Ka taki mai te māuru When the nor’wester howls

Jul 1, 2018

Over the centuries, Māori have developed extensive knowledge about local weather and climate. These learnings form the basis of traditional and modern practices of agriculture, fishing, medicine, education, and kaitiakitanga.

New research conducted by Te Kūwaha-o-Taihoro-Nukurangi, the environmental unit at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), has found this knowledge to be alive and well among Ngāi Tahu whānui. However, its future is at risk from rapid climate change and the passing of knowledge holders. Apanui Skipper reports.

At the inaugural Māori Climate Forum in Wellington in 2003, formal recognition of traditional Māori understandings of weather and climate variability and change was made, with several Māori elders highlighting the importance of giving a greater account of this knowledge of the environment.

Since then, several projects have explored the subject further, but many questions remain. A key question is how new opportunities might be created to promote learning about subtle signals in nature that can reveal much about changes in weather and climate

conditions.

Building on these initial efforts, in January 2016 Te Kūwaha-o-Taihoro-Nukurangi was awarded research funding from the Vision Mātauranga government science programme, as part of the Deep South National Science Challenge. This funding enables the team to work closely with knowledge holders from Ngāi Tahu whānui to identify, revitalise, and promote the use of environmental indicators to forecast weather and climate extremes.

The research programme is one of six Deep South Challenge Vision Mātauranga projects. I was privileged to lead this work, and together with the project team I travelled extensively across Te Waipounamu to interview Ngāi Tahu kaumātua, fishers, and cultural practitioners. The journey took us from Te Taurapa o te Waka in the deep south at Awarua, to Waihōpai, Hokonui, Karitāne, Waimate, Te Umu Kaha, Wairewa, Rāpaki, Ōtautahi, Kaikōura, across to Arahura, and finally to Hunts Beach near Makaawhio on Te Tai Poutini.

Our research team gained unique insights into the diversity of the environmental indicators that continue to be used by Ngāi Tahu whānui to highlight, monitor, and plan for activities that are sensitive to changes in weather and climate. We were amazed at the diversity of fauna (including native birds), flora, atmospheric, and astronomical phenomena that are still identified and acknowledged as weather, climate, or seasonal tohu (indicators).

In one such tohu, snowfall on mountain ranges means that rivers will eventually rise, flooding the plains below – so whitebaiters have to be extremely mindful. To this day they keep a lookout for the river turning a dirty colour, a dead giveaway that the river is about to rise very quickly. Skilled and experienced elders were responsible for training the younger generation to survive in the wild by knowing how to recognise potential hazards such as this. Mistakes could be fatal, so reading the sky to predict the weather was regarded as a serious business.

Seasonal tohu, underpinned by an astute knowledge of local features of the maramataka (lunar calendar), allowed harvesters to plan appropriately for whatever type of season was predicted. When we spoke to Paul Wilson and his sisters Helen and Jan from Kāti Makaawhio, we learned that leaves dropping from the endemic, deciduous kōtukutuku (New Zealand tree fuschia) signalled the transition from kahuru (autumn) to makariri (winter).

Above: Krishna Smith, Apanui Skipper, and Cyril Gilroy at Murihiku Marae – Te Rakitauneke.

Throughout this kaupapa we discovered that tākata mahika kai (wild food harvesters) were able to provide the greatest detail. They had an intimate knowledge of seasonal harvesting practices such as muttonbirding, eeling, whitebaiting, and fishing. More importantly, they spent a lot of time outside, paying attention to what was happening in the coastal, estuarine, freshwater, forest, and alpine environments; and, of course, the atmosphere. If they failed to take heed of what the environment was saying, “He aituā kai te haere” (an accident will happen).

The influence of lunar phases on daily weather conditions and on the behaviour of taoka kai (traditional Ngāi Tahu food) habitat was regarded as particularly strong. The maramataka had both daily and monthly forms, and were developed depending on where the harvesters resided and where their chief resources were located within their wakawaka (traditional division of a harvesting area).

The nor’westers and sou’westers were recognised as bringing the most extreme conditions, although in Awarua, rūnanga chair Hana Morgan recollected that easterlies were known as bone-chilling winds that could cause breathing difficulties for asthma sufferers.

