KaiReviving the old ways

Oct 8, 2012

Spend time in the cookhouse and you will learn not just about mahinga kai, but also about your whakapapa. Karl Russell shares early memories of Arowhenua and his future ambition to develop modern kai karts. Kaituhituhi Adrienne Rewi reports.

Photographs Adrienne Rewi.

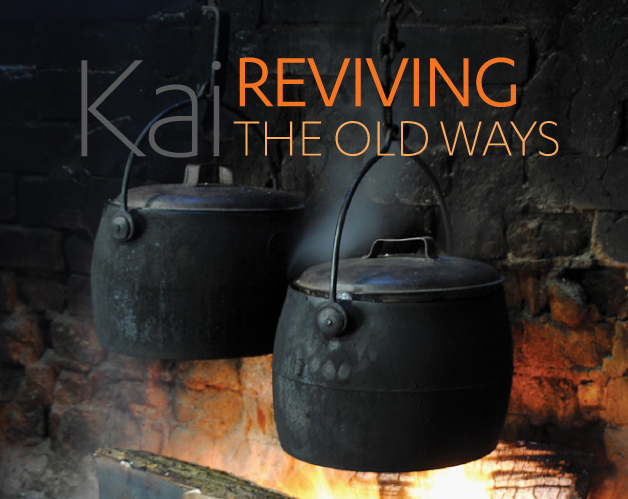

It’s quiet and dimly lit in the cookhouse at Arowhenua Marae. Karl Russell peels potatoes for beef stew. He’s happy in his domain. His favourite cast iron pots hang over a fire. Occasionally he breaks the silence with snippets of the whānau histories that collide in this historic 112-year-old cookhouse. It’s one of the last working kāuta left in the Ngāi Tahu rohe.

Karl (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa/Ngāti Ruahikihiki, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha), is part of a long tradition. He’s the marae cook – just like his father, George Te Kite Iwi Russell, before him. When he was five, he learned to cook in the kāuta under his father’s watchful eye. He’s now 56 and proud to be part of a small team bringing the kāuta “back to life”.

Karl (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa/Ngāti Ruahikihiki, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha), is part of a long tradition. He’s the marae cook – just like his father, George Te Kite Iwi Russell, before him. When he was five, he learned to cook in the kāuta under his father’s watchful eye. He’s now 56 and proud to be part of a small team bringing the kāuta “back to life”.

“For me it’s like home. It’s about being with my tīpuna, especially my father and uncles. A lot of my whānau have cooked here and I always think of them when I’m cooking.

“I can sit here for hours talking about the history of the kāuta. I always say you’ll learn more about your whakapapa in here after a tangi than anywhere else.”

When Arowhenua Marae built its new kitchen and wharekai in 1986, many things changed at the marae, especially for the men, says Karl. There was talk of pulling the corrugated iron kāuta down but due to cries of protest, it was retained.

“This place represents a unique slice of history. It’s a museum piece; it is Arowhenua. It’s iconic to us. It’s the focal point for tangi and hui and even if we don’t cook in here, we’ll have the fire going. It would have a profound effect on all of us if it wasn’t here.”

The kāuta, originally sited across the road from the marae, was moved to one side of the wharenui in 1905. It had a dirt floor up to 1956, and until about 25 years ago, it was solely the men’s domain. Today it is a short walk around the back of the wharenui from the new kitchen.

As Karl stirs his simmering beef and kidney stew, he talks about the early days when up to 20 men would be working in the kāuta preparing for a tangi. He says when the karanga went out with news of someone’s passing, people at the pā packed their black pots, dishes and spare kai and crews would “do the rounds” with the horse and cart, picking up the cooking supplies. The wharenui would be prepared for guests and the cooking organised.

“Everyone had a role then. No matter how small, they were an essential link in the marae process and those skills were passed down through families.

“We’d have up to 30 cast iron pots in action, some of them being kept warm with hot coals. We’d do an umu kaha (the local name for a hāngī); and we’d have plum duffs cooking in two coppers. No one ever goes away from here hungry and the food cooked in the iron pots has a deep, rich, often smoky flavour that you don’t get with new stainless steel pots.”

Beyond the kāuta, Karl’s life has always revolved around the practice of mahinga kai. As one of 13 children, he spent his days hunting and gathering.

Beyond the kāuta, Karl’s life has always revolved around the practice of mahinga kai. As one of 13 children, he spent his days hunting and gathering.

He says back in the 50s and 60s, most of their kai was from the land.

“It’s how we survived. We lived off tuna, kanakana, whitebait, pātiki, watercress and kaimoana. We caught trout and salmon in the lagoons and rivers. We collected swans’ eggs and seagull eggs for baking. We dried karengo and traded it for tītī and other foods.

“We gathered according to the seasons and we lived like kings. I still trade kai. If you get an abundance, you share.”

Karl is working on reviving those old ways on several fronts. He’s encouraging young men back into the kāuta during big marae events and teaching them the old ways; and with his younger brother and chef, Jason Russell, (one of eight whānau chefs), he’s developing unique contemporary recipes based on traditional kai.

“My dream is to have upmarket Kai Karts that travel to food festivals delivering our kai at a fine food level,” Karl says.

He’s also developing kai-based displays for the Ngāi Tahu Hui-ā-Iwi, which is being held at the Lincoln Events Centre in November including demonstrations on how to make rēwena bread, fried bread and plum duffs. There will be a kaimoana hāngī, demonstrations on tuna processing, and cooking. Much of that information is also being used for the collation of a traditional kai recipe book, which Karl hopes to release to coincide with Te Matatini 2015. He’s also planning two-day mahinga kai workshops at Arowhenua.

“We’ll go out early on a Saturday and catch tuna and gather kaimoana and then we’ll spend the weekend cooking. I want to see a sharing of traditional knowledge.

“Mahinga kai is at the basis of who we are as a people and food is certainly my passion. I believe the sweetness we have in our food comes down to the wairua we put into it and our kids will learn much about their whakapapa if they learn about mahinga kai.”

Beef & kidney stew

A hearty stew is one of Karl’s old favourites and he varies his recipe depending on ingredients available. This basic recipe, similar to the popular ‘boil-up,’ can be prepared as a casserole, in a pot, or in a slow-cooker.

A hearty stew is one of Karl’s old favourites and he varies his recipe depending on ingredients available. This basic recipe, similar to the popular ‘boil-up,’ can be prepared as a casserole, in a pot, or in a slow-cooker.

Method

Dice stewing beef and kidneys, or your preferred choice of meat, and place in hot water with salt. Cook slowly for about an hour, or until the meat is tender.

Add your preferred chopped vegetables – carrots, potatoes, kūmara, pumpkin, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli – and cook for another 20 minutes.

Thicken with a small amount of cornflour and eat with fresh rēwena bread, fried bread, or bread of your choice. It can also be served with rice.