Karanga

Jul 17, 2012

Nau mai, haere mai

Ki tō tātou marae e

Haere mā rā….

Mereana Moki Kiwa Hutchen (Aunty Kiwa) believes in what she calls “a user-friendly” approach to karanga – in being welcoming and down-to-earth.

“I like to use a simple karanga for a pōwhiri, one that will welcome all iwi. You can add to that, depending on the occasion, to make it deeper and more picturesque but as kaikaranga you should always be mindful of people waiting. It is not about telling a whole story. You can be very colourful and embellish things a lot but you need to be true to the event and not get too carried away. You need to keep it real.”

Aunty Kiwa (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau-a-Apanui), 79, was picked to learn to karanga because of her whakapapa.

“In my case, it was about who my grandmother was. People looked to her for help and guidance. It always comes back to genealogy and the eldest daughter was usually the chosen one, but only if she was interested and able to work alongside the elders. Not everyone wants to karanga. My elder sister was terrified. She didn’t want to do it, so the responsibility was passed down to me.”

A good karanga matches the occasion, she says. And a good kaikaranga chooses her words carefully and never drowns out the other caller.

“We call that kaihorohoro – gobbling words. It’s very bad practice. Karanga should not be a power game. A good kaikaranga has a way about her, a charisma. She’s special and she has heart.”

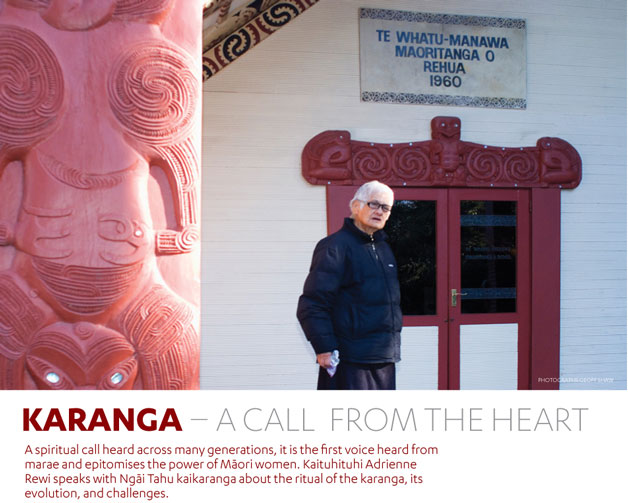

But the protocol of karanga is facing challenges as it evolves in modern life. Traditionally viewed as a connection between the living and spiritual worlds, the karanga is steeped in tikanga and epitomises the mana wahine — the power of women within the marae. It is a spiritual call that has been heard through generations of whānau across the country.

In most cases the karanga includes a welcome to a particular marae, both to the living manuhiri and to the spirits of the dead. The kaikaranga from the host marae starts proceedings by piercing the air with her call, delivering her greeting to those who have passed on, and the living, on one held breath.

Kaikaranga from the visiting group – the kaiwhakautu – return the karanga on behalf of the manuhiri. Each group honours the other, weaving a continuous “spiritual rope” that “pulls” the manuhiri onto the marae.

In Invercargill, Peggy Peek (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha), 76, is concerned that karanga – “one of the last rituals steeped in tikanga we have left” – is being altered, almost to the point of being abused. A younger generation has an anything-goes attitude, she says. They karanga wearing jeans or bright colours, instead of the traditional black skirts. Peggy is fearful the art is dying out.

“We need to bring young women onto the marae and train them. We don’t have the luxury of apprenticeship in the traditional sense, because whānau are often fractured as young ones move away to follow employment.”

Peggy says she was taught to karanga by the nannies, who pushed her out front at different events when they felt she was ready. Peggy has been kaikaranga at Murihiku Marae since 1990. She is also an ordained Anglican priest, and says the two roles often support and enhance each other. Empathy and compassion are key to both; and while she is keen for young women to train as kaikaranga, she believes the role does call for a certain level of maturity, confidence and life experience.

“Some young ones want to be out front doing the karanga but they don’t want to wash the dishes. They don’t want to put in the long hours to learn and appreciate the depth of the role.

“In 1983 when we opened our new wharenui at Murihiku, we all sat down and realised we had to learn the tikanga that would support it. I started learning te reo. That does affect your karanga and your ability to perform it well.”

Maruhaeremuri (Kui) Stirling

For Maruhaeremuri (Kui) Stirling, (Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau a Maruhaeremuri/Apanui, Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāi Tahu), of Tuahiwi Marae, the role of kaikaranga was traditionally about status according to whakapapa.

“I was one of the few children taken to the marae. In those days the hapū had roles for each and every waānau and those roles were sacrosanct. The role of speaking on the paepae and the role of kaikaranga were both senior positions that were passed down through families; each generation taught the next and your whakapapa placed you in the order of things. It’s different today. It’s whoever puts their hand up to fulfil the role,” she says.

“I’d heard the sounds of karanga all the years of my life but when I was young I hoped I might avoid it because it’s such a big responsibility. When I was 20 and living in Christchurch, Aunty Hariata tried to teach my cousin, Kiwa and I but she gave up on us. We were both so nervous.

“I was in my thirties when the pōua and tāua at Tuahiwi asked me to karanga for a tangi. I nearly died. I was in the kitchen making a trifle and my heart started pounding and my knees were knocking. I got through that, but performing karanga never gets any easier.”

Aunty Kui believes Ngāi Tahu needs to support and encourage young women keen to learn but believes young mothers need time to grow into the role.