Te Māuru (the nor’west arch) narrative was spoken about at length. Those who still understood this distinctive weather phenomenon of Te Waipounamu explained that when Te Māuru was seen above Kā Tiritiri-o-te-moana (the Southern Alps), the height of the arch determined the intensity of a southerly expected the next day, usually associated with snowfall. The blustery nor’wester that causes havoc with airline pilots as they make their approach to land has also been found to be responsible for causing depression, irritability, and a lack of energy in some people.

Although climate change was not a key component of the research, our discussions revealed a unanimous belief that changes in local climate conditions are so significant that some traditional forecasting indicators are no longer reliable – a hypothesis for possible future research. A common observation from whānui who have spent their lives observing the environment was that climate change is “definitely here and now”.

This assertion was backed up with many examples. Long summers and mild winters are more frequent. Rivers are drying up, causing a great deal of stress on taoka kai, and in many cases, loss of taoka kai. Mahika kai areas are disappearing. Estelle Leask, passionate conservationist and chair of the Bluff Hill/Motupōhue Environment Trust, provided compelling evidence that the Murihiku region has been experiencing higher-than-normal temperatures. This has caused profuse flowering of Southern rātā (Metrosideros umbellata) on Motupōhue (Bluff Hill), in turn causing bird populations to explode, as well as pests. Tītī are having to fly further to feed – abandoning their chicks for longer periods. Other consequences of warming conditions were noted by Tā Tipene O’Regan when he observed that “kingfish, a fish species unknown to early Ngāi Tahu, are now being caught in greater numbers along the east coast of Te Waipounamu”. To top it all off, kiwifruit are growing in Invercargill – something unheard of 30 years ago.

Auē taukuri e! Ohorere ana te mauri kua hika te hoa. He wai kei aku kamo rite ana ki te tairere, nei kē taku uma mokemoke ana. Whakaroko whakakakau e hotuhotu nei. Moe ake rā e te tuahine, i te moeka o te tini,

i te maru o te ihi, o te wehi, o te mana. Te murau o te tini, te wenerau o te mano, haurokuroku te kupu kōrero, wētakotako taku hinekaro, porotaitaka tōku mahara auē, ka taki taukuri e.

It was with great sadness that we heard of the passing of Mandy Home, pictured above with Darren King and Apanui Skipper. Without her mana and extensive whakapapa connections, her many insights and good standing with her own people, this kaupapa rakahau would not have been successful. We are truly grateful for the time afforded with one another. During the course of this work Mr Butch Macdonald from Kaikōura – Kāti Kurī, also passed away. We acknowledge his deep connection to the natural world and contributions to this work. Me kī pēnei au ki a kōrua, e kore rawa te puna o te aroha e mimiti noa, moe mai takoto.

Tiny Metzger (Ngāi Tahu – Awarua) shared further evidence of environmental impacts in our southern regions, stating that recent storm surges had stripped the sand from the shores, exposing ancient campsites. This unprecedented erosion causes salt inundation far inland, and is a definite cause for concern.

Further north, Joseph Hullen (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāi Tūāhuriri) recalls a visit to Twizel in his school years. “One of the excursions was to Aoraki and to the Tasman Glacier. In those days, the terminal face of the glacier stopped just short of Lake Pūkaki,” he says. “During 2012, I was on a tahr survey in Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park with the Department of Conservation, flying around in a helicopter. Tasman Glacier now has Tasman Lake. So in that alpine environment we’ve seen the glacier melt and form a lake seven kilometres long, and that happened within 40 years. That’s the most outward expression of global warming or climate change to me.”

All interviewees unanimously stressed the importance of reinvigorating this mātauranga, especially considering rapid climate change. Now that a considerable number of weather and climate indicators have been identified, ground-truthing them may be the next step – fact-checking and validating data by going into the field – investigating “on the ground”. One way to do this could be approaching kura kaupapa and asking them to conduct research to verify the accuracy of the information we collected.

As we travelled around Te Waipounamu, it was easy to see and feel the pride that our whānau have for the knowledge that remains. It is a treasured taoka that connects them to their tūpuna. Hana Morgan explained to me the importance of upholding cultural practices and reconnecting to whenua. “The minute I’m back on the Tītī Islands it’s like … ‘I’m back! I’m home again’ … we think of our ancestors … they walked these tracks … we are not alone and you know that, and that’s why it’s so special.”

