Celebrating A Life Well Lived

Jul 21, 2022

In his 83 years, Tā Tipene O’Regan ONZ has been many things to many people. He is perhaps best known for his leadership of Ngāi Tahu in the final years of Te Kerēme, particularly during negotiations for the fisheries settlements of 1989 and 1992, and the Ngāi Tahu settlement of 1998. This year, Tā Tipene was awarded two of the highest honours our country offers; Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year, and appointed to the highest Royal Honour in the New Zealand system – the Order of New Zealand.

Over the years we have all become familiar with the public figure, and in honour of these milestones and a lifetime of achievements, kaituhi Anna Brankin sits down with Tā Tipene to learn more about his life – behind the scenes.

Above: Tā Tipene standing in front of “Te Manu o Te Ruakaupunga”, the first mural completed by the late Cliff Whiting ONZ (Te Whānau-ā-Āpanui) – gifted to Tipene in return for negotiating the sale of the great mural “Te Wehenga” to the National Library of New Zealand.

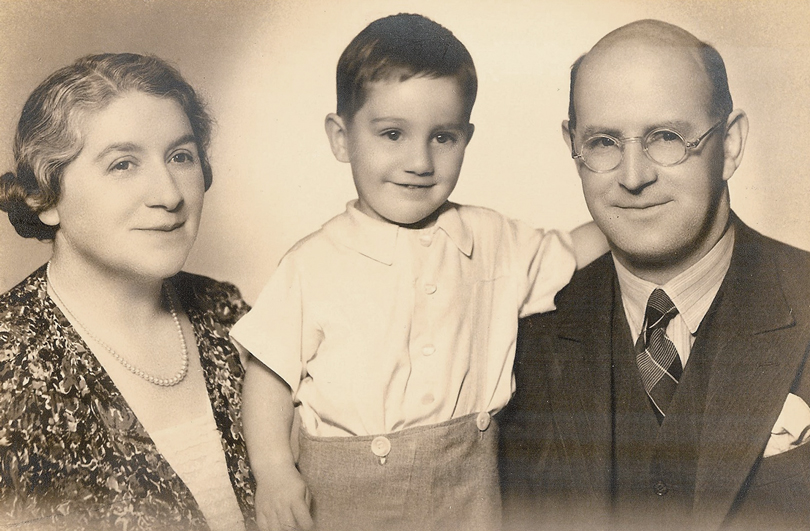

Stephen Gerard O’Regan entered the world in September 1939, the much longed for child of Rolland O’Regan and Rena Ruiha O’Regan (née Bradshaw). The couple met at Wellington Hospital where Rolland was a House Surgeon and Rena the first Sister in charge of the Casualty Department.

“The backstory is that my mother had nine pregnancies and I was the only live birth. The end result was that because of all the stress and trauma leading to my arrival, I was an object approaching veneration in my parents’ eyes,” he says.

Rolland and Rena Ruiha would go on to adopt two more children, Gabriel and Richard, but for the first six years Tipene was the only child in the house, and very much doted on. Some of his earliest memories are of waking up at night and seeing his father standing in the doorway, watching him sleep, and there was a running joke in the wider family that Rolland was always proudly sharing the exploits of “my boy Steve.”

Much like his own father, Rolland was a polymath, extremely intelligent with a broad range of interests. Tā Tipene recalls that he “read with avidity, and was deeply interested in native plants and birds. He was the senior vice-president of Forest and Bird, a vice-president of the Labour Party, and led a successful campaign to convert the Catholic Church from the use of Latin to English, the language of the population, although he was fluent in Latin himself and like his elder brother, read Latin text for pleasure.”

On the other hand, Tā Tipene remembers his mother for her warm and gracious air. “My mother Rena was a woman of considerable charisma. She was one of those people who could walk into a room, and she wouldn’t do anything except smile, but everyone knew she was there,” he says. “She had a particular gift for gracious behaviour.”

Above: A young Tipene with parents Rena Ruiha and Rolland.

He recalls when he was young the great Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck) was on a return visit to New Zealand and staying in their family home. The Ngāi Tahu kaumātua Te Aritaua Pitama travelled to Wellington to meet Sir Peter. “My mother welcomed him in to our sitting room, sat him down at one end of the room and seated herself adjacent to Te Rangi Hīroa at the other end. Anyhow, the clear point was that Te Aritaua Pitama needed to be welcomed, and I can remember my mother turn and with considerable grace just say, ‘Peter?’ and Te Rangi Hīroa stood up and mihied to him, and Te Aritaua got up and replied. They sat down and the conversation got underway.