“Young mothers carry our future generations and the protection of unborn children was always paramount, so a spiritual korowai was placed around them and they were not permitted to do the karanga.

“Our times have changed but the role of kaikaranga is still one for a woman who understands that when you karanga for Ngāi Tahu, you represent the whole iwi and it is your obligation to ensure the hapū and iwi are being portrayed in the best possible way. It is a big responsibility. It is a duty and an obligation that we need to fulfil because we are the faces of our tūpuna.”

Maatakiwi Wakefield (Ngāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Te Atiawa, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Mutunga), is one of a younger generation of Ngāi Tahu women taking up the mantle of kaikaranga.

“I now see our kuia generally thinning out and our generation starting to fill the gaps a lot earlier than we would have done traditionally. There have been huge social influences on our traditional practices and while I’m a believer that anyone can karanga, I don’t think everyone is a kaikaranga. There’s a big difference between the two.

“A kaikaranga understands the role deeply and she understands the responsibilities that come with it – from manaaki manuhiri to the safety of manuhiri. It’s not about the glitz and glamour of being out the front as a lot of young women seem to think; there’s much more to it than standing out front and being seen.”

It is important to encourage and nurture young people in regards to karanga, says Maatakiwi. However, it is also vital that they be taught more than just words.

“Now I see this traditional stuff going into schools and kids are being taught words, not the artform, by people who are not of their hapū, or even of their culture. They’re missing out on the traditional tribal rituals of listening and learning. Karanga has become a curriculum subject and they’re mimicking sounds, not sitting alongside their nannies and learning what it all means. That does grate with me.”

Te Whe Phillips (Ngāi Tahu, Tainui, Maniapoto), 70, of Rāpaki, was working in the Rāpaki kitchen when she was first called upon to karanga 20 years ago. Although nervous and unsure, she made it through the occasion, but says she went home embarrassed and vowed never to find herself in that position again.

“When Te Arawa whānau arrived at Rāpaki earlier than we expected for a tangi that day, I had to make some quick phone calls to find out what to do. One of the kaumātua told me to write haere mai three times on my hand, call the guests on and make them welcome. That was my introduction to karanga. I was so nervous I was nearly sick,” she says.

She enrolled at Canterbury University to learn te reo and then spent five years studying at Waikato Polytech and Waikato University. When she returned to Christchurch to find one of the Rāpaki kuia had passed on, she was asked to step up to the role of kaikaranga.

“I felt proud because I knew then I could do it. Karanga is not just about calling out a few words; it’s about tapping into the wairua and I think the days of reading a karanga off a piece of paper, that faking-it-till-you-make attitude, are gone. I think you really need to know te reo and it’s up to the individual to make that commitment to language – or they shouldn’t be on the pae or doing karanga,” she says.

Hana O’Regan (Ngāi Tahu), 38, was just 16 when her father, Tā Tipene O’Regan asked her to karanga on behalf of his family at a function at an urban marae in Wellington.

“I wasn’t prepared spiritually or mentally. I knew the words but I felt sick. But I got through it and people complimented me. I only agreed to do it on the condition that the kuia in attendance knew I meant no disrespect,” she says.

Hana believes karanga should be a process of informing the other side about key messages. That might be delivering information about someone who has passed away; about what the special purpose of an event is; or key information about lineage.

“A knowledge of te reo does become important because if you’re not able to decipher information from the other side because you don’t speak the language, you may inadvertently show disrespect. If your goal is to afford the karanga the status and mana it traditionally had, then you should aspire to be able to perform to that level, with te reo.

“Karanga is a ritual of engagement that requires an ability to communicate message and emotion. It’s a dialogue, so if you can’t understand what the other person is saying, it’s a one-sided conversation. You might get it right by chance but without competent language skills there is a lot of room for error.”

Hana says there is a different reality today when te reo is not always the first language and people are not exposed to karanga on a regular basis in a natural way. The opportunities to learn are no longer the same, so it is inevitable that the quality of karanga will be compromised.

“I pay homage to those with limited proficiency who have done what they could in a phase of cultural impoverishment to maintain our protocols and to do what they could to respect our manuhiri and support key functions of the marae with limited capacity.

“I would never belittle those with limited te reo because without them our marae would be dead. I think those with limited te reo are still able to perform parts of the function and roles of the kaikaranga with what they know, but it’s important they keep safe within that and I would hope they’d aspire to be better by learning te reo. Our people have never been ones to accept mediocrity in the long-term,” she says.

Aroha Reriti-Crofts (Ngāi Tahu/Ngāi Tūāhuriri has two older sisters but has been doing the karanga for several years.

“I believe it’s the choice of the whānau and if a woman wants to do karanga, she should be given the opportunity to learn. Our tāua were always the ones to do the karanga here at Tuahiwi; I don’t ever remember younger women doing it. It wasn’t until I had had my own children that I was asked to do the karanga – when I was in my fifties or sixties.”

She teaches several young women herself, but doesn’t agree with schoolgirls doing karanga on the marae.

“Karanga is for women. I went to a marae years ago and a child was doing the karanga. I felt that was an insult to one of our kuia, who had to respond. That should never have been allowed to happen. Karanga is about experience. It requires someone with knowledge and insight. It’s not for kids.

“I love to do the karanga and I love hearing the karanga. It’s the most beautiful sound yet. It’s wonderful going back to Rātana and listening to the kuia there. They’re telling beautiful metaphoric stories with their karanga. And if I could be half as good at karanga as my tāua was, I’d be happy. She was fluent in te reo and you could hear her for miles.”

Read more about:

Befitting the occasion