Ka hao te Rakatahi Wai ora – we need to do better!

Oct 5, 2017

Nā Nuku Tau

In light of the 20th anniversary of the Settlement of the Ngāi Tahu claim, I thought it relevant to write on another issue Ngāi Tahu faces in terms of rights and property – water. Water is the most precious resource on Earth, and I think everyone can agree we don’t value it to the extent we should. Recently I was asked to give a speech to Environment Canterbury (ECAN) workers and answer questions on a panel. The following is the speech I gave on rivers and the issues with our current legislation around water.

In light of the 20th anniversary of the Settlement of the Ngāi Tahu claim, I thought it relevant to write on another issue Ngāi Tahu faces in terms of rights and property – water. Water is the most precious resource on Earth, and I think everyone can agree we don’t value it to the extent we should. Recently I was asked to give a speech to Environment Canterbury (ECAN) workers and answer questions on a panel. The following is the speech I gave on rivers and the issues with our current legislation around water.

When I was asked to give a three-minute speech on water, I had no idea what to discuss or say. If I’m to be speaking to ECAN reps, what’s the point of giving facts and figures when I’m either talking to someone who wrote them, or knows them because it’s part of their job to know them?

I don’t think anyone really wants a high schooler to take the stage and regurgitate knowledge to more well-informed people. So I decided to go with some good old-fashioned anecdotal evidence – stories passed down.

Anecdotal evidence is widely considered to be logical fallacy. However, I felt it was the best thing I could bring to the table. As a boy who has grown up in Tuahiwi and explored many parts of Canterbury in the pursuit of mahinga kai, I do have some, admittedly limited, experience.

My first story is one given to me by my pōua Rik Tau. Anyone who knew him would know that like many grandfathers, he certainly wasn’t above adding a little GST to his stories, especially around fish. However, this is one I’ve heard from many elders around the pā.

As a child, he would go down to the Ashley and with a stick herd shoals of whitebait into a net. There was always enough and it was easily caught. This process took minutes and the whole extended family could easily be fed.

Maybe there weren’t shoals and maybe it wasn’t as quick as stated, but when I talk to anyone of the older generation about whitebaiting, they say the same thing: there was certainly far, far more.

Fast-forward to today and there is still whitebait in the Ashley, and there are still people to catch it. However, there are days when all you leave the river with is an empty net, sunburn, and an extreme sense of Kiwi shame. There is also the lingering scent of cow faeces in your nostrils as the Ashley River reeks of it on sunny days. My pōua Noel says the river is slowly choking.

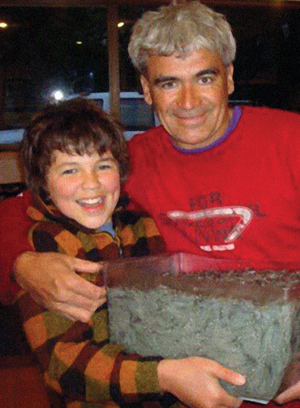

Nuku (aged about 10) with his Uncle Maru happy with their catch.

I remember when I was 10 we took two boys home for a bath because they smelt so bad. When I asked them why, they explained that when they stick their heads in the net, the water is mixed with cow faeces and it dried in their hair. To them this was natural. I consider it anything but. Reeking of cow shit should not be a regular part of whitebaiting with your family.

The Crown says no one owns water, so if they don’t own it, surely they don’t have the right to allocate water through the Resource Management Act? I agree the Crown doesn’t own the water, because under the 1848 Canterbury Purchase it was never sold.

In my view this vagueness around assumed rights is the reason why we are failing in how we properly deal with water. Pollutants from intensive farming and storm water in towns are hitting irreversible highs. It’s the tragedy of the commons – no one takes responsibility for property held in common. We take water for granted, and our collective in-action means my generation inherits a mess.

On our muttonbird island Pohowaitai, everyone conserves water because we all depend on the water we get off the roof. No one wastes it.

We need a system that makes people pay for use and pay dearly for abuse and wastage. No corporate body should ever own water, and the granting of consents should be weighted on public versus private use.

A foreign water bottling firm in Belfast can pump 4.32 million litres a day, roughly equivalent to the water usage of the city’s biggest suburb, Riccarton. The firm will likely pay nothing or very little for their use of this precious, pure, and globally-prized resource. Will the bottles they use be biodegradable, or will they also end up in the great Pacific Ocean garbage patch?

This is still everyone’s problem, regardless of who you are. I have often seen people fish the banned spawning grounds at the Ashley with no regard for tomorrow.

My main message is that we all need to do better. We all need to become water warriors. I like to whitebait. I like lying in the grass with a book and my headphones, or watching the sun rise on the banks. I like the idea of catching my own food and eating it that day. It’s an experience I want my kids to have, just like my ancestors had before me. The Ashley, Lake Ellesmere, and all the other water bodies of New Zealand are precious taonga and we all need to treat them that way. Nothing exists without water. There is arguably nothing more important than water on the planet. We can all do better.

Eighteen-year-old Nuku Tau (Ngāi Tahu, Te Ngāi Tūāhuriri) is a Year 13 student at Christ’s College.