A growing tribal economy

Dec 19, 2017

Kēwai (keewai), a native freshwater crayfish, has a long history in the south, and was used in one of the earliest forms of aquaculture in Aotearoa – considerably pre-dating colonisation. A joint venture project between Hokonui Rūnanga and kōura farming business KEEWAI, with the support of the Tribal Economies team at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, is set to put these little creepy crawlies back on the map.

Kaituhi ARIELLE MONK reports.

There is a little-known kōrero about kēwai and south-ern Ngāi Tahu tūpuna.

Perhaps forgotten in anthropological and historical records, the kōrero is preserved and remembered by copses of tī kouka, scattered along ancient trails of the Murihiku region. Tī kouka (the cabbage tree), seemingly random in growth and placement, reveal a hidden wealth: flourishing populations of kēwai.

Such populations are evident around Glenorchy and up into the Cardrona River, indicating they may have been established by pounamu hunters.

Yes, the old people knew what they were doing.

The kōrero goes that ngā tūpuna would ferry live kēwai, or kōura (Paranephrops zealandicus), along the traditional travel routes around Otago, Southland, and even across to the West Coast. Strategic placement of the kōura allowed for a consistent, reliable food source along these long, often harsh trails.

John Hollows, aquaculture manager of the commercial kōura farming company KEEWAI, says this took place well before colonisation or European practices arrived.

“Without a doubt, they [Ngāi Tahu tūpuna] moved the kōura around and strategically populated areas along these trails. The iwi has a very strong historic connection to the kōura – it all points to New Zealand’s earliest form of aquaculture.

“They always could be certain they would have a feed on the way home from wherever they had travelled. It really was genius.”

This whakapapa of the relationship between Ngāi Tahu and freshwater kōura sets a beautiful foundation for one of the latest ventures to come out of Hokonui Rūnanga. Three months ago, after years of research, Hokonui released their first community of the creepy crawlies into a pond on rūnanga-owned land.

“It’s a good long-term investment for us. There’s very little uptake or work involved, because they feed themselves. And they’re all over the place for us – so if we can prove that we can grow them successfully, it could be a really good thing for Hokonui. And for other rūnanga too.”

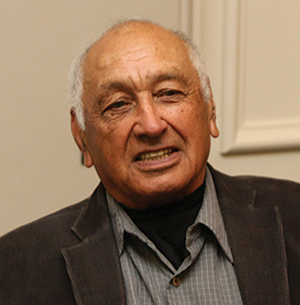

Rewi Anglem Hokonui Rūnanga kaumātua and executive member

In an initiative being guided by the Tribal Economies team at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, the rūnanga has partnered with KEEWAI to investigate the long-term benefits and potential revenue of freshwater kōura farming.

Rūnanga kaumātua and executive member Rewi Anglem is cautiously optimistic about the fledgling kēwai population.

Rūnanga kaumātua and executive member Rewi Anglem is cautiously optimistic about the fledgling kēwai population.

“It’s a long-term investment, definitely – right now, it’s about having them here on our land as a start. We’ve still got to go through our processes yet; but the project can grow as big as we want to make it really.

“For the release we had a bit of a get together, had a bit of a yarn. They [Ernslaw One Ltd, parent company of KEEWAI] brought in 100 breeders, 50 males and 50 females, and 15 berried females [females carrying eggs]. Each one has capability to breed about 80 babies. That’s 8000 kōura we could have.”

Rewi is a man with a modest and understated manner that belies the significance and excitement around the release. The Mayor of Gore and local media attended the introduction at Hokonui, as well as about 40 whānau members who turned out to see the kōura released into their new habitat. They are the first of the 18 rūnanga to take up the opportunity through a Tribal Economies development programme and partnership with KEEWAI and Ernslaw One Ltd.

Ernslaw One Ltd are the leaders in commercialising freshwater creepy crawlies in Aotearoa, although it must be acknowledged Ngai Tahu’s own Frances Diver was perhaps the first contemporary kēwai farmer. Thanks to his whanaunga connections to Central Otago, Rewi has familiarised himself with the species through Frances’ efforts in Alexandra.

Commercial investigation of kēwai began when Ernslaw One started exploring alternative revenue streams to bolster softwood exports after successive pricing downturns. As the fourth largest owner of forestry in the country, the chance to diversify was broad.

Some “bright spark” suggested freshwater crayfish farming as an additional venture for forestry land. Six years ago, the company employed John Hollows, armed with a Masters’ thesis on the effects of land-use on kōura, and a genuine soft spot for the nippers.

“It’s a bit of an experiment for Hokonui at this stage, but there’s huge possibility in the future. At the heart of it, it’s also about the rūnanga gaining an understanding of the biology of the kōura – it’s like any farming, really. You can’t farm an animal if you don’t understand its needs,” John says.

“You’ve got to think like a crayfish to understand them, so this endeavour is in part about getting whānau up to speed on what they need to provide the kōura with.”

And he isn’t joking about thinking like a crayfish, or understanding their needs – Rewi says he is used to hearing this kind of advice from John, the man who pets and kisses the creepy crawlies with real care.

