Tā moko rising

Oct 18, 2012

“I think there has been a shift in attitudes over recent decades,” says Marcia Te Au-Thomson, 60, who received her moko kauae (on the chin) just last November. “I believe it comes back to education, and what is being taught in schools is an important part of that. Influential people have also stepped up and placed a value on things Māori, and that brings wider public acceptance of who we are.”

This is the first time Te Karaka has sought to present personal stories of Ngāi Tahu who have chosen to receive moko on their faces.

Wearing it on the face, says Ōtautahi master carver and tohunga moko Riki Manuel, shows a great commitment to the culture: it is an indelible part of how the world sees you as a person.

He remembers how, as the 1970s became the 80s, young carvers were increasingly interested in tā moko. “It was natural progression. We were already doing the shapes in wood, and wondering what it would be like to do it for real on skin.’

There was a carving of one of Riki’s ancestors, Iwirākau, in Dunedin’s museum. He enlisted his mates to help copy the patterns onto his own body – an event so unusual that it made television news.

Wider acceptance took a while. Some elders initially thought the art form too sacred and better left, he recalls. But the fledgling practitioners were ready to jump into the broken waka, figuring they could swim. They began to research the art form, rediscovering its history and traditions, bringing it back to life with modern tattooing equipment.

The increasing numbers of people offering their skin is a reversal of fortune for an art form that almost disappeared in the 20th century (even earlier among men).

If art is well, then people are well, says tohunga moko Derek Lardelli, who is regarded as one of Aotearoa’s finest tā moko artists. “It’s part of an identity revival that gives expression to being the indigenous people of Aotearoa.

“As we’ve moved into a globalised world, we’re looking for ways to be distinct, to claim a distinct place in the world – not just Māori, but all New Zealanders.

“Tā moko is the mark of this land, found nowhere else.”

Kaituhituhi Deborah Diaz captures the voices and stories of nine Ngāi Tahu whose faces bear the marks of their bloodlines.

Rua McCallum

Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Hāteatea

Photograph Raoul Butler

I had my moko kauae done on the anniversary of my mother’s death, almost to the day. It wasn’t about commemorating my parents’ deaths; more about celebrating my life.

I’d attended a wānanga at Arai-te-uru Marae where we broke into groups to kōrero about what moko meant to people, and luckily I was in this group that was mostly kaumātua. I had all these preconceptions about who was “good enough” or “eligible” to have moko kauae, but these kaumātua spoke about it differently – as a rite of passage, normally taken by young women at puberty, to show they were moving into a new phase of life.

It was probably there, on the spot, I decided to do it. My parents’ deaths and all of the changes I was making in my life were my rite of passage. This would signal my rebirth, my change, my transformation, my new life, my new beginning.

That year, 1996, had been probably the most pivotal year of my whole life. My son came to live with me after 10 years away. My mother was ill – cancer, heart attacks, on oxygen; my father also suffering failing health. As a family we resolved to live together and take care of each other. On 14 June, my father passed away. Mum went three weeks later. Within months I miscarried a baby.

I was ready to end my life – well, I was ready to not be here. It was just a bit much to cope with all at once. I came to the realisation that I wasn’t going to jump from a bridge, weighted with stones, and drown myself and my sorrows. Instead I made changes to my life. At the time, I thought I was “perfect”, that I was “right”. I needed to stop trying to change everyone around me, to fix them. I had to change me, honour me, and figure out what I was supposed to be doing, because if I wasn’t in balance, how could things around me be?

I took my design to Rangi Kipa who added some lines, his touch, based on my story. We talked about it a lot. It was after midnight that night when he did it. Barney Taiapa and his then partner, the late Ranui Parata, were at the wānanga – he had officiated at Dad’s tangi, and Ranui was my midwife who awhi’d me when I miscarried my baby. Their presence at this time completed the circle; helped close a chapter.

It was at this time that there were two deaths at home and one at Arowhenua. There was I, with my raw moko sitting raised on my chin, and all the Ngāi Tahu aunties were going to be at these tangi. I felt, “Oh my gosh, I am going to be judged, they are going to say something.”

I was in the hongi line. None of the aunties said anything. Until I got to Auntie Mahana Walsh. She looked at me with a really staunch, grim look on her face and I thought, “Here it comes …”

And she keeps staring at me, and staring at my chin, and she’s not saying a word, not one word. I’m starting to freak out when all of a sudden she just gestures to the top of my lips and says: “You need just one line, across the top of your lips, that’ll balance the whole thing, but I think it’s absolutely beautiful.”

All of me just went ahhhhhhhhhhh.

There are aspects of the design I keep to myself, but it encapsulates my three children, the one I lost being the fourth. One side is my mother’s, the other my father’s whakapapa.

