Restoring kai sovereignty

Jul 7, 2016

Enterprise is thriving at Koukourārata thanks to the efforts of locals like Peter Ramsden and Manaia Cunningham, who are using traditional methods and science innovation to re-establish a thriving local kai-based economy.

Kaituhi Mark Revington reports.

Manaia Cunningham spreads his arms wide to encompass the harbour and surrounding land at Koukourārata on Banks Peninsula.

“This harbour has its own unique microclimate and gardening has always been in the whakapapa of this hapū,” says Manaia (Ngāti Irakehu, Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mutunga). “It doesn’t get much frost and has a long growing season. But for a long time, due to urbanisation and work centred around Christchurch, the gardens haven’t got the attention they deserve.”

We are standing up by the three pouwhenua, carved by Fayne and Caleb Robinson and installed by Te Rūnanga o Koukourārata with help from Ngāi Tahu Funds. They stand on a ridge that is the gateway to Kakanui Reserve overlooking the bay of Te Ara Whānui o Makawhiu. In carved form, Tautahi stands proudly on a plinth with his father Huikai and tupuna, Tūhaitara. Tautahi was the chief after whom Ōtautahi is named.

Manaia Cunningham.

In many ways the pou signify new growth at Koukourārata, growth that is a blend of innovation and tradition, extending from the rūnanga mussel farm to the māra kai or garden in the valley, along which extends a long stretch of riparian planting.

They are visual and spiritual markers which epitomise the philosophy of “food for the puku, food for the brain”, often uttered by Peter Ramsden (Ngāi Tahu , Rangitāne, Ngāti Raukawa), a chair and director of the Koukourārata Development Company, which is owned by the rūnanga.

Peter, the son of well-known journalist and author Eric Ramsden and brother of the late Irahāpeti, renowned as an anthropologist, a nurse, a publisher and an educator, embodies much of what is happening at Koukourārata.

Tautahi with his father Huikai and tupuna, Tūhaitara represented in pouwhenua carved by Caleb Robinson.

It seemed to start as a “grow off” between traditional Māori gardening practice versus the scientists from Lincoln University.

What has evolved is a burgeoning sense of commerce at Koukourārata, from growing blight-free organic taewa to setting up an aquaculture school, based on the rūnanga mussel farm.

Koukourārata was once the largest Māori settlement in Canterbury, with a population of around 400 in the mid-1800s. It has long been known as a food bowl, and was once famous for sending apples to the Chatham Islands.

“The first [programme] is the māra kai, an organic potato crop which will provide seed potatoes, eating potatoes, revenue, and jobs; and be marketed under the Koukourārata brand. The second is about establishing the taewa garden, and the third is an aquaculture and organic horticulture course using the new whare wānanga.”

Manaia Cunningham

Ngāti Irakehu, Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mutunga

“Koukourārata has always been proud of the sovereignty of our kai,” says Manaia. “We want to bring that sovereignty back.”

Taewa.

It is organic and has been tended with help from the Department of Corrections, which supplies workers through its periodic detention scheme. One innovation introduced at the behest of the rūnanga is certificates of accomplishment which recognise the work carried out by PD workers. Now, instead of spending hours at work in the gardens with little recognition apart from the feeling of having helped create a flourishing māra kai, they can achieve certificates through Lincoln University in organic gardening, chainsaw work, fencing, and driving quad bikes.

The intention was to grow the taewa at Koukourārata, says Peter. But no one had the necessary expertise for organic growing on a large-scale, so the rūnanga company forged a partnership with the Biological Husbandry Unit at Lincoln University.

This crop of taewa has been grown by the BHU at Lincoln, but the ground has already been prepared for a new crop at Koukourārata.

Dr Charles Merfield, Head of the Future Farming Centre at the BHU inspects the taewa crop.

“The whole intention was to do it at home, but none of us knew how to plough and how to grow on that scale,” says Peter. “But the intention is to move everything back home.”

Part of the preparation is to send a rōpū up north to visit Māori organic collectives, he says.

“It’s not about money, it’s about people. It’s about bringing people home in the right way, not about bringing them home and marginalising them. And it’s about the collective having goals. It’s all part of our success plan.”

Peter Ramsden Ngāi Tahu , Rangitāne, Ngāti Raukawa

These are all pieces of the Koukourārata puzzle envisaged by Peter for training and growing, and achieving work based around the marae – feeding the puku and the brain by growing food and providing training and jobs. They were established with help from Te Pūtahitanga, the Whānau Ora commissioning agency established by the nine iwi of Te Waipounamu, including Ngāi Tahu.

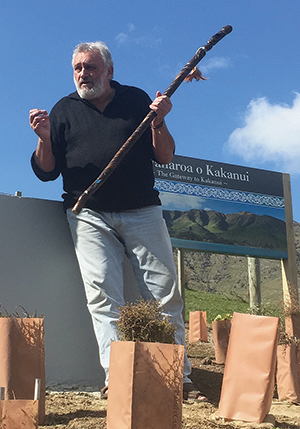

Peter Ramsden.

“The first is the māra kai, an organic potato crop which will provide seed potatoes, eating potatoes, revenue, and jobs; and be marketed under the Koukourārata brand. The second is about establishing the taewa garden, and the third is an aquaculture and organic horticulture course using the new whare wānanga.”

The rūnanga is having a whare wānanga built with help from Ngāi Tahu Funds as part of the marae complex, to serve as an outreach classroom for aquaculture certificates based on its mussel farm. They have also bought the old Le Bons Bay School, further along the coast, with plans to establish an environmental school.

Nothing is impossible, says Manaia. It is about good planning, a vision, and a will to succeed. The idea of a whare wānanga is crucial, he says. The new building will include an office, teaching space, a mattress room, and a walk-in chiller.

Aquaculture courses had been planned by the rūnanga before the Christchurch earthquakes changed everything, including the destruction of the offices in town where the rūnanga had planned to hold its courses.

“Last year we completed a strategic plan and four pou popped out: education, employment, business opportunities, and papakāinga. Everything we do is around those four pou.

“It’s not about money, it’s about people,” says Peter. Everything must have a process and solidity to it to be sustainable, but the greatest jewel of all is people.

“It’s about bringing people home in the right way, not about bringing them home and marginalising them. And it’s about the collective having goals. It’s all part of our success plan.”