A vibrant presence

Jul 18, 2014

Renowned artist Cliff Whiting had a huge influence on Ngāi Tahu, says Tā Tipene O’Regan, who tells the story of how Cliff came to work for the tribe.

One of my earlier incarnations was as a lecturer in Māori Studies and New Zealand History at the then Wellington Teachers College, to which I was appointed in 1968. Not long before that my wife Sandra and I had been “mature students” in the college, and during a studentship of abundant revelation and new experiences, we’d been hugely engaged by a remarkable breed of teachers and innovative thinkers.

One of those was the creative art educator Gordon Tovey, who had already had a profound influence on the development of a whole new generation of Māori artists and art educators. What Tovey, and those he’d influenced, had released into New Zealand culture was a whole new pulse of dynamic innovation in the way Māori culture and tradition could be manifested through the arts.

They’d challenged the very concept of tradition itself, and, in so doing, had moved Māori artistic expression beyond the protective cocoon of museum-enshrouded, static, and repetitive forms into a bold new artistic language. However novel though, it was utterly and unmistakeably Māori in its form and in what it represented. One of the frequently-quoted figures at the heart of this process was Cliff Whiting of Te Whānau ā Apanui – commonly in tandem with another artist from Te Kaha coast, Para Matchitt.

I was not then (and neither am I now) an artistically informed or enlightened person. What appealed to me was the dynamism of the process, the vigour, and the life that it was breathing into the very sense of what “Māori Art” was. I could see it flowing on out into contemporary Māoridom. I recognised it all as a manifestation of something I was myself becoming deeply interested in within my own corner of Māori Studies. This was the notion that the dominating and distinguishing characteristic of Māori culture was its old heritage, of what I had begun to call in my writing, “Dynamic Adaptation”. I was looking through the glorious turbulence surrounding me to a cultural characteristic that goes back to the foundations of Polynesian and Māori culture.

It was our own process. We owned it. Pākehā culture was not shaping and controlling Māori culture. Our Māoritanga was going to be what we wanted it to be – shaped and coloured by us. We were not going to be victims of cultural division – we were the new ethnic multiplication sum!

Tā Tipene O’Regan

I was seeing this notion everywhere I looked – in Polynesian archaeology, prehistory, and ethnology; in te reo, and, most evidently of all, in the way our own tūpuna had managed their 18th and 19th century experiences of cultural contact in Aotearoa. What the Pākehā scholars were calling Māori “folk art”, the museum fish hooks the ethnologists were describing as “European-style Māori”. Sir Āpirana Ngata’s adaptations of lyrics from The Desert Song and other musicals, the Māori newspapers of the 19th century – all of these things were not manifestations of cultural decline or “Europeanisation” unless, of course, that was the way one wanted to view them!

What I began to realise was this whole creative phenomenon exploding around me was an absolute assertion of my emerging Dynamic Adaptation thesis. These were all expressions of Māori culture reshaping and evolving itself. It was our own process. We owned it. Pākehā culture was not shaping and controlling Māori culture. Our Māoritanga was going to be what we wanted it to be – shaped and coloured by us. We were not going to be victims of cultural division – we were the new ethnic multiplication sum!

Of course, these emergent ideas were not taking place in a vacuum. These were the early days of what was already being called “the Māori Renaissance”. The Māori post-war demographic tide had already turned – although it would still be a while before the Power Culture recognised it. The great urban migration was well under way. The Māori world was alive with growth and change, and beginning to flex its political muscle in the world of New Zealand life and politics. We were all getting excited about race relations theory and the 1961 Hunn Report, rugby relationships with South Africa, Māori education policy, and so on. Visiting American scholars were writing books about us (with a somewhat pungent level of accuracy) and enraging our politicians; and the “Februarys of our discontent” were beginning to wind up at Waitangi. The disgrace of Bastion Point in 1977-78 and the wrenching social and political experience of the 1981 Springbok Tour were still to come. It was a vibrant, disputatious, creative national culture being powerfully impacted by external events from oil shocks to Vietnam. It was all on!

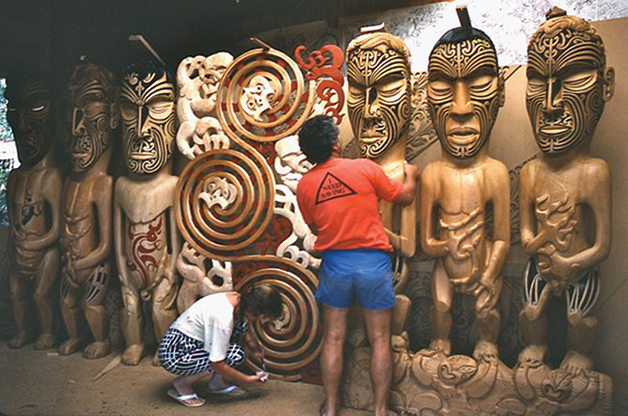

Cliff and his wife Heather working on the Law Courts mural.

