For the love of the longfin eel

Apr 3, 2016

It’s probably the world’s largest eel, and it’s a renowned climber – able to scale tall waterfalls. But the large-scale dams on the Waitaki River hamstring our endemic longfin eels from accessing their habitats, thereby threatening their long-term survival. However, help is at hand, as kaituhi Mark Revington reports.

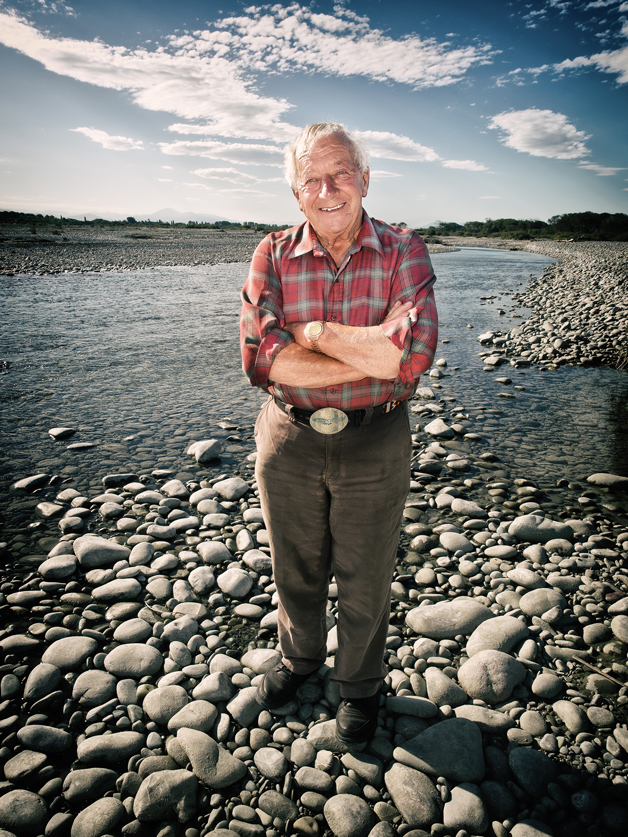

John Wilkie

When adult longfin eels are ready to leave New Zealand to release their eggs somewhere in the South Pacific, John Wilkie (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu – Kāti Hāteatea, Kāti Huirapa, Ngāti Hawea) is there in the Waitaki valley to give them a hand.

As juvenile eels, known as elvers, move upstream looking for somewhere to live, John is there to help them past dams on the Waitaki River, the large braided river that drains the Mackenzie Basin.

The eels’ journey is part of a cycle that is thousands of years old. John Wilkie has been part of it for the past 15 years, and for the past five years, Patrick Tipa (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu) has been helping him.

“I can remember as a kid we used to catch and eat tuna,” Patrick says. “We always wanted to catch the largest eel.” Now, he looks after their survival.

John and Patrick’s passion ensures life goes on for the longfin eel in one of the most modified landscapes in the country, a place where people have fished, hunted for birds, and gathered and cultivated plants for the past 1000 years.

The Waitaki river starts at the foot of Aoraki. It flows through three lakes – Benmore, Aviemore and Waitaki – and through three hydroelectric dams, one at the foot of each lake. Its tributaries include the Ahuriri and Hakataramea rivers.

Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua, Te Rūnanga o Moeraki, and Te Rūnanga o Waihao are the kaitiaki rūnanga for the Waitaki catchment.

“I have a huge affinity for them. New Zealand is the only country in the world where they live. They are bio-accumulative, so they can tell us so much about waterways. They are an amazing animal.”

John Wilkie Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu – Kāti Hāteatea, Kāti Huirapa, Ngāti Hawea

The longfin eel (Anguilla dieffenbachia) is the largest freshwater eel in the world and is unique to New Zealand. Its life cycle is complex, and many aspects are still unknown to science. Over his years working with the eels John Wilkie has developed a particular kinship for these animals, which he says become almost like pets, a sentiment shared by Patrick Tipa.

“I have a huge affinity for them,” says John. “New Zealand is the only country in the world where they live. They are bio-accumulative, so they can tell us so much about waterways. They are an amazing animal.”

The work on giving eels a hand up was started years ago by Ngāi Tahu customary fisheries expert, the late Kelly Davis. “It started with surveys and studies by Kelly in the Waitaki system,” says John. “The outcome was a trap and transfer system on the Waitaki. The elvers are trapped and then taken further upstream.”