“It’s a memory I have of the way in which my mother just looked across and with a gentle word, Te Rangi Hīroa, this famous man, obediently stood up and did what was required. In my memory it is the first formal whaikōrero. My other memory of that day was the beautiful euphony of Te Aritaua’s voice – in English and in te reo – it was like a magnet!”

Tā Tipene credits his father for his own broad range of intellectual interests, and his mother for his more emotional side. He describes the couple as loving and kind towards each other, saying: “My mother’s only ambition for me – apart from that I should be moderately happy and so on – was that I should make my father proud. She died in her mid-60s, but they were still going for walks together. That is another memory: seeing them going for a bit of a stroll, just simply walking along holding hands.”

His father was very interested in his boy Steve’s development, and there are lots of memories of spontaneous quizzes, debates over the dining room table, and learning opportunities found everywhere. “He’d take me away on journeys and every so often he’d pause the old Chevrolet and say ‘look at that particular tree’ or ‘look at the way that hill’s shaped’ or ‘where do you think the tide’s running here?’” Tā Tipene recalls. “When we went hiking, I used to have to carry three books in my backpack. Dad would carry the lunch.”

This strategy evidently worked, as Rolland became known to say: “Getting that boy past a bookshop is like getting an alky past a pub,” and to this day Tā Tipene says “home is where my books are.”

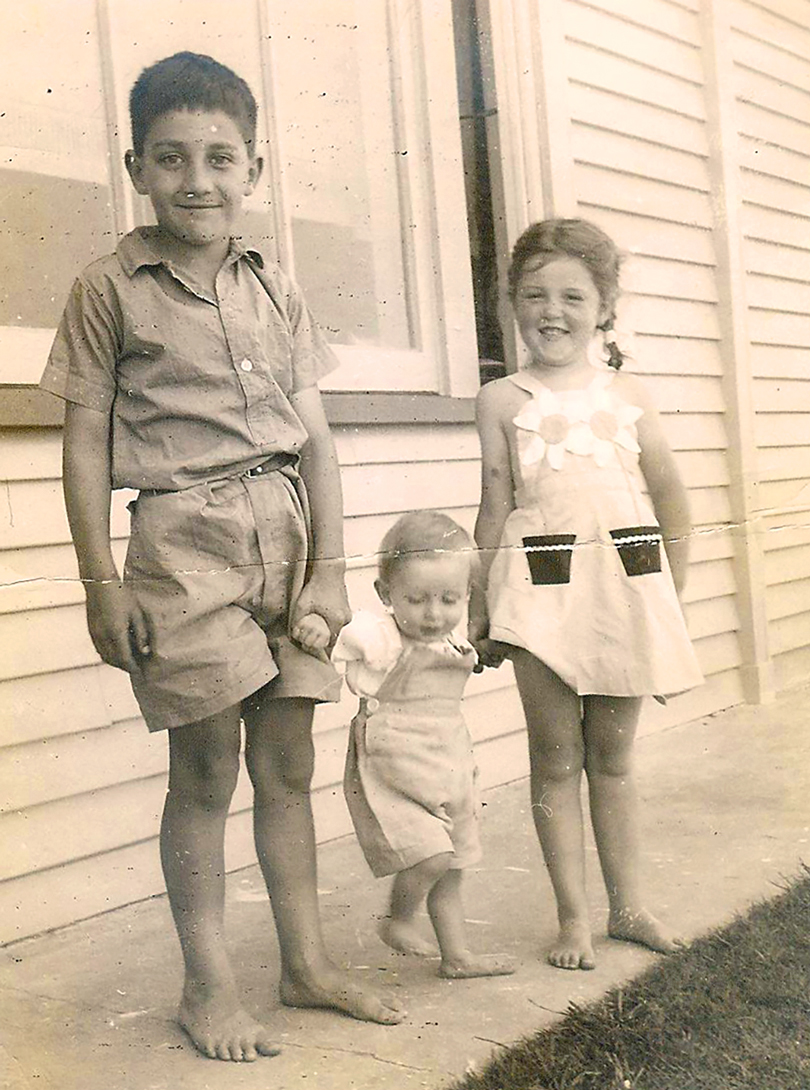

Above: Tipene aged about 7 or 8 with Richard and Gabriel.

