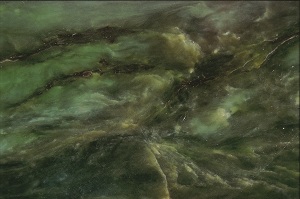

Pounamu mana

Apr 10, 2014

Nā Rob Tipa

“It gives the mana back to the stone — that’s what we’re aiming for,” says Ngāti Waewae rūnanga chairman and general manager of the newly-formed Waewae Pounamu, Francois Tumahai.

“It gives the mana back to the stone — that’s what we’re aiming for,” says Ngāti Waewae rūnanga chairman and general manager of the newly-formed Waewae Pounamu, Francois Tumahai.

He is talking about Poutini Ngāi Tahu and West Coast miners signing up to a ground-breaking agreement to return pounamu to Ngāi Tahu and deter the illegal black market trade in New Zealand greenstone.

The idea had been floating around for years, but the initiative came from Ngāti Waewae and Makaawhio, kaitiaki of the takiwā where most pounamu is found.

Ngāti Waewae’s takiwā stretches north of the Hokitika River to Kahurangi Point and inland to the Southern Alps. The land between the south bank of the Hokitika River and north bank of the Poerua River is jointly managed by both rūnanga, and Makaawhio’s takiwā extends from the Poerua River to Piopiotāhi.

Francois said the aim of the agreement was to provide the industry with a sustainable supply of quality pounamu at a reasonable price.

To achieve that, the rūnanga needed to find some way to encourage miners to return pounamu to Ngāi Tahu.

The black market trade developed after the Crown returned ownership of all pounamu to Ngāi Tahu under the terms of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998.

From that point, people were legally obliged to return all pounamu in their possession to the iwi, but Francois says there was only one example of that happening, from a Hokitika family, the Maitland whānau. No other pounamu had ever been returned.

At his initiative, Ngāi Tahu approached New Zealand Petroleum & Minerals, the agent representing the Crown, and they agreed to add the Finder’s Fee Agreement to all new mining permit holders within pounamu management areas.

“The key is New Zealand Petroleum & Minerals is on board with it,” he said. “They’ve been fantastic and have done everything they can for us. It’s quite an achievement to get that level of engagement.”

The agreement was sent out to all mining operations south of Greymouth, covering areas where most of the Coast’s pounamu is recovered, and has now been in place for two years.

It encourages miners to contact the rūnanga and work with Ngāi Tahu to return any stone found as a by-product of their operations.

About 19 companies have signed up, and five companies have brought in three and a half tonnes of pounamu in the last six to eight months.

Miners were not legally obliged to sign up to the agreement, Francois says.

“To date we’ve had good buy in from the mining industry. I suspect it’s going to take a few years to build a relationship with these guys, and with some we probably never will. However, we are hoping to achieve that.

“The majority will come on board and that just takes time to get around and meet and talk to them.

“A lot have signed up to the agreement, but haven’t found any pounamu yet. A lot don’t know what it looks like in its raw form and could be digging it up without recognising it.”

Building a working relationship with miners hinged on an appropriate model. At 5–10% of the value of pounamu, it wasn’t worth miners’ efforts to recover it. So the rūnanga raised their offer to 50%.

“To date we’ve paid out in excess of $40,000 to miners and the stone is starting to flow in,” Francois says.

“We’ll value a piece of pounamu with the miner, and pay them 50% of the agreed value. It’s purely a commercial arrangement so we get the pounamu back and we reward them for extracting it.”

The deal gives the miners a cash return for a by-product of their operations that they would be digging up anyway, so the agreement could contribute significantly to the economics of their operations.

Francois believes the agreement is starting to stem the flow of greenstone on to the black market. He thinks it will stop the illegal trade with other New Zealand manufacturers and prevent people selling stone overseas.

He says it was beneficial for Ngāi Tahu to build a stockpile of good quality stone to draw on for prestigious gifts for its commercial partners, and to provide a reliable supply for its own carvers.

“We don’t want to exhaust our resources, as China has. The whole goal of the operation is to get to the point of supplying the industry with quality pounamu at a reasonable price and to make it sustainable.”