The outer lines were added by Rangi and he referred to them as my roimata, the tears shed for my parents and my baby. There are also lines referencing the navigational paths of Arai-te-uru and Uruao, two of our waka.

While I was having it done, a kaumātua said to me that now I would never be alone – maybe not in the in the sense of having company; rather being connected to something bigger than me. Being connected, yes, that’s what he meant.

The night it was done, I remember being so buzzed out, on a tremendous high. People who know me say it lasted two years, and balanced out after five or six years. I think I might be normal again, now, whatever normal is. It’s been 16 years.

After her pivotal year, Rua went on to become a playwright, composer, researcher, advisor and scholar. Right now she’s working on the Ngāi Tahu exhibition space in conjunction with Te Pae Māhutonga and Toitū Otago Settlers Museum, which reopens in December after major refurbishments.

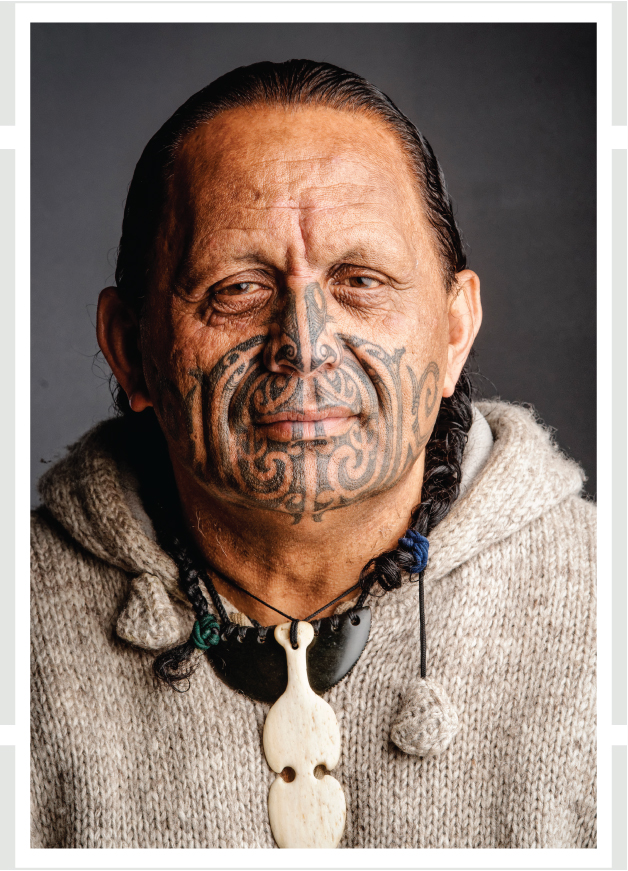

Te Mairiki Williams

Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Atihaunui-a-Pāpārangi,

Ngāti Hauiti ki Rata

Photograph Tony Bridge

Tā moko is a subtle, humble tribute to whakapapa Te Ao Māori in its purest and traditional form. It embraces the wellbeing of all. Such taonga acknowledges the recipient as a kaitiaki of ancestral lineage who will nurture traditional practices for future generations.

Tikanga is paramount to sustain this tradition. Our kāhui kaumātua, pōua and tāua advise those whom they see as ready to take on that kaitiaki role on behalf of whānau, hapū and iwi. To step up to the mark (so to speak) embraces their whakaae, their agreement. All the kāhui kaumātua rōpū need to give their blessing. If even one expresses doubt, accept it and wait for the right time – arohamai, ā tōna wā, ka puāwai.

Much of the understanding of this taonga came from nestling under the korowai of a tōku rangatira, tohunga Hēmi Te Peeti. To be invited to work alongside him at wānanga tā moko nationally has been a very humbling experience. You learn to eat, breathe and sleep the kaupapa 24/7.

To awhi the tohunga involves reciting karakia tawhito and ensuring the wellbeing of recipients: stretching the skin and body to accentuate the beauty of tā moko, ensuring hygiene is paramount and embracing the taonga in its most pure, practical and traditional form. Traditional karakia occurs prior, during and at the end of the wānanga.

If the tohunga calls you to help him, make sure you’re on the next flight. Why? The karanga from the tohunga or your old people only comes once. Anei te karanga (this was the call to me). One day Hēmi said, “Hold your head up, hold it up straight”, and he drew half of it on. “Give me five minutes and I’ll have the table set up; you’re on next.”

Five minutes may not seem like much, but working alongside the tohunga prepares you. Others know when you’re ready. Ka rere āwhiowhio te wairua (be empowered by a strong spiritual presence). When that spirit arrives, saying “kāo” is not an option.

The left side of my face embodies the pūkaea, war trumpet, and acknowledges journeys in the principles of traditional weaponry. The right-hand side embodies the essence of wellbeing, whakapapa, and being asked by my elders to be a kaitiaki of ngā korero o neherā. Such ancient knowledge was recorded in the wall paintings in caves, and that korero has been continually nurtured in whakairo and tā moko.

When receiving the taonga in 2003, it was humbling to be told by one kuia that no other Ngāi Tahu man carried traditional tā moko on the face.

In receiving taonga tā moko, the protocols are paramount. Traditional practices are foremost – being free of smoke, drugs, alcohol and violence. These traditions accompany moko on any part of the body. Tā Moko is the lineage from Te Ao Mārama (the world of light), to Te Ao Kōhatu (the holistic world) to Te Ao Wairua (the spiritual world).

If you’re going to be gifted the taonga, then keep yourself safe and be a good role model. It’s not something you should get done just because it looks good. This is a special journey to prolong and sustain life for your whānau, hapū and iwi.

Whakapapa not only keeps Te Iwi Māori safe, it embodies an inclusiveness – where decisions are made with humility and with others in mind. It’s about celebrating being Māori in a traditional and holistic form. Tikanga and traditional practices enrich, enhance and empower Māori to live life to the fullest.

Maybe we should all get tā moko.

For my whānau, keeping the taonga safe in particular means being careful about photographs. It’s not a tourist attraction or to be exploited for commercial purposes. One person asked to take a photo, and the reply was: “If you take a photo, then I’ll have to eat you.” Consequently, no one has asked since. The beauty of tā moko is humility.

The most frequently asked question is: ‘Does it hurt?’ If that be the whakaaro, he tohu tērā, ā tōna wā, ka hoki mai (you’re not ready). The second question is: Is it finished? Ko te whakautu, ko te Tohunga tērā (the answer lies with the tohunga). He could ring at any time and say, “Let’s finish it off.”

As the tohunga Hēmi Te Peeti said, tā moko is the epitome of wellbeing in Te Ao Māori. He aha te mea nui? He whakaiti, he whakaiti, he whakaiti. Tātou i a tātou. (What is the sustaining power of mankind? Let humility prevail).

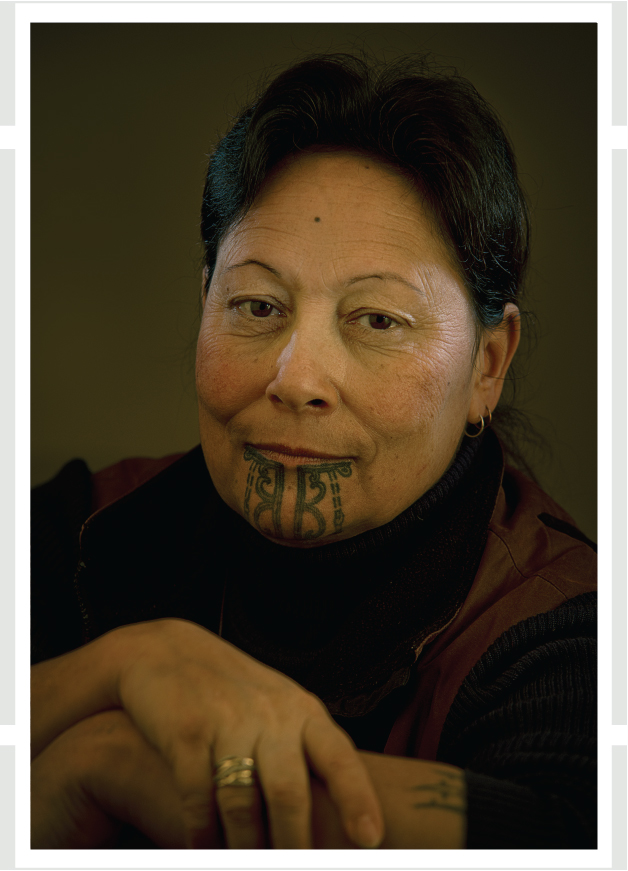

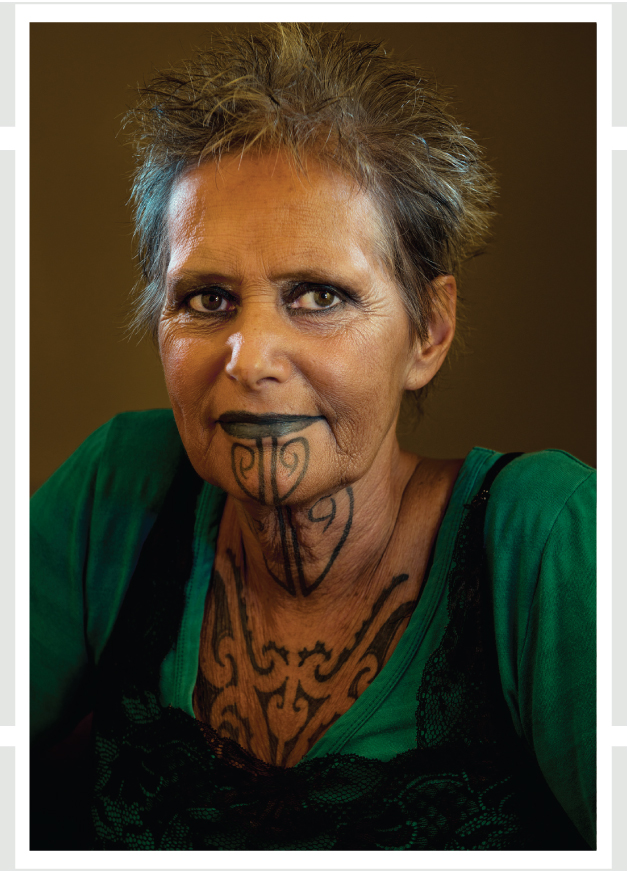

Hana Morgan

Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Te Arawa, Ngāi te Rangi, Ngāti āwa

Photograph Raoul Butler

While I was born here in Bluff, I was raised amongst my mother’s people in Whakarewarewa. I grew up in a village within a hapū, Tūhourangi Ngāti Wāhiao. One of my fondest memories as a child was sitting in the baths with all the kuia who had moko. I was just fascinated, fascinated with lines. I used to stare at them. I just loved moko. Back then a lot of the kuia had moko, and growing up in the pā you used to run around and into everybody’s house, and they fed you, cuddled you, looked after you.

The moko was very common, but only among the kuia.

By Mum’s generation, nobody was being done. That would have been post-war, I suppose. When we had only one kuia left in the pā, I asked my Mum, “Why don’t you get one?”

She said, “Too sore.”

She’d seen it done in the old way as a child; it was a whole lot of blood, and they never flinched or made a sound. My mother was absolutely not having any of that. And by that point I think people thought it was gone, a part of the old world.

But I loved looking at the moko and at the kuia.

I came back to Bluff as a young woman and helped develop the marae; we were quite young to be doing that. There was nothing visibly Māori here, or little to none, back in 1973. There was what they called the Māori house and the Waitaha Hall for functions. After the wharekai was opened, I’d chat with my peers and we’d say we should all get a moko when we turned 40. But no-one was game enough, and it wasn’t the thing to do. It had almost become invisible.

As they started to revive the moko in the past 15, perhaps 20 years, I would see the women and see photographs and think how beautiful it was. A few years ago Mark Kopua, who had come down to do a tā moko wānanga, asked me about my kauae. “Funny you’d say that,” I told him, “because I’ve always wanted one, but now that I have the opportunity I’m a bit scared.”

Three years later I said yes. I’d given myself enough time to get the courage.

I’m thrilled with the revitalisation of the arts. I love seeing the other women and it’s almost like we have a link; an unspoken thing. I don’t know if it’s our moko talking to each other or if it’s the wairua that goes with it.

I think I was fortunate that my parents who raised me understood the beauty behind it; the beauty of the moko. If I think back, there were photos on the wall of two of my kuia with moko kauae – my grandmother’s sisters – from the time I was a baby. And I had a picture of my great-grandmother, and she had one as well.

Mihipeka Wairama of Tūhourangi, painted in 1912 by Charles Goldie, is Hana’s great-grandmother.

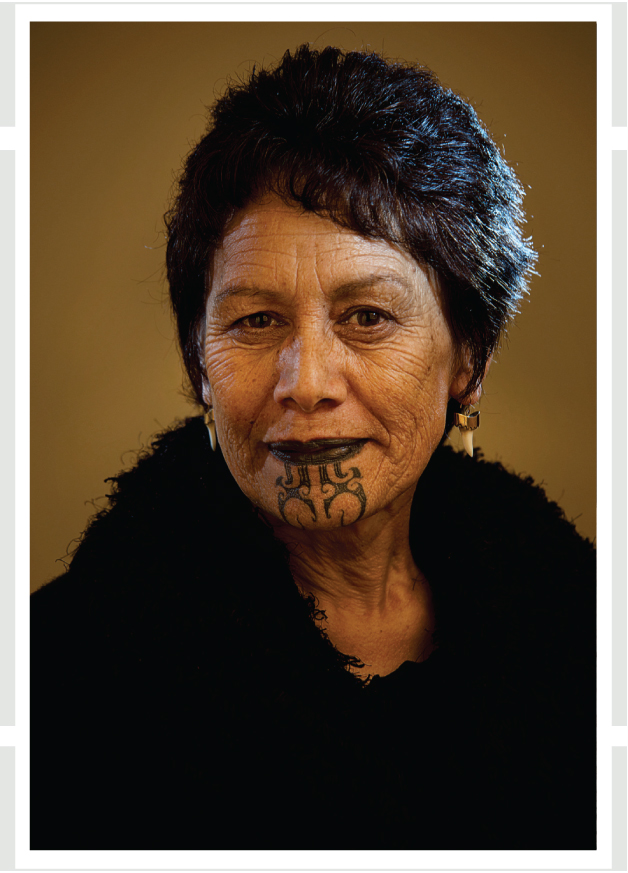

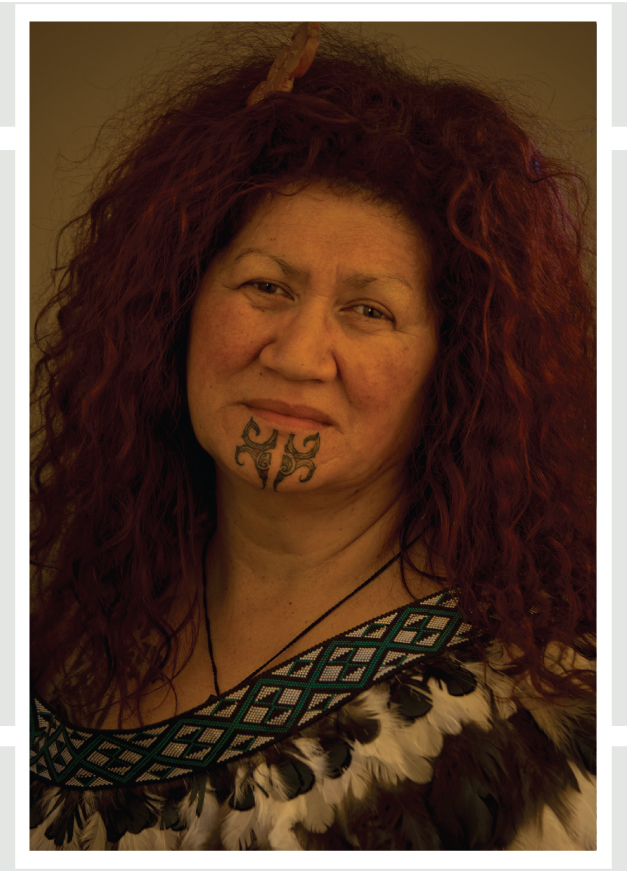

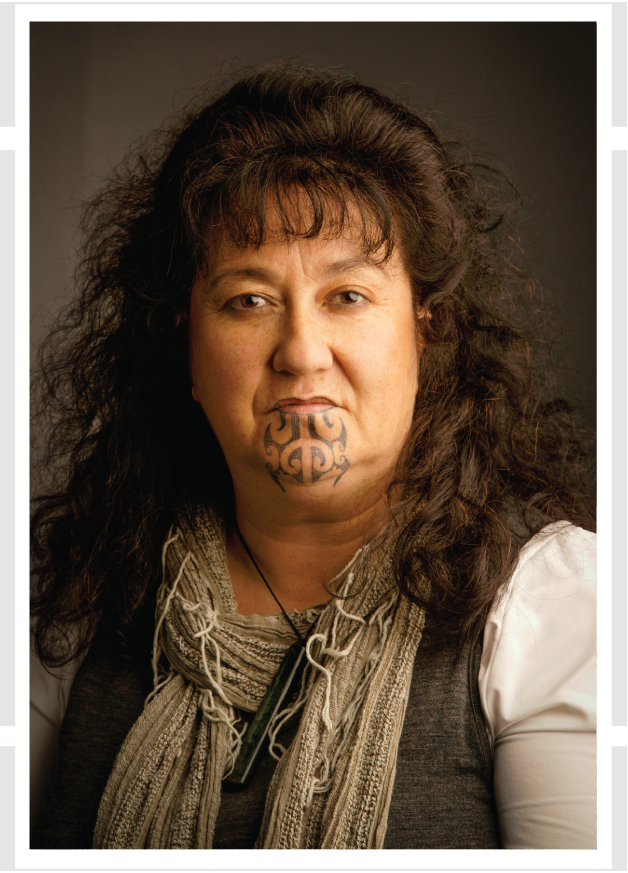

Marcia Te Au–Thomson

Ngāi Tahu

Photograph Raoul Butler

I was coming up to 60 last year and thinking I’d like to do something to mark that milestone. I’d spent the previous 18 months reflecting heavily on my life, and the appropriateness of a moko kauae seemed quite relevant to my journey thus far. All of the women I’ve known with moko kauae have been on wonderful journeys, no two ways about it. It’s almost as if we didn’t have a choice about getting one; it was meant to happen. Some people say it’s as if the moko has always been there, and one day it reveals itself.

