds in the same numbers as lowland forests. They were comparatively barren in terms of food and plant resources for Māori, which explains the eerie silence of these alpine forests.

But there was one notable exception, and we have Herries Beattie’s Traditional Lifeways of the Southern Māori to thank for preserving the story of an annual harvest of kiore-māori or kiore-tawai (native rat) from the beech forest.

According to Beattie’s sources, kiore-māori were bigger than the ship rats that arrived with the first European sailing vessels to land on these shores. They were “fatter, better looking, lighter grey in colour with a shorter ihu (nose) and shorter waero (tail)”.

His contacts told him kiore were more common in Te Waipounamu than in the north, never came near pā or kāinga and always kept to the bush, well away from humans. They were clean animals that fed on the fruit, berries and seeds of mataī, kahika (kahikatea), tawai and other native trees.

Kiore were migratory and moved en masse from one locality to another as fruit and seeds ripened at different stages of the season.

Beattie’s contacts described how migrating kiore crossed rivers by linking themselves teeth-to-tail in a live chain that used the current to carry them across fast or flooded rivers to the far bank, effectively creating a bridge for others to run across their backs.

If the chain broke many drowned, but the principle has since been adopted by generations of Māori and Pākehā travellers who link arms, the strong supporting the weak, to cross fast-moving high country streams and rivers.

In season from April to May or June, kiore grew fat on tawai seed on the forest floor. Reliable sources told Beattie how hapū from Canterbury ventured to Tawera (Mt Oxford) and into the backcountry to trap them by the thousands.

Kiore were caught one at a time at night in a tāwhiti (trap) set on their defined bush tracks, using a whana (bent stick) and karu māhaka (noose). Each trapper could catch 400–500 kiore in a season.

“The trapping was a particular and careful work as traps were set all over likely spots and by the time a man got to the end of them on a trip and reset them they were full again, so he set them again and again,” Beattie wrote.

The kiore were singed, their fur rubbed off, gutted, cleaned, cooked and preserved in a pōhākiore (kelp bag) in a similar manner to tītī, weka and tūī, to provide food reserves for winter.

Beattie says kiore were a tasty delicacy for Māori and Pākehā alike. A group of whalers who took refuge at Tokanui were so short of food they had to eat kiore to survive, and said “they had never tasted anything better”.

Back to the forest: beeches are an ancient species dating back 135 million years to the great continent of Gondwanaland. New Zealand has four species that grow from sea level up to 1200 metres.

Each is distinguishable by the size, shape and teeth or absence of teeth on its leaves. The timber also has its own special attributes of durability, hardness and colour, and special uses according to its species, elevation and growing conditions.

Europeans originally called them birches, but later corrected that to beeches. In fact they are not the same species as European beeches at all. Their Latin name Nothofagus means “false beech”.

Generally their timber is regarded as a durable hardwood. North Island-grown beech is regarded as stronger because of its greater density. South Island beech is highly prized for its woodworking qualities.

In the early days of European settlement, beech was widely used for wharf, bridge, railway and house construction. These days it is more highly valued for fine furniture, joinery, woodturning, decorative floors and other specialist uses.

Some sources say native beech was largely ignored because of the variable quality of its timber, so loggers turned their attention to the more valuable species such as rimu, tōtara and kahikatea.

There is little specific evidence of Māori using tawhai for its timber, apart from a pā (jigger) or lure to catch mangā (barracouta). A chip of tawhai was hard enough to withstand the high-speed attack of mangā and many were caught when their teeth lodged in the wood, rather than being caught with a hook.

The bark of silver and black beech was used to produce a black dye for staining harakeke (flax) and tī kōuka (cabbage tree) fibre. One of Beattie’s reliable informants also described a process of using the dust of rotten tawai mixed with water and oil from either tītī or fish to produce a blue dye he called pukepito.

The bark also contains tannins that were used by early settlers to tan leather.

There is little written reference of Māori using any part of the tawhai for medicinal purposes, which seems unusual.

These days the closest most of us get to harvesting resources from a beech forest is warming ourselves around a hot, clean-burning fire in the mountains on a cold evening.