Recently the work has been given a technological twist thanks to Iain Gover from Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu who has developed a field data collection app that records details of the catch to a central database.

Longfin eels undergo a dramatic transformation as they get ready for their journey into the Pacific. They grow slowly and can stay in freshwater for years. Studies show that males migrate on average after 20 years and females after 30 years.

They live in a variety of waterways, including farm drains and large ponds. As they ready for their long journey into the Pacific, their bodies change colour.

If they aren’t caught and helped downstream to spawn, they can remain locked in waterways inland. To catch them, John and Patrick rely on Iain’s technological wizardry, and their knowledge of eels.

“One of the first things I learnt was if you want to know about eels, you have to think like an eel,” says Patrick. “Where would you go? What environment would you look for?”

John says it amazes him sometimes that they are still catching mature eels in the back country, despite their work in shifting elvers upstream. “I still get really excited when I catch anything over four kilograms. I’ve been doing this for five years and I keep thinking there can’t be a lot more up here.”

The elvers arrive from the ocean as tiny glass eels, and slowly change colour to grey-brown as they move upstream. Although tenacious climbers, obstacles like the Waitaki dam can be too much to overcome. Therefore, John and Patrick trap the young eels and move them into the high country. Eels grow into maturity in the high country once they find somewhere suitable to live.

The Waitaki dam is the first obstacle along their path, says John, and all sorts of methods were tried to overcome the problem, including fish passes, which didn’t work.

A large part of their effort has been negotiating access to waterways in the high country, a process started during the land tenure review process, says John. “During that process we got to know the high country farmers, which made access much easier. The interest they have in the programme is amazing.”

When TE KARAKA caught up with the pair, they had just been up at Ōmārama Station, where Country Calendar had been filming. Part of that included coverage of the work of John, Patrick, and others in ensuring the longfin eel’s survival.

Patrick has also visited schools in the area to raise awareness of the issues, including several visits to Ōmārama School, where interest in the eels and waterways has led to other projects, like native planting to improve habitats.

And although Meridian Energy, which manages the Waitaki hydro scheme including eight power stations from Lake Tekapō to Lake Waitaki in the MacKenzie Basin, has often been painted as the bad guy, the company has put money and resources into trapping and transferring eels.

But it is still a huge job, and the information the men have gathered over time is crucial. “I often say to John that the knowledge he has is invaluable,” says Patrick.

“For me it’s a big learning curve. It has become a passion.”

Despite eels not being included as a taonga species in Schedule 97 of the Ngāi Tahu Claim Settlement Act 1998, there is recognition that when it comes to the Waitaki catchment, they are a taonga.

While the catchment has changed, perhaps irrevocably, due to hydroelectric generation, farming, and pollution, and the longfin eel population is generally thought to be in decline, the work of John and Patrick and others may tip the balance in the longfin eel’s favour.

“We are trying to get to the point where it is sustainable, and we still protect the interest of mana whenua,” says John. “When we catch and measure the mature eels, we only take those over four kilograms. And there is the knowledge that the eel you are looking at, and weighing and measuring, you will never see again.”

About the longfin eel

Longfin eels live mainly in rivers and inland lakes, but can be found in almost all types of waters, usually well inland from the coast.

Eels are slow growing – a longfin may grow only between 15–25 mm a year. They can also live for many years. Large longfins have been estimated to be at least 60 years-old.

Longfin eels breed only once, at the end of their life. When they are ready to breed, they leave New Zealand and swim 5000 kilometres up into the tropical Pacific to spawn, probably in deep ocean trenches somewhere near Tonga.

When they reach their destination, the females lay millions of eggs that are fertilised by the male. The larvae are called leptocephali, and look nothing like an eel – they are transparent, flat, and leaf-shaped. The larvae reach New Zealand by drifting on ocean currents.

Before entering fresh water, the leptocephali change into a more familiar eel shape, although they remain transparent for up to a week after leaving the sea. These tiny “glass” eels enter fresh water between July and November each year, often in very large numbers.

Eels take many years to grow, and it can be decades before an individual is ready to undertake the long migration back to the tropics to breed. The average age at which a longfin eel migrates is 23 years for a male, and 34 for a female. The adults never return, as they die after spawning.

Sources: Department of Conservation, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand