New day rising

Dec 21, 2016

The Kāti Huirapa marae at Arowhenua has been a focal point for Kāi Tahu for more than 100 years, and has entered a brand new dawn with its redevelopment.

Kaituhi Takerei Norton and Mark Revington report.

Above: Arowhenua Upoko, Tewera King at the dawn blessing.

“Ko wai te ingoa o te whare nei?”

“Ko Te Hapa o Niu Tireni.”

It has always been known as Te Hapa o Niu Tireni. The name means “The Broken Promises of New Zealand”, and refers to the Crown not fulfilling their promises made to Ngāi Tahu when purchasing the majority of Te Waipounamu from the iwi during the 19th century.

For more than 100 years, the marae at Arowhenua has been a focal point for Ngāi Tahu, especially in the tribe’s struggle to get redress from the Crown. The original marae on the present site was opened in 1905. Two years later, Te Hapa o Niu Tireni hosted its first major tribal hui. Tribal representatives gathered from around the takiwā to discuss the recently-passed South Island Landless Natives Act. This hui became pivotal in regenerating tribal efforts to continue to advance the Ngāi Tahu Claim, with a new fighting-fund and committee established.

In the 1980s and 90s, the marae continued to be a central point for the iwi, hosting important tribal hui as settlement with the Crown became more likely. Its history and geographic location, more or less in the middle of the Ngāi Tahu takiwā, made it an ideal gathering place.

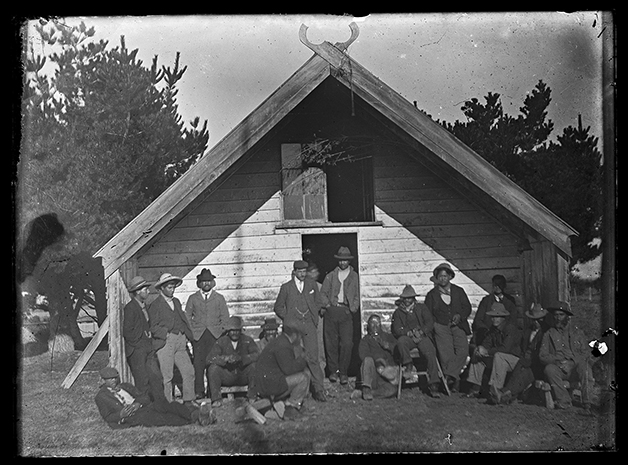

Above: Photograph of the original Te Hapa o Niu Tireni Marae at Arowhenua (Reference: South Canterbury Museum, 5389).

The renewed marae was opened in early November this year, starting with a dawn ceremony on a cold, wet morning, followed later by a pōwhiri. It marked the end of 10 months of construction and around 15 years of kōrero and planning for the $3.3 million redevelopment.

The original, distinctive entrance of the whare, its face, has been retained. Behind it is the redevelopment, which is centred on the historic wharenui and includes a modern kitchen and a kaumātua lounge. The legendary cookhouse is to be relocated.

It has always been known as Te Hapa o Niu Tireni. The name means “The Broken Promises of New Zealand”, and refers to the Crown not fulfilling their promises made to Ngāi Tahu when purchasing the majority of Te Waipounamu from the iwi during the 19th century. For more than 100 years, the marae at Arowhenua has been a focal point for Ngāi Tahu, especially in the tribe’s struggle to get redress from the Crown.

Te Hapa o Niu Tireni is the principal marae of Kāti Huirapa, standing between the junction of two rivers: Te Umu Kaha (Temuka) and Ōpihi. The original pā, Te Waiateruatī, was situated near the mouth of the Ōpihi River and was home to Te Rehe, the influential Kāti Huirapa rangatira. Traditionally Arowhenua was the site of a large forest and cultivations. After Arowhenua Māori Reserve 881 was allocated in 1848 as part of the Canterbury Purchase, people began moving to Arowhenua from Te Waiateruatī.

The first whare was opened in 1875. Located directly across the road from the present marae, it was also named Te Hapa o Niu Tireni. It was destroyed by fire in 1903, and a meeting was soon held to consider the next steps following this catastrophe. It was agreed to build a new hall.

A building committee was soon elected, and work began on raising the necessary 400 pounds.

In 1904, Premier Richard Seddon visited the Arowhenua Native School during his South Canterbury tour. Local Māori apologised for not being able to host the Premier at the existing hall, due to the recent fire. Premier Seddon promised to provide 200 pounds towards building a new hall if the hapū raised the other 200 pounds. The money was raised and a new hall was built.

Above: Hon. Colonel Pitt addressing the crowd during the opening of Te Hapa o Niu Tireni Marae in 1905 (Reference: Canterbury Museum, 1923.53.365).

The official opening was a glamorous affair. The grounds surrounding the hall were covered in marquees. Manuhiri were welcomed with a pōwhiri, and flags were raised as part of the official proceedings. Following the banquet, Colonel Pitt, who represented Premier Seddon, took questions from the floor. Not surprisingly, they all focused on the Ngāi Tahu land grievances.

Over the next 100 years Te Hapa o Niu Tireni continued to be the central hub for Arowhenua. Originally the marae did not have a dining room. On a nice sunny day, trestle tables were placed outside between the hall and the cookhouse, or dining occurred inside the hall itself, even

for tangi.

