Kā ara tūpuna Waitarakao to Wairewa: the ninety mile beach

Jul 17, 2014

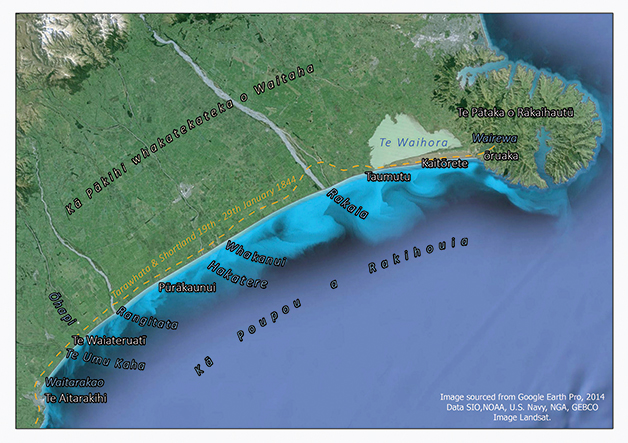

At sunset on 9 January 1844, Bishop George Augustus Selwyn stood atop the south eastern hills of Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū (Banks Peninsula) and gazed down upon the magnificent view of the vast plains to the south. He noted the apparently interminable line of the “ninety miles beach” which extended in a continuous line of uniform shingle, unbroken by headland or bay, all the way to the distant hills of Tīmaru in the south. As Selwyn and other nineteenth century Pākehā travellers learned, this ‘interminable line’ was part of a key travel route for Ngāi Tahu, a Māori ‘State Highway One’ that extended between lakes Wairewa in the north and Waitarakao in the south.

At sunset on 9 January 1844, Bishop George Augustus Selwyn stood atop the south eastern hills of Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū (Banks Peninsula) and gazed down upon the magnificent view of the vast plains to the south. He noted the apparently interminable line of the “ninety miles beach” which extended in a continuous line of uniform shingle, unbroken by headland or bay, all the way to the distant hills of Tīmaru in the south. As Selwyn and other nineteenth century Pākehā travellers learned, this ‘interminable line’ was part of a key travel route for Ngāi Tahu, a Māori ‘State Highway One’ that extended between lakes Wairewa in the north and Waitarakao in the south.

Named the ninety mile beach by Pākehā whalers, the route ran adjacent to the Canterbury sea-board, or Kā Poupou a Rakihouia (The Eel Weirs of Rakihouia). This traditional name refers to the posts or poupou put in by the Waitaha explorer Rakihouia when constructing eel weirs at the mouths of various rivers during his voyage along the eastern coastline of Te Waipounamu in the waka Uruao.

The apparent straight line of the beach was actually a great arc, uniformly shaped by the even, ceaseless pounding of the sea. Bookended at either extremity by the bluffs of Ōruaka and Te Aitarakihi, it typically took three to five days to travel its entire length and required numerous river crossings, and periodic deviations inland to avoid the hazards of cliffs, swamps and fissures in the coastline. Kāinga nohoanga (temporary campsites) punctuated the route at regular intervals.

Ngāi Tahu knowledge regarding this ara tūpuna is recorded in associated place names and tribal traditions. In his recollections of the Ngāi Tahu flight south following the fall of Kaiapoi Pā in 1832, Natanahira Waruwarutu described the typical pattern of walking, eating, river crossing and camping along this coastal travel route. Several highly descriptive nineteenth century accounts of Pākehā’ travelling the ‘ninety mile beach’ accompanied by Ngāi Tahu guides also exist. These include the journal entries of Bishop Selwyn (first Bishop of New Zealand) and Edward Shortland (Protector for the Aborigines) in 1844, Walter Mantell (Commissioner for Extinguishing Native Claims) in 1848 and Charles Torlesse (Surveyor, Canterbury Association) in 1849.

In the summer of 1843-44, Edward Shortland (Protector for the Aborigines) travelled the length of the east coast of Te Wai Pounamu undertaking a census of the southern Māori population. Accompanied by two Māori guides from the North Island, Shortland’s party was also joined by several different Ngāi Tahu guides on various legs of the journey. Among these guides were Poua and Tarawhata, the sons of the Kāti Huirapa rangatira (chief), Te Rehe.