In order for that to happen for me, I needed to get serious and do the rounds of kōrero with whānau, especially my children. Auē! To my amazing kids and moko: “Big Shuga Luffs” from Tāua.

In preparation for the occasion, I spent a special whanau-ngatanga time with whānau and friends. Two of the ladies had come up with pictures of what they thought my moko kauae might look like. Both of their designs were pretty much in sync with the tohunga (thanks Tracey and Shaye).

The night before was spent with my two stunning sisters, Winsome and Ora. Winsome took us to the urupā and spoke to our Mum and Dad. Arohanui ōku tuākana kōrua.

The occasion of getting the moko kauae was massive! I was very fortunate and indeed privileged to have my whānau and extended whānau with me on the day, along with our rangatira, Michael Skerrett.

The design is by te tohonga o tā moko Herewini Tamehana who comes down to Invercargill twice a year. He’d already done one on my forearm, and I really like the man – you have to have faith and trust for something so precious.

On Facebook one night he asked, “Whaea, what’s your iwi affiliation?”

I told him, “My daddy was born in Bluff, my mum was born in Moeraki, and I was born a twin”. That’s all I wrote. When he arrived down with the design, I was humbled by what he had captured.

It is about whānau and aroha ki te tangata. The design represents the mana of Motu-Pōhue and Moeraki, and incorporates the green of our pounamu and the red of our blood lines. I’m Ngāi Tahu to the bone.

It feels like it has always been there and many people don’t notice anything different about me. At the same time, it reaches out and makes a connection with people. Some of the reactions have been amazing.

Not long after having it done I went to a kaumātua luncheon; and a tāua ran her hands down my kauae and said, “Ah! So that’s what it looks like.” They were hugging me; my kauae was all loved up. There was joy and excitement, and the comments they made were so lovely.

Complete strangers will come up to me to hongi. Restaurant staff have come out of the kitchen. It’s happened outside The Warehouse in Nelson – I was waiting for my husband to park the car and a woman with two wee kiddies came straight over, and said “Kia ora, whaea” and had a hongi with me. Even the men will hongi with me to acknowledge the moko kauae.

I think there has been a shift in attitudes over recent decades, which prepared the way for the return of moko kauae, I believe it comes back to education, and what is being taught in schools is an important part of that. Influential people have also stepped up and placed a value on things Māori, and that brings wider public acceptance of who we are.

Nō reira ka nui te mihi ki a koutou taku whānau whānui.

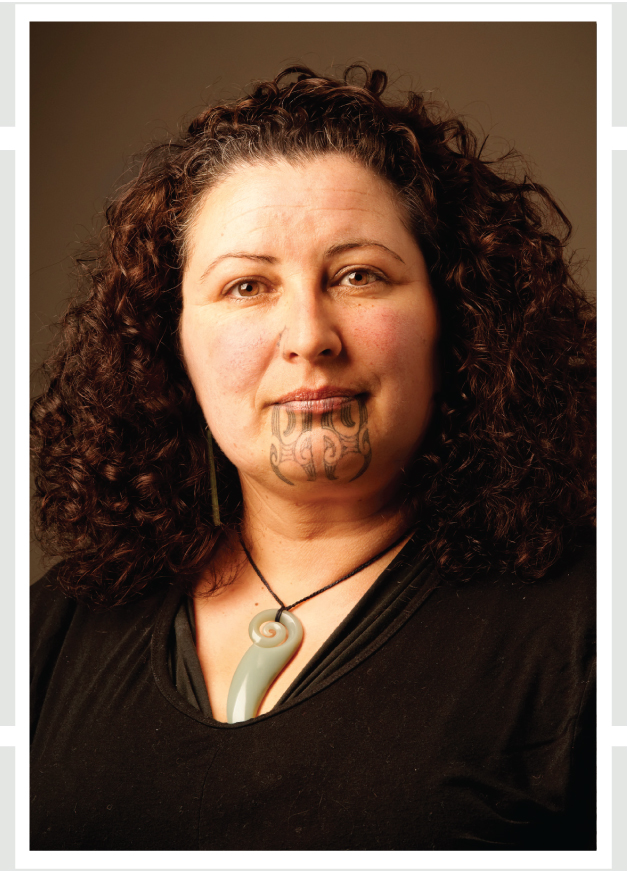

Leisa Aumua

Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Hāteatea, Kāti Huirapa, Ngāti Hāmoa

Photograph Tony Bridge

Prior to having moko done on my legs six years ago, I talked it through with my uncle, the late Kelly Te Maire Davis. I wanted to make sure it was appropriate within the family context. His response was, “Why wouldn’t it be? Everything you do – as a parent, as a teacher, as a being – is Māori. Why should you not have a symbolic tohu to acknowledge that?”