Back in my early lecturing days we developed the practice of taking our largely middle-class students out on field trips to rural marae to expose them to some degree of Māori life and culture, a world from which they were almost completely insulated. The marae communities of that period were almost devoid of younger people as a result of urbanisation, so we would work with our students on various community projects and the kaumātua would come into the wharenui and engage with the students in the evenings.

It was in about 1970, in the course of one such exercise at Koriniti on the Whanganui River, that I first became associated with Cliff Whiting, of whom I’d heard so much – largely from mutual friends. He had just started teaching at the Palmerston North Teachers College. We had our students working under his direction on the redecoration of the wharenui, Te Waiherehere, on the Koriniti Marae. He was exploring the idea, which was to become a trademark of his practice, of actively involving the community in marae restoration and thus reinvigorating the local culture through the arts. The kaumātua of that marae, Te Rangi Pokiha of Te Ati Haunui-a-Pāpārangi, was to become a treasured family friend and a profoundly supportive pou whakakaha for both Cliff and myself.

Although our friendship ripened from that point, it was only in 1976 when Api Mahuika of Ngāti Porou enticed me on to the Māori Advisory Committee of the New Zealand Historic Places Trust that Cliff and I began to grow an active working relationship. He was leading the trust’s programme of restoration of marae around the country, and we were all heavily engaged in the wider protection of Māori heritage – the archaeological as well as the built heritage. It was archaeological site protection that brought Atholl Anderson of Ngāi Tahu onto that advisory committee, shortly followed by Te Aue Davis of Ngāti Maniapoto – both of whom were to later play a major part in the subsequent Ngāi Tahu Claim and cultural development. We were to work together in that context for the next 14 years, and the relationships we forged were both powerful and productive. Te Aue was already a noted weaver, and was now emerging as a distinguished student of traditional history. That was later to evolve into her work with the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography and for the New Zealand Geographic Board, of which I was a member. Cliff used his creative skills to work with us both on the 1990 Māori Map Project and the publication of the Māori Oral Maps Atlas, and other projects of that kind.

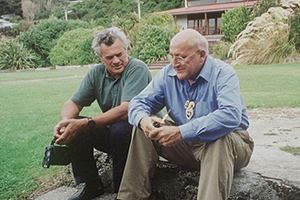

Cliff and Tā Tipene on the day Tā Tipene was made Ūpoko Rūnaka o Awarua.

In the late 1970s, Bill Solomon, Te Rakiihia Tau, and myself were attempting to turn the attention of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board back towards the cultural revitalisation of Ngāi Tahu. I had been strongly influenced by my association with the resurgent Māori renaissance and was beginning to articulate the idea that if our generation was to successfully “relight” Te Kerēme o Ngāi Tahu, we needed to rebuild our own cultural strength to go with it. We initiated policies to support our marae and begin a process of revitalisation of te reo. Our efforts were – compared to the Ngāi Tahu effort of today – very modest. There was virtually no money and, after all, in terms of cultural competence, we weren’t that hot ourselves! We did, though, have the unwavering support of our kaumātua – both those on our trust board and those beyond it in our rūnanga. Most of them, although confident in their identity as Ngāi Tahu, were culturally deficient themselves, and they knew it. That was, however, no deterrent to their tautoko!

My first major effort was to persuade Cliff to come south with me to a hui at Tuahiwi in 1982. From this hui was born the trust board tukutuku project – six panels for the Ngāi Tahu Trust Board boardrooms. At the conclusion of that hui, tasks were being assigned to prepare materials and equipment, and Cliff asked who was going to find and prepare the kiekie for the tukutuku. Rakiihia Tau leapt up and volunteered, “Ngāi Tūāhuriri will get the kiekie, two truckloads – what’s it look like?” And, in due course, he delivered! Those panels involved a whole lot of kōrero about the traditions being depicted, and a reworking of tribal memory by the people involved – all of whom were learning the skills from scratch. They took the panels away to work on in their respective communities from Kaikōura to Awarua, and the interest percolated through the tribe. The panels were completed and erected in 1983.

My own creativity was limited. I was just the “go-to man” – organising materials, preparing the frames for building the panels, applying the primer, securing the tools, boiling the water for the kiekie, and so on. That pattern was to be repeated later with both the Takahanga and Awarua projects – particularly with Takahanga.