Unfortunately, we were also struck by the very real sense that this knowledge is in danger of being lost forever, as Maria Pera of Awarua told us.

“It is a constant struggle to keep this mātauraka alive, as more learned tākata mahika kai pass away.”

Tiny Metzger agrees. “It is hard to keep this knowledge alive if you’re not living it,” he says. As a lifelong muttonbirder, he can testify to the importance of upholding traditional practices.

Maria and Tiny liken this mātauranga to a tribal archive, slowly diminished with each passing.

The final words in this article were offered by a takata mahika kai from Wairewa, Aaron Rīwaka:

“Look after the land like you look after your children, and it will do its own work; it will grow itself. Look after our land.”

These treasured environmental indicators have been documented through this project to demonstrate how Ngāi Tahu whānau endured the vagaries of extreme weather phenomena on a daily basis. To help support and celebrate the notion of revitalising this special body of knowledge, a Ngāi Tahu weather and climate bilingual poster has been created. These posters and 36 video clips have been made available to honour this knowledge and to help restore it within the hearts and minds of Ngāi Tahu whānui. They can be viewed at:

http://www.deepsouthchallenge.co.nz/projects/forecasting-weather-and-climate-extremes.

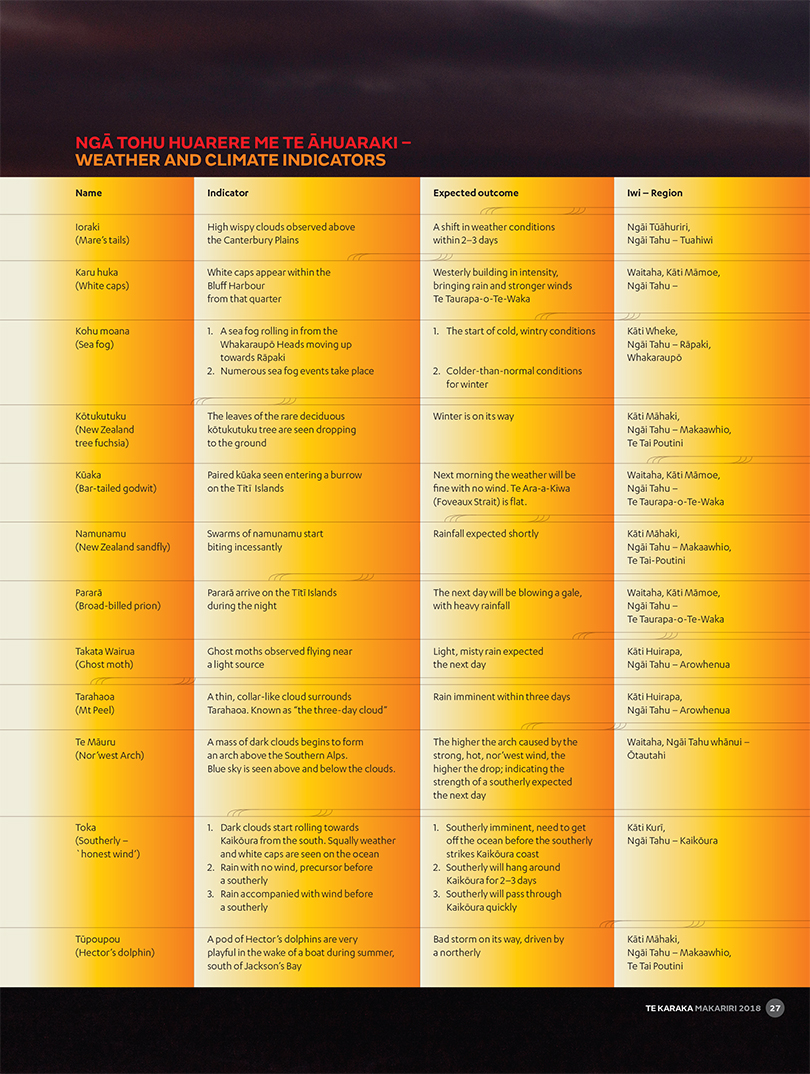

The table below illustrates some of the local environmental indicators traditionally used by Ngāi Tahu to manage activities linked with changes in weather and climate.

Acknowledgement: I offer my heartfelt thanks to all members of the research team, associated organisations and above all whānau members who participated in this research project.