He actually said it was a little weird that I didn’t already, as I’d studied Māori art and Māori art history. I’d never even considered a moko kauae, but he said, “At some stage of your life you might. If something happens to me or I’m not around, you have my blessing.” I think that planted the seed.

For me, tā moko is a way of acknowledging pride in my whakapapa and choosing to live and breathe as Māori. It affirms my chosen path. When I had my kauae done three years ago, I realised I was at a stage of my life where I had overcome various challenges and I was comfortable with who I am. I don’t aim for perfection but I’m confident in my moral direction. I did feel that I should be fluent in te reo, but I’ve come to realise that learning is a constant process over a lifetime. The importance of keeping the continuum going is very significant.

Leading up to it, our family spent a number of years in the North Island living and breathing a fully cultural environment. We were in regular contact with tohunga of whakairo, moko and raranga. We were involved in the restoration of the National Army Marae (Rongomaraeroa o Ngā Hau e Whā) in Waiouru. Opportunities developed for my husband, Steve Carrick, and I at various marae, to sit on the pae and to karanga. We’d always seen ourselves as mahinga kai people, working in the kitchen; so it was a time of extension and growth for us, with the community drawing us out of our comfort zone.

I was meeting and having wānanga with a lot of fellow artists, and our family have a rapport with tohunga moko Te Rangi Kaihoro and his family. Eventually I decided to have my kauae done. I discussed it in depth with my husband, and was fortunate to know tohunga moko Derek Lardelli, Ngāti Kaipoho and Hēmi Te Peeti to talk with. It became clear that for us, the journey and the process was more important than the outcome.

Each half of my moko is a manaia (guardian) figure in profile, facing opposite ways. They come together to form a third looking straight out from my face in a frontal position– together they see the past, future and the present; they are the guardians of all paths. The eyes have been stylised as waves in reference to Tangaroa, where water is the essence of life.

I get a lot of comments about my nose – people want to know why I’m lopsided – but as an artist I like asymmetry! The puna ihu on my nostril is a creation symbol (which I love because I’m a māmā); it refers to the breathing of life into the first woman Hine-Ahu-One. Some people might have filled in the circle, but for me that would signal that something has reached fruition. Even if I live every day to the full, I don’t think I’ll reach fruition until I have actually passed – and I’m not there yet.

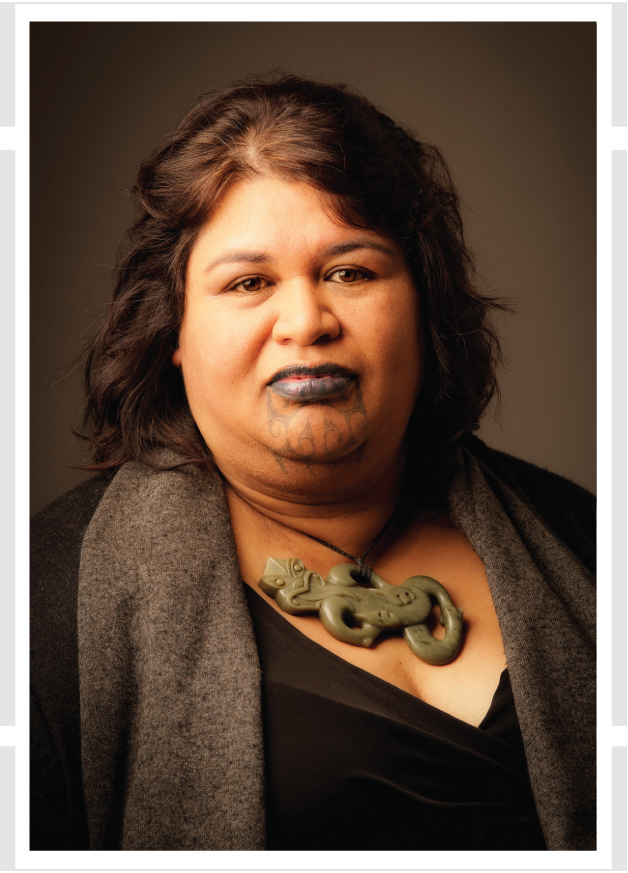

Khyla Russell

Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Rapuwai

Photograph Raoul Butler

If you know my story, I was a late entry into tertiary education and had a PhD in six years (Educating Khyla, Te Karaka, Kahuru 2008). When you put on a set of doctoral gowns, everyone knows you have a qualification – for us, the moko was something from the family that would sit alongside that.

If you’re looking for something deep or spiritual, it wasn’t like that. My sister just said, ‘It’s time you got your tā moko’, and we did. My sisters Eleanor and Raewyn and I have always worked like that: if something needs to be done, we discuss it and go from there. The moko was not one of our big discussions.