Once the long battle for the recovery of the Takahanga land was finished following the death of kaumātua Rangi Solomon, Bill Solomon and his sister, Wharetutu Stirling, approached me to discuss the development of the marae itself. We first had to get an archaeological clearance from the Historic Places Trust – a major project in itself. With that done, I asked Cliff to come and run a wānanga based on his work on marae restoration in the North Island. I knew he had an amazing slide show record of the projects I referred to earlier. I said to him, “Just come and talk about marae – what they look like, how they work – all that!’’ That was the beginning of a whole series of preparatory wānanga, largely at Ōaro, learning kōwhaiwhai and tukutuku, with lots of work on te reo and waiata thrown in.

Cliff and I took a minibus full of Kaikōura people, together with a couple of packed cars, on a heke through the lower North Island and up the Whanganui River inspecting marae – everything from wharepaku to kitchen design arrangements. We were discussing the practicalities of marae layout and design, but essentially trying to expand the people’s confidence in making decisions about what they were building. It worked.

Cliff brought the great Ngāti Porou kuia, Ngoi Pēwhairangi, to teach te reo using her rākau method, and that started off a whole new dimension in our lives. We drew in our soulmate from the Historic Places committee, Te Aue Davis, and she brought her weaving skills to the task. As well, she began working with Bill and me on Kāti Kuri manuscripts and traditional history also. All this was being melded into the design and decoration of the marae. Cliff, Bill Solomon, and Te Aue formed a great affection for each other. The community adopted Cliff and his late wife, Heather, as their own, and he was completely hooked, intellectually and emotionally, on the project.

Most of the other papatipu rūnanga of Ngāi Tahu became involved, especially Awarua. Ngāi Tahu’s human capital in Māori artistic and cultural competency became expanded and enlarged. When Takahanga wharenui Maru Kaitātea was opened in 1992, it was a revolutionary advance in marae design, and greatly and widely admired.

Following the Takahanga project, Cliff secured a commission from the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin. He took the project to Kāti Kurī at Kaikōura, and led the project of building a large tomokanga (gateway portal) there. This was a further extension of his practice of community involvement – he never stopped being an educator. By the time it was finished, Wharetutu Stirling, Bill Solomon’s sister, had died. In 1994, a team of us travelled to Berlin for the installation and whakatūwhera. Te Aue Davis came with us as our kaikaraka. It was a very stimulating but emotional experience. I will never forget the memory of watching our little ope wandering through the great art galleries and museums of Berlin, looking in wonder at the treasures hanging there. We named the tomokanga, gateway, in Wharetutu’s memory, Te Kūwaha o Te Wharetutu. It stands there today – a dominating feature of one of the world’s great art museums; a symbol of the Ngāi Tahu renaissance.

From 1984 to 1994 I was a trustee of the then National Museum of New Zealand, and had become quite involved in the debates and the planning for what was to become Te Papa Tongarewa. In 1993, Cliff was appointed as kaihautū of the new museum, and he and Heather moved to Wellington. There was much talk about the evolution of a “truly national bicultural institution” – that was the notion that had been sold to us at the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board when the then Minister of Internal Affairs, Hon Peter Tapsell of Te Arawa, came seeking our support.

In his new job, Cliff got stuck with giving substance to the kaupapa in Māori terms. I worked with him on developing an articulation of biculturalism. The difficulty was that there was practically no agreement about what “bicultural” meant in that context. I recall turning up with Cliff to present our policy documents to Te Papa’s board, chaired at that time by Sir Wallace (Bill) Rowling. We said, “Well, here’s our view of the Māori dimension of biculturalism; who’s going to write up the Pākehā view?”. Of course, they hadn’t thought of that! There was a terrible argument. Bill Rowling became enraged. He said that it was not his job to define or describe Pākehā culture. Cliff was sensibly silent. I, somewhat rashly, took up the cudgels. “Well, you’ve been the bloody Prime Minister of the country, and now you’re leading the biggest single exercise in national identity we’ve ever attempted. If you can’t say who and what you are, who the hell can?’’ The poor man went off his head and the meeting was adjourned.

Te Ao o ngā Atua at CPIT.

The “Pākehā Establishment” still can’t articulate with any confidence or clarity what New Zealand Pākehā culture is – what it comprises, its variety and diversity, and all the commonalities within it.

To be fair, they’re pretty good at articulating what Pākehātanga is not – at defining it in the negative. The problem is that this is not much of a basis for articulating either the Te Papa vision or any half-decent national identity. It remains a challenge. Anyhow, at Te Papa, they stopped discussing the question, and Cliff turned to designing and building the extraordinary marae for Te Papa, Te Hono ki Hawaiki, which was opened in 1997. I turned my efforts back to the Ngāi Tahu Claim.

In 1999 I was invited to become Ūpoko Rūnaka for Awarua and found myself once again associated with Cliff and Heather. Cliff was in the process of extracting himself from Te Papa and before long, he and Heather moved to Bluff and set out on the huge task of decorating and adorning both our existing wharekai and the striking new wharerau, Tahu Pōtiki. It was Takahanga all over again – only more so. By this time Cliff’s professional practice had been hugely extended both in concepts and materials, and the Awarua project was to benefit hugely from that. The wharekai at Te Rau Aroha Marae is a riot of exuberant colour and innovative design that owes much to the great experiment that is Te Hono ki Hawaiki in Te Papa.