Shortly before he passed away in 2015, Te Ao Hurae Waaka, affectionately known as Uncle Joe and influential in the development of the new marae, vividly recalled those early days. “If you had a tangi, you had to use the stage where you put the tūpāpaku, but you had to use the hall itself for a meal, cos we had no backroom.”

Cooking was done by the men over large open fires in the cookhouse using heavy cooking pots collected from around the pā. “I inherited the job of going around the pā picking up the big pots on a horse and cart. They all had their own names and marks on them, you know, these great big cast iron pots. I used to take them down to the marae where they did the cooking with them in the open fire,” Uncle Joe had recalled.

“They had a thruppence and a box thing for the power, but it only gave you light. We never had anything to cook with, you know, unless we went out to the big cookhouse and lit up the big fire. We had no money then. We used to run euchre if we wanted to buy anything to use – we would save every bloody penny we could and buy something.”

Te Ao Hurae Waaka (Uncle Joe)

“And when the hui or tangi or whatever was finished, they had it all spotlessly clean again, and I’d load the horse and cart up and deliver them back home to the other houses. They all had a little mark on them to say where they’d come from. If you mixed them up, look out.”

Mattresses were also collected from around the pā on the tractor. In the back room behind the hall was a small kitchen. In those days there was no water system, so water was carted up from the river.

“We went down on a horse and cart and filled up milk cans with water from the river. Take it up to the hall and they’d tip it into the water tank. That was a job for young people like me,” said Uncle Joe. “And the other thing was carting wood from the riverbed to light the fire to cook with. We used to cut that up and take it up to the marae, and used it in the open fires out in the cookhouse.”

There was no heating in the whare. Hay was laid down on the floor to keep everyone warm overnight. “Uncle Burt Leonard had this great big tractor where they’d bring in the hay,” recalls Mateka Pirini, née Anglem. “They’d scatter all this hay along on the floor, and they’d put the forms down and then they put the mattresses on top of that where you slept. They would also pick up bowls, blankets, different bits of kai, and whatever else that people had.”

“They had a thruppence and a box thing for the power, but it only gave you light. We never had anything to cook with, you know, unless we went out to the big cookhouse and lit up the big fire. We had no money then. We used to run euchre if we wanted to buy anything to use – we would save every bloody penny we could and buy something,” said Uncle Joe.

For tamariki growing up in the pā, it was a great life. Days were spent swimming down by the old Temuka Bridge, bobbing for eels, playing in the hedge at the marae, and gathering blackberries and watercress around the pā . In front of the marae there was a great big pond that would freeze over in winter – a great spot for ice skating.

The marae was like a sports venue. Table tennis, netball, basketball, and tug-of-war were all played inside the hall or out on the grass in front. “Yeah, it was really cool because we used to have Weka Hopkinson. Him and his family used to come over and set up table tennis,” says Mateka. “I think they’d set up about three lots of table tennis tables, and then they’d have that going, then they’d also have netball going or basketball, but we’d just be running up and down screaming, throwing the ball around and everything like that.

“They had a ladies great tug-of-war team here, and Benny Benson and Pōua Reuben used to let us kids all play – they had little tug of war teams for us young kids to learn, we played table tennis, they were marvellous, absolutely,” recalls Rita Heke.

By the 1980s the marae was in need of a major renovation. A team made up of Joe Waaka, Kevin Russell-Reihana, Mana John Wilson, Donnie Rewiti and Mokie Reihana set about sanding, scraping, and painting the hall inside and out.

The new redevelopment takes into account the future needs of Kāti Huirapa while acknowledging the increasing demands on space by whānau, hapū, iwi, and the community. It also recognises the unique history of Te Hapa o Niu Tireni in relation to Te Kerēme, and the culture and history of Kāti Huirapa as the hapū looks towards the future. The new renovation will nurture current and future generations while retaining the face of the old whare, and its distinctive name will help preserve many years of history.

Then under the leadership of Aunty Kera Browne and Michael O’Connor the dining room, new kitchen, and ablution block were added to the back of the marae. This work team included Glen (Timo) Timothy, Loraine Reihana, Margaret Home, and Brian Goodman. Later on Uncle Michael supervised two new workers, Colleen Fowler and Ernest Johnston, to add the patio between the cookhouse and hall.

While all that was happening, George Russell had a team of young men, under the guidance of a retired landscape designer simply known as Pop, who created the large veggie garden in the paddock next door, as well as the gardens surrounding the marae. Pipi Waaka ran the weaving classes over in the old school hall, teaching our wāhine tāniko and tukutuku panels.

Funding came from a mixture of MACCESS work scheme resources, funding from the government on a dollar-for-dollar system, and local fundraising. “We didn’t have any money – well the Ngāi Tahu thing didn’t exist, and we used to run card tournaments. People would donate prizes, make a few bob, and pay the power bill,” Uncle Joe said.

The new redevelopment takes into account the future needs of Kāti Huirapa while acknowledging the increasing demands on space by whānau, hapū, iwi, and the community. It also recognises the unique history of Te Hapa o Niu Tireni in relation to Te Kerēme, and the culture and history of Kāti Huirapa as the hapū looks towards the future. The new renovation will nurture current and future generations while retaining the face of the old whare, and its distinctive name will help preserve many years of history.