And Ernslaw One Ltd has put their money where John’s mouth is – figuratively and literally. After six years as aquaculture manager, John has seen the project grow with approximately 2000 kōura ponds across 11 forests in Otago and Southland. KEEWAI is having measurable conservation benefits to the dwindling population of the native species.

“Hokonui has the ability to take it further with being more hands-on, because most of our sites are not so accessible,” John says. “But for the rūnanga, it is right in their back yard, and there are people on the marae all year round – providing an opportunity for them to familiarise themselves with the kōura.

“There’s a huge opportunity here for rūnanga specifically; whether it be utilising firefighting ponds in forestry blocks, or creating new ponds on land unsuitable for traditional farming purposes. You only have to fly up and down the country and see the number of ponds lying throughout forests to understand the potential revenue yield they could have through kēwai.”

Rangatahi Josh Aitken, 13, watches as Ernslaw One operations supervisor Callum Kyle talks about kōura at Hokonui.

The two native species of freshwater crayfish are rapidly declining due to the degradation of typical natural habitats, largely through chemical or storm-water drain pollution to waterways. John points to KEEWAI and the re-population of ponds across the Ngāi Tahu takiwā as a multi-purpose project, with benefits for mahinga kai mātauranga revitalisation, conservation efforts, and commercialisation – for Ngāi Tahu, but also for Aotearoa as a country.

“We’re now in our third harvest and have almost doubled quantity each year we have been in operation. We currently supply the market with about half a tonne, and there’s no reason to suggest this trend won’t continue,” John says.

To put that into perspective, the market demand has already has already outgrown the domestic supply, with high-profile clients like the Huka Lodge in Taupō vying for stock in the harvest season.

Robin MacIntosh is the Tribal Economies kaimahi assisting with the kēwai project from inside Te Rūnanga, and says the partnership between Ernslaw One Ltd, KEEWAI and Hokonui Rūnanga is a brilliant example of regional economic collaboration.

“Now, we are at the point of chasing stock to fill a two-year lag to meet known demand. It’s fairly certain that any future work with rūnanga farming kēwai will find markets to sell to.”

Rewi and the rūnanga have had a long time to assess the project for its value to Hokonui. Together with Tribal Economies, Hokonui has been investigating kēwai over a three-year pilot, which Rewi has been involved with since the start.

“We’ve been working with Robin and Tribal Economies for several years now. It’s been nice to have them on board, especially due to Robin being able to offer valuable advice.

“I think we would have been sort of lost if it wasn’t for them,” Rewi says.

The mihi aroha goes both ways. On taking the crucial leap from research and development to piloting breeding kēwai in rūnanga ponds, Robin is philosophical.

“Starting a new enterprise is always difficult; starting a new enterprise as a rūnanga, working with multiple projects and a voluntary labour force adds an extra challenge. To see that Hokonui has taken the step with their first pond shows a significant effort on their part, and a real determination to see such a long-term investment through.”

And although Rewi says it can be difficult for rūnanga based in the regions to retain rangatahi and younger leaders of the marae, he is confident Hokonui and the KEEWAI project will be in good hands. His understated nature comes back into play when the seasoned kaumātua considers the exciting implications of launching kēwai for the rūnanga.

“Well, it’s just another project you know? But it’s a good long-term investment for us. There’s very little uptake or work involved, because they feed themselves. And they’re all over the place for us – so if we can prove that we can grow them successfully, it could be a really good thing for Hokonui. And for other rūnanga too.

“They’re not bad eating either; unusual. It’s very fresh tasting, and good with a bit of salt – of course.”

Know your kōura

There are several species of crayfish/lobster called kōura:

Kēwai, southern kōura, South Island freshwater crayfish

(Paranephrops zealandica)

Paranephrops is a genus of freshwater crayfish found only in Aotearoa. The kēwai is found only in eastern and southern Te Waipounamu, and on Rakiura (Stewart Island). It favours colder water than its northern cousin, P. planifrons. Kēwai habitats include both native and exotic forests, in ponds and waterways in unpolluted conditions. Kēwai may be also be found in lower densities in clean pastoral streams.

Northern kōura, North Island freshwater crayfish

(Paranephrops planifrons)

This freshwater crayfish is mainly found in Te Ika a Māui, especially in lakes Te Arawa and Taupō. It is also found in Nelson, Marlborough, and Te Tai Poutini in Te Waipounamu. At about 70mm long, it is slightly smaller than the kēwai, and its pincers are less hairy.

Kōura, southern/red/spiny rock lobster, crayfish

(Jasus edwardsii)

This is the famed kōura of Kaikōura, and a distant relative of northern kōura and kēwai (southern kōura). It is found in coastal waters around New Zealand and offshore islands, and also Australia.

Kōura, packhorse lobster, eastern rock lobster

(Sagmariasus verreauxi, previously Jasus verreauxi)

A large, primitive rock lobster found only in the coastal waters of northern Aotearoa and eastern Australia.