150 Years Young

Jul 7, 2019

Nā Helen Brown

Around midday on Saturday 4 May a familiar sound echoed around the seaside kāika of Rāpaki on the shores of Whakaraupō. As has occurred for the past 150 years, the tolling bell was summoning Rāpaki whānau to church. A large group soon gathered outside the newly constructed fence surrounding the church and urupā. Among the familiar Ngāi Tahu faces were numerous members of the Couch whānau, at least two former Sunday School teachers, and officiating ministers and members of ngā hāhi katoa including Rātana, Katorika, Mihinare, Mōmona, and Weteriana. Āpotoro James Robinson conducted a whakawātea at the gates and led the worshippers up the shell-paved pathway into the recently refurbished church. Whānau members placed photographs of their tīpuna in the sanctuary beneath the restored triptych window in the west wall before settling into the old wooden pews, inscribed with their childhood graffiti, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Rāpaki Church.

“On Sundays we’d come running up from the beach in our bathing suits, and straight into church. You didn’t have to get dressed up. The old people were still alive, so you went to church whether you wanted to or not! We had different denominations. We’d have Anglican one week, Methodist one week. It wasn’t till later on we got Catholic as well.”

Herewini Banks

The quaint little weatherboard building with its picturesque views out to sea has been an integral part of the Rāpaki kāika since 1869, making it the oldest existing building in the bay. It is one of just a handful of 19th century weatherboard churches that have survived in our Ngāi Tahu villages to the present day. For the first hundred years of its history, the Rāpaki Church was central to the lives of local whānau who regularly attended services and Sunday School there. When the bell rang, you went to church! Latterly, services have taken place less often, although the church has remained an important community focus. In fact, Donald Couch suggests that at times, it has been a greater community focus than the marae. Archival lists of parishioners from the 19th and early 20th centuries reveal high attendance. “Virtually all the whānau went, it was a vital part of the community,” says Donald.

Above: Rāpaki Sunday School, c.1949. Left to right, back (from inside church door): Henry Couch, Kath Couch, Hineari Hutana, Josette Hutana, Lena Tikao. Middle: Miss Petrie, Nuki Tikao, Te Whe Hutana, Robert Tikao, Donald Couch, Gavin Couch. Front: Eddie Hutana, Peter Couch, Huia Couch, Maria Couch, Pam Couch, Billy Hutana (behind), Andy (?), Tony Tikao.

So, when the building began to show signs of deterioration due to weather and borer, Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke decided that it had to be saved. The timing of the conservation work coincided with the building’s 150th anniversary.

“On Sundays we’d come running up from the beach in our bathing suits, and straight into church. You didn’t have to get dressed up,” says Herewini Banks, who grew up at Rāpaki in the 1940s. Back then most of the families were regular churchgoers because, as Herewini says, “The old people were still alive, so you went to church whether you wanted to or not!

“We had different denominations. We’d have Anglican one week, Methodist one week. It wasn’t till later on we got Catholic as well.”

The non-denominational character of the church can be traced back to its earliest days, though it has always had a strong connection with the Wesleyan faith.

Above: Sunday School group, c.1959. Left to right: Diane McEvedy, Maria Couch, Ata Couch, June Watson, Elaine Rakena, Susie Rehu and an unidentified child.

In the days leading up to the 150th anniversary celebrations, Rewi Couch took a break from sanding down the church door to tell me more about the restoration project, his family’s connections to the church, and the influential Ngāti Kahungunu missionary who laid the foundation for the longstanding association between Rāpaki and the Hāhi Weteriana.

“Te Koti Te Rato was stationed here to mission to South Island Māori. His connection is really significant to Rāpaki. He married a Ngāi Tahu woman, my great-great-grandmother’s sister, Irihāpeti Mokiho. They had no children of their own, but whāngai’d lots of kids, including my great-grandfather, Teoti Rīwai.”

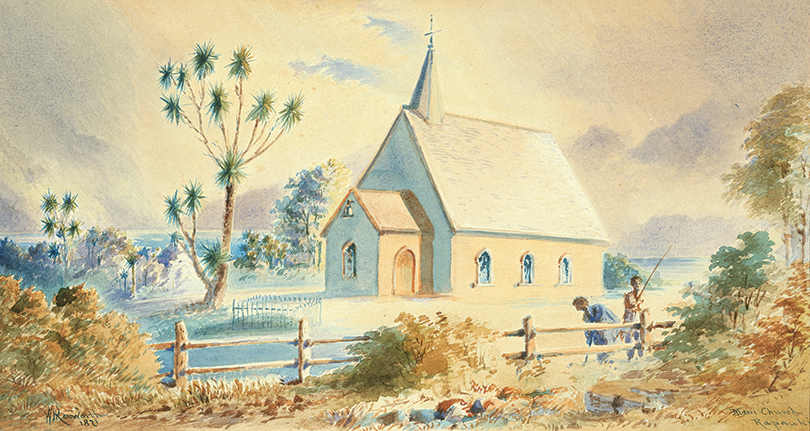

When Te Koti Te Rato arrived, the first Rāpaki church had recently burned down, but planning quickly ensued to construct a replacement. The necessary funds were raised from enterprises such as the sale of firewood to Lyttelton residents, and the church was completed and opened on 4 May 1869. It was built with hapū money, on hapū land, and remains in hapū ownership to this day.

The press reportage of the opening paints a familiar scene of the ecumenism that has come to characterise the Rāpaki Church. Wesleyan, Anglican, and Presbyterian ministers officiated at the service, which was conducted in both English and te reo Māori. The newspaper journalist commented that it was difficult to determine the denomination to which “the sacred structure” belonged. For more than 20 years, Te Koti Te Rato worked cooperatively with his Anglican missionary counterpart, James West Stack, based at Tuahiwi. In the spirit of collaboration, each administered to the other’s flock when one or the other was away on pastoral tour in distant parts of Te Waipounamu.

Talking with Rewi and other members of the Couch whānau, it is clear that church services at Rāpaki throughout the 20th century were very much a family affair. This was reflected in Dr Terry Ryan’s address to the congregation during the anniversary service, when he said, “I’m not sure who’s who, but you all look like Couches from here!”

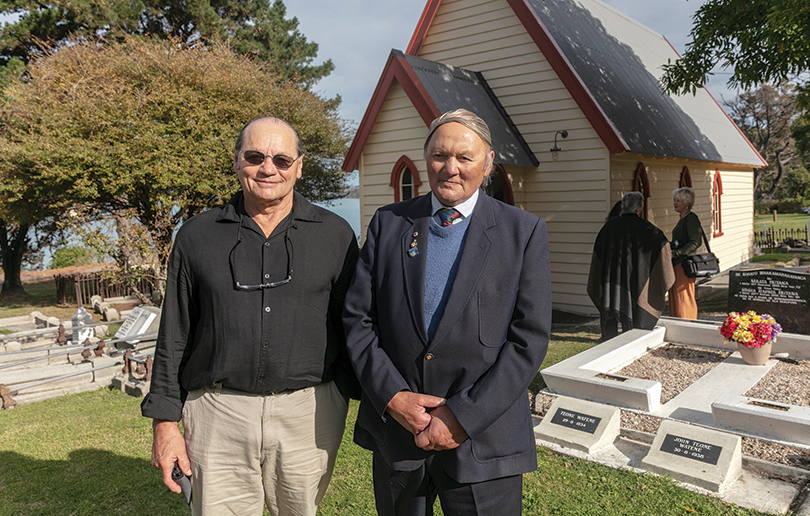

Above: Rewi Couch and Douglas Couch outside the church on the day of the 150th anniversary celebrations.

The Couch whānau has a deep, intergenerational association with the church that goes back to their tīpuna, George and Kiti Couch. George was an Englishman and lay preacher who regularly walked from Lyttelton to deliver services at Rāpaki in the 1880s and 1890s. His prospective wife, Kiti Paipeta, whom he later married, played the church harmonium. Later, Taua Kiti married two of her daughters to Wesleyan ministers. One of them, Sarah Mabel (May), married Rakena Piripi Rakena from Mangamuka, Northland. Their daughter, Elaine Dell, recalls that her mother was one of the key people who looked after the church in her day.

“She took responsibility for the church collections, which she kept in a big milk powder tin up in the top of her wardrobe. Uncle Arthur did the banking, and my mother always dusted the church and put flowers in it. On Sundays, they’d have the service and then go up to her house for a cup of tea.”

George and Kiti’s son Wera and several mokopuna including Lane Tauroa, Rua Rakena, and Moke Couch later became Methodist ministers. As Rewi recalls, “Uncle Wera was the minister, so there was this big extended family, and we were all part of it.”

When it came to the church’s restoration, it was very much a hapū affair, initiated and supported by the trustees of the church. Along with the professional builders and contractors, numerous members of the Rāpaki community were involved. Rewi, who oversaw the restoration project, says that by adhering to conservation best practice for heritage buildings, Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke has been able to tap into targeted heritage funding for the church that otherwise would not have been available. All of the work undertaken on the building was guided by a conservation plan written by local conservation architect, Tony Ussher.