Besides reading, the young Tipene developed a fascination with boats – a passion that has never left him. To begin with, there was a space set aside in the basement for him to work on his model boats, and as he got older he took over a shed at the bottom of the property as his workshop.

“I inherited a fair bit of this from my father, who had a very old friend who was a marine engineer with a famous old black painted yacht called the Viking. She was about 40 feet and clipper bowed, and sailing her on a windy day was a bit like sailing in a half-tied rock, but I thought she was just gorgeous,” he says.

“She was moored off the old Hātaitai Bathing Club area and I’d go down there and swim with my friends and look out across the bay at the little black Viking. I’d borrow a dinghy and I’d spend the day rowing around with my mates, from boat to boat – looking at boats, studying boats, arguing, talking about them.”

The obsession was such that Tipene as a teenager developed the notion that he would end up going to sea, one way or another. However, when he finished high school he enrolled at Victoria University, saying he knew it was expected of him. “I did genuinely think I wanted to be a lawyer, and enrolled in a BA LLB and strangely enough after a triumphant first year I went off the boil academically. I failed English One, I think, three times.”

This was in keeping with a pattern established early in life, in which he would simply lose interest in subjects that didn’t engage him.

“I had that experience at secondary school too. I kept failing all sorts of things because I wasn’t interested in them, but the things I was interested in, and with teachers who did stimulate me, I responded very well to.”

“I can still remember my first sight of Australia as we approached Wilsons Promontory on the south-east corner of Bass Strait. It had a powerful effect on me, that first time I saw a foreign land.”

His time as an ordinary seaman continued when he was assigned to work on the inter-island ferry Māori, sailing between Wellington and Lyttelton. Eventually he signed off and came ashore, and was studying part-time and working in the parliamentary library as a reference librarian when he first met Sandra McTaggart, a trainee economist. It was not exactly love at first sight, with Tipene recalling that Sandra “wouldn’t have a bar of him” to begin with … “I pursued her and she kept giving me rubbish arguments. It’s a convoluted story and all I can say is that by February 1963 we were married.”

During his short-lived time at university, Tipene spent his holidays working in Fiordland as a deckhand on tourist boats and once as a guide for the packhorse that took supplies up from Sandfly Creek at Milford to the Quintin Huts. “I’d load up the packhorse in the morning, the packhorse knew the way perfectly well, and by the time I buggered around and wandered up the first leg of the track, the horse would be happily grazing away and I’d unload it and have a cup of tea with the cook, and I’d wander my way back down to Sandfly Creek.”

He describes these stints as very useful and interesting experiences, and the beginning of a love for the Fiordland region that he would continue to explore recreationally and through his work.

Above: The obsession with sailboats started early.

Back in Wellington, it was evident that his efforts at university were not going to be fruitful. “I gave it all away one morning, I walked into the Seamen’s Union office and introduced myself to Finton Patrick Walsh, the President. I introduced myself to Walsh on the basis that I was “Big Pat O’Regan’s” grandson and told him that I wanted to go to sea. I was cleary too old to be a deckboy and I expounded on my experience with Navy Sea Cadets and small boats and various other things. Againist all the rules, Walsh put me on the Union’s books as a ‘Bucko’ – an Ordinary Seaman.”

Finally, Tipene had realised his dream and gone to sea, on a ship bound for South Australia to bring back wheat. His duties included everything from polishing brass to setting tables in the seamen’s mess, and after the captain and first mate took a shine to him, he worked on bridge maintenance and keeping things in order in the chart house.

“I can still remember my first sight of Australia as we approached Wilsons Promontory on the south-east corner of Bass Strait,” he recalls. “It had a powerful effect on me, that first time I saw a foreign land.”

His time as an ordinary seaman continued when he was assigned to work on the inter-island ferry Māori, sailing between Wellington and Lyttelton. Eventually he signed off and came ashore, and was studying part-time and working in the parliamentary library as a reference librarian when he first met Sandra McTaggart, a trainee economist.

It was not exactly love at first sight, with Tipene recalling that Sandra “wouldn’t have a bar of him” to begin with. “When we first met I was lending moral and physical support to a lamp-post outside Barrett’s Hotel,” he says dryly. “I pursued her and she kept giving me rubbish arguments. It’s a convoluted story and all I can say is that by February 1963 we were married.”