The most powerful effect of Cliff’s practice amongst us, though, is not so much the art itself, for all its imposing and vibrant presence. It is much more the way he pushes our kōrero and our whakapapa back to the forefront of our being. There is simply so much discussion and debate about the traditions themselves, their meaning, and their significance. That kōrero is translated into the art and invests it with meaning – with life. Cliff has the knack, as well, of picking up on the day-to-day mahika kai values in our lives, and pumping new meaning and significance into them – fish and birds, tītī and pōhā, appear in tukutuku panels alongside the poutama symbols and other traditional forms of spiritual significance. The treasures that our Awarua haukāika know about and are known for are seen right up there with all the “heavy Māori stuff” – our world and who we are is strengthened and affirmed.

Long before the great marae projects, Cliff completed his first commissioned work, the maihi for the Ōtākou Māori School, in 1964. It was a project he undertook with Para Matchitt. Later, in 1988 during his major mural phase, there was Te Ao o Ngā Atua at the Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology (CPIT), featuring Rākaihautū. Then, in 1990, three great works: the tomokanga at the Otago Museum, Ngā Kete Wānanga; the six powerful pou standing in the foyer of the Christchurch Law Courts building; and the two great carved pou standing in the Albatross Centre at Pukekura, Ōtākou.

In 1991, the Aoraki mural was completed and installed in the Visitor Centre at Aoraki, Mt Cook. This mural tells the oldest of our creation stories and was based on the karakia recorded from Matiaha Tiramorehu – the founder of Te Kerēme o Ngāi Tahu, the Ngāi Tahu Claim. The early morning dedication karakia was performed by our Arowhenua Rūnanga and I hold a vivid, life-long memory of the whakeke led by Sir Paul Reeves being called in through the gently falling snow to the karaka of Aunty Kera and Irihapeti Murchie. Standing sheltered in the grey early morning light, we were moved by the magic of the event and filled with admiration of our bare-chested and bare-legged toa, who were poised in the snow for their wero to the Governor General and his ope.

Ngāi Tahu is extraordinarily privileged to have such a huge proportion of Cliff’s prodigious output standing within our takiwā. We are even more privileged to have had his input into a number of major Ngāi Tahu development projects, each of which has fired and rekindled our cultural life as a people.

My role in our relationship with Cliff Whiting has been limited to that of facilitator, organiser and occasional producer of whakapapa and pūrākau. My job has been to recover land, find money, and argue with politicians local and national; as well as driving trucks and laying priming paint, drilling holes, and sanding. In our relationship beyond Ngāi Tahu, I negotiated the acquisition of his great signature mural, Te Wehenga, for the National Library, and dealt with the officials installing Tawhirimatea in the Wellington Meteorological Office. My task has been – from time to time – to service his vision.

Our relationship has not always been easy. At times it has manifested some extremely “dynamic adaptation”, but we have been linked together in a common cause – the refreshing of our culture and the expansion of our identity as Māori in the fabric of our society.

He hoa tūturu o te takata nei, ekari he hoa tūturu o te whakaari o Kāi Tahu!

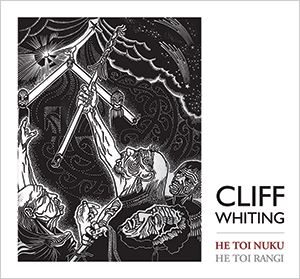

Cliff Whiting: He Toi Nuku, He Toi Rangi

This essay was sparked by a stunning book on Cliff Whiting and his work, published in November last year by He Kupenga Hao i te Reo, a Māori language education and research organisation based in Palmerston North.

This essay was sparked by a stunning book on Cliff Whiting and his work, published in November last year by He Kupenga Hao i te Reo, a Māori language education and research organisation based in Palmerston North.

Cliff Whiting: He Toi Nuku, He Toi Rangi, written by Ian Christensen, has both English and Māori texts and carries insights into the work of an artist who has made a remarkable contribution to Māori art over a career spanning more than 50 years.

Born in 1936, in a whare raupō beside the Kereu River, inland from Te Kaha on the East Coast of the North Island, Cliff has developed a recognisable style of contemporary Māori art, based firmly on his Te Whānau-a-Apanui tribal traditions, which can be seen in his marae building, and the public and individual art works he has completed. He has contributed his expertise and time to a large number of marae renovation projects, and was also the first Kaihautū of Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand. He has received many awards in recognition of his contributions, including

New Zealand’s highest honour, the Order of New Zealand (1998), and Te Tohu Tiketike a Te Waka Toi (2003).