Taking a conservation approach to the project has also ensured the retention of the patina of age in the building, such as the names etched into the back of the pews, reflecting the whakapapa of the people and the place. The church has been fully repainted, the entire west wall has been largely rebuilt, and the triptych window restored. The result is stunning. While 19th century austerity frowned upon ornamentation and few of our weatherboard churches from this period incorporate Māori arts and crafts, Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke is interested in the idea of adding some toi Māori elements to the church in the future.

Sitting in the sun outside the marae, Waitai Tikao confesses that he and his brothers and sisters would avoid going to church if they possibly could. “If our parents were attending, we had to accompany them,” he says. “We would spend the entire service looking longingly out the windows towards the sea – but if our parents weren’t there, we’d escape up the back road to freedom.”

Above: Rāpaki whānau and manuhiri responding to the call to prayer.

In addition to church on Sundays, the pā kids were expected to attend Sunday School (notable for being held on Saturdays). Waitai recounts an occasion the children were instructed to memorise a verse from the Bible – with apparent diligence, he thumbed through the pages and made a selection. At the next Sunday School class, he was a surprisingly eager participant. He stood up and announced that he would be reciting from the Gospel of John, Chapter 11, verse 35. “Jesus Wept”, he said, and promptly sat down. John 11:35 is famous for being the shortest verse in the Bible. Needless to say, he was not rewarded for his cleverness, but was instead required to memorise a second verse for recitation the following week. “They were pretty strict, and kept us in order,” Waitai says.

Former Sunday School teachers from the Brethren Fellowship, Diane McEvedy and Julian Burgess (née Pohio), were among the guests at the commemorations. Diane, who went on to become an Anglican priest, has fond memories of teaching Sunday School at Rāpaki in the late 1950s. “I really enjoyed coming over and engaging with the children and their families,” she says.

Following the sesquicentenary church service, a hākari for the several hundred guests culminated in the cutting of a suitably church-shaped cake. Kaumātua Uncle Doug Couch and Aunty Sal Rakena did the honours. The cake was made by Lynda Giles, whose mother, Barbara Smith, had made a comparable one for the Rāpaki Church centenary 50 years prior. Dr Terry Ryan, who was among those present at the 1969 celebrations, recalled that it had been a similarly memorable occasion. A commemorative church service was also held in 1994 to mark the church’s 125th anniversary.

As Donald Couch says, the Rāpaki Church “represents community and symbolises continuity.” Donald has written a history of the church to coincide with the anniversary. The book is dedicated to all those who have prayed in, preached at, and supported the Rāpaki Church. It is also dedicated to all those who died or were injured on 15 March, 2019 while praying at Christchurch mosques – a poignant and fitting whakaaro, given the spirit of inclusivity, cooperation, and ecumenism that the Rāpaki Church has embodied throughout its 150 year history.

Painting: Rāpaki Church, watercolour by William Henry Raworth, 1871, Alexander Turnbull Library, B-009-029.

The first Christian missionary presence in Te Waipounamu was Wesleyan, and came just after the release of our Ngāi Tahu prisoners of war by Ngāti Toa in 1839. Reverend James Watkin commenced the Wesleyan mission station at Waikouaiti in 1840, and soon established a network of contacts covering most of the Ngāi Tahu takiwā. Other denominations followed; notably Anglican, and Presbyterian under Reverend Wohlers on Ruapuke. As mission work progressed, almost all of our Ngāi Tahu kāika had one if not two (or even three) churches. Prior to the 1850s, most of these were simple raupō and slab style buildings, which had a life expectancy of about 20 years. At least one church of this early type predated the weatherboard church at Rāpaki.

The denominational rivalry which led to multiple church buildings in our villages abated somewhat in 1860 when Reverend James Buller of the Wesleyan Church and Bishop Henry Harper of the Anglican Church agreed to cooperate in their Māori mission work in the South Island. Under the “Harper-Buller understanding”, the two men agreed to the principle of “mutual occupancy” of churches where both denominations had functional congregations. This meant that when the early slab churches needed replacement, one substantial building could be erected to serve the needs of both denominations. The Rāpaki Church was one of at least 10 churches built in the Ngāi Tahu takiwā during this period.

While non-denominational, the church’s development was heavily influenced by the Wesleyan missionary Wiremu Te Koti Te Rato, who lived at Rāpaki from 1863–1891. Under his leadership, the Wesleyan Māori Mission in the South Island moved its headquarters from Otago to Rāpaki in 1865.