Pōua escorted Shortland from Waikouaiti northward to the commencement of the ninety mile beach at Te Aitarakihi. From there, Te Rehe himself took over as guide, leading the party on to lake Waitarakao where his wife prepared them a meal of fish and potatoes before they proceeded inland to Te Waiateruatī Pā on the Ōrakipaoa River for the night. In exchange for payment of a blanket, Tarawhata then assumed guiding duties for the remainder of the journey north.

Setting out from Te Waiateruatī Pā, Tarawhata and Shortland travelled past the Ōhapi River where they feasted on tuna (eels) before camping at the Rangitata. The following evening an island in the middle of the seasonally dry bed of the Hakatere (Ashburton River) served as their campsite. On reaching the Whakanui, they filled water bottles left purposely on the banks for travellers as there was no fresh water between there and the Rakaia, a day’s travel away. This ‘desert’ leg of the journey was best undertaken very early or late in the day to avoid the risk of dehydration.

As they travelled, Tarawhata shared his extensive knowledge of the geography of the area with Shortland who was surprised to find that there were Māori names given to many small streams and ravines which he perceived were scarcely worthy of notice. Tarawhata also described and named the interior sources of the Rangitata and Rakaia Rivers. On arrival at the Rakaia, Shortland noted the local method of river crossing:

“The natives use a pole to aid them in crossing these rapid rivers. Two or three persons hold this pole, which they call a “tūwhana”, firmly about breast high, the strongest being stationed at the end pointing up the stem. Then they take advantage of the set of the current to get them from one shoal or shingle bank to another, always allowing it to carry them with it, while they strive to advance across it.”

From the Rakaia to the kāinga of Taumutu, Shortland and his party sustained themselves solely on kāuru, a nutritious sweet food produced from the cooked stems and roots of the tī kōuka (cabbage tree). The final stretch of the journey took the party along Kaitōrete, the large shingle bank separating Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere) from Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean). The hard relatively barren surface of Kaitōrete made for easy travelling. Ahead rose the peaks of Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū with Wairewa (Lake Forsyth) at its base and thence, the cliffy terminus of the ninety mile beach.

When early Pākehā explorers, surveyors and government agents arrived in Te Wai Pounamu, in the mid-nineteenth century, they struggled to negotiate the landscape alone, both in physical and cultural terms. Pākehā readily became lost, particularly when negotiating the vast swamplands that were a feature of the Canterbury landscape. River crossing was also particularly fraught and the myriad waterways in the area posed a very real threat of drowning. As a consequence, Pākehā travellers usually engaged Māori guides to assist them as not only navigators and porters but also as interpreters and cultural advisors. For Ngāi Tahu, these arrangements allowed a measure of control over where Pākehā travelled within their rohe (tribal area) and also availed them of the opportunity to be privy to Pākehā activities. Guides were often paid in either money or goods, but their assistance was sometimes provided voluntarily.

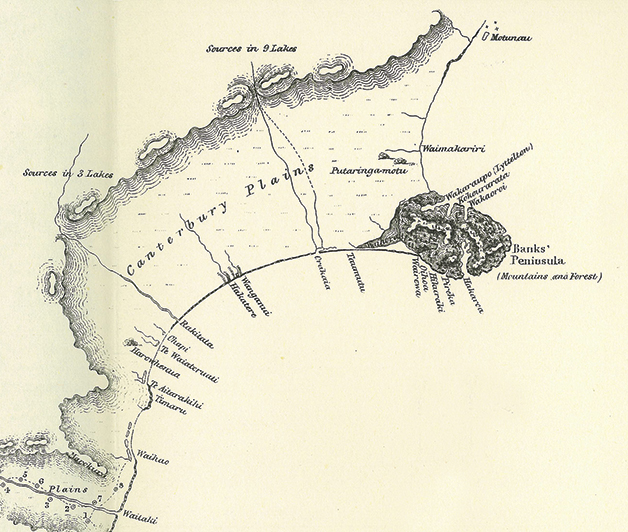

This detail is taken from a map of the South Island which appeared as a frontispiece to Edward Shortland’s book Southern Districts of New Zealand (1851). The map includes detail provided by Tarawhata during his and Shortland’s journey north along the ninety mile beach in 1844.