The design on my face by Hine Forsyth (Kāi Tahu) is practical – from throat to mouth. The moko was always going to reflect what you are gifted with. I talk, sing and teach. This is an expression of those things – for others to have and share on my skin (because I don’t see it unless I’m looking in the mirror).

Tā moko artist Christine Harvey later added my children on my chest. Later still we added my sisters on my back. It’s a way of having your family with you, even if a lot of them aren’t.

It was 2001 when I got my doctorate and moko. I wouldn’t put my tā on a continuum of cultural revival – it was just the right time. You can’t return to a culture if you have not left it. We lived on the kaik and lived the life. There were women with moko in the wider family, and going back further the tradition would have been for women to have moko on half of the face. There were also men with love heart tattoos and the like. It was all just part of the wallpaper of life.

Every moko will be different, and reflect where a person has come from. The East Coasters were kaimoana people. We understood the tides, when and where to fish. We were interested in things like the stars. It was about keeping ourselves safe and, if not, bringing the bodies home.

Dad (Boydie Russell) had the saying, “Fix yourself.” It was about making sure we had a conversation in our head about the things that would keep us safe. That was our tikaka.

Gems of wisdom were often passed on when we went out fishing with Dad. One of us kids would pick it up – at least one of us would be listening – and it formed a kind of collective knowledge. The family holds the whakapapa in the same way; we all know different knowledge layers.

Khyla was appointed full professor at Otago Polytechnic in January, recognising her international reputation in indigenous research and leadership. Kāti Huirapa Rūnaka hosted her professorial address at Puketeraki Marae last month. The hākari was the stuff of legends.

The Ōtautahi trio below share ancestry through neighbouring marae on Horomaka (Banks Peninsula) and each of their moko kauae signifies a kaitiaki role to carry and preserve aspects of family knowledge.

Puamiria was asked to receive her moko kauae by tohunga Derek Lardelli as part of his Master of Fine Arts degree. That scholarly endeavour involved tracing bloodlines through iwi migrations down the east coast of the North and South Islands and recording that whakapapa in tā moko.

At the request of whānau, Derek later returned and Maatakiwi and Mairehe Louise received their moko kauae.

Puamiria Parata-Goodall

Ngāi Tahu, Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Kahungunu

Photograph Tony Bridge

My first reaction? Anywhere but my face! It wasn’t something I’d expected to consider until I was older, much older. A lot of doubts ran through my head – was I worthy, could I handle the expectations, was it the right time, what would my family think.

I had four weeks to work through all that; I cried a lot! I grieved for the person I was leaving behind. It is a process that makes you think about who you are and what’s important.

My moko kauae has always been there. It took the expertise of my tungāne Derek to bring her to the surface. Within the design is a hoe (paddle). This hoe has been passed down from generation to generation within my whānau. For the moment, I look after the hoe, in time I too will pass it to the next generation.

I am humbled by my kauae. She often reminds me to change the lens on my world view, to trust my instincts. In daily work, most decisions are made in the head. When you operate in te ao Māori, often you are guided by your intuition, your heart and your ability to see and listen to the tohu around you.

Maatakiwi Wakefield

Ngāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Te Atiawa, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Mutunga

Photograph Tony Bridge

I always knew I was going to wear a pūkauae. My nanny sat me down when I was young and told me I would have one. Back in those days it wasn’t well known. It was something only seen in photos and books, so I didn’t really give it much thought at that age.

When the request came, it was obviously the time for it to happen. It was a natural progression for the path I’m walking. It wasn’t the first tā moko that I’ve taken, but it is the most visible. She’s probably the first thing that greets you when you see me. She has her own mauri, sometimes she does her own thing, but it is good when our energies work together.

Visibility does bring expectations and with them some pressure to be a role model. But I have learned how she is perceived is how she is portrayed. The most empowering experience I have ever had was to be in a room full of Māori women who all had a pūkauae. The sense of unity and unspoken bond was amazing.

Mairehe Louise Tankersley

Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Kāti Irakehu, Kāi Tūtehuarewa, Kāti Huikai, Kāi Tūāhuriri

Photograph Tony Bridge

I was shocked – it was an honour to be asked, but I also knew the huge responsibility that went along with receiving moko kauae. I was told that if it was meant to be, then I would know, but it wasn’t until the early hours of the morning it was to be done that I felt at peace. I’d gone to Rapanui (Shag Rock) to do my karakia in preparation for the day, and as the sun rose I felt my wairua settle into me, and I knew it was right ; that I was ready.

The return to our traditions, I think, is a sign of well-being for our people. It’s about going back to our natural state of being. Tā moko was something beautiful and something to be respected. It was our whakapapa and connection to our ancestors.

There is a saying: Kia whakatōmuri te haere ki mua (we walk backwards into our future) –

it’s about looking back to the knowledge and traditions of our ancestors to guide us as we move into the future.