As part of their wedding present, Rolland and Rena gave the young couple the use of the flat beneath the family home for the first year. Tipene returned to university to finish his degree, and Sandra continued her work at Industries and Commerce before they had their first child, Rena, at the end of 1963.

At this point their plan was to emigrate to Tasmania, where Tipene had a job waiting and a plan to build the boat they’d then sail to the Caribbean so he could realise his dream of becoming a charter skipper. They were meant o be leaving in January 1964, but just before Christmas 1963 they received a telegram saying their passage had been rerouted. Unable to get another booking for nearly a year, the young couple were at a loss.

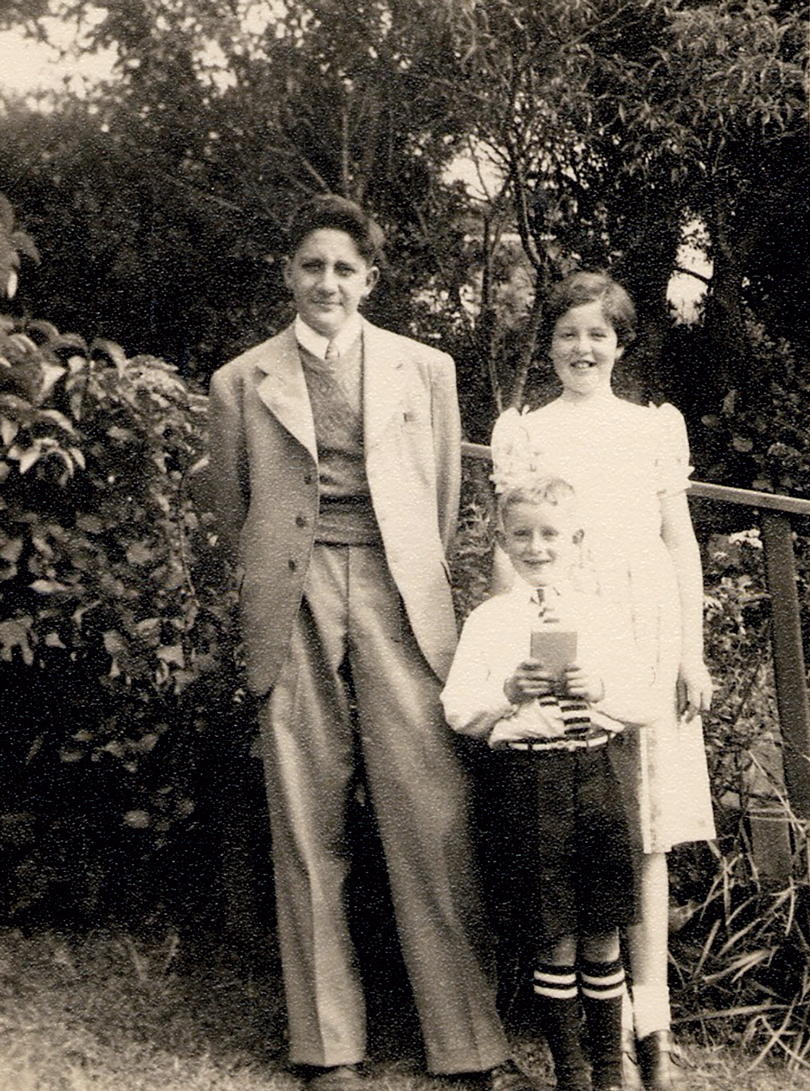

Above: Tipene as a teenager with his sister Gabriel and brother Richard – in what he believes was his first suit.

It was around this time that Rolland ran into Walter Scott, a family friend and the principal of Wellington Teachers’ Training College. When Walter asked after Tipene, Rolland told him his son was married with a young baby, didn’t have a proper job, and his plan to take off to Australia had just fallen through.

Walter arranged for Tipene and Sandra to enrol in teachers’ college, and they began classes the next day while baby Rena stayed at home with her namesake, her taua – Rena Ruiha.

“So that’s how I became an educationalist, because my father met someone in a lift and a boat didn’t come,” Tā Tipene laughs.

He went on to teach at primary school for two years, before being invited back to Wellington Teachers’ Training College as a lecturer in 1968, a role he would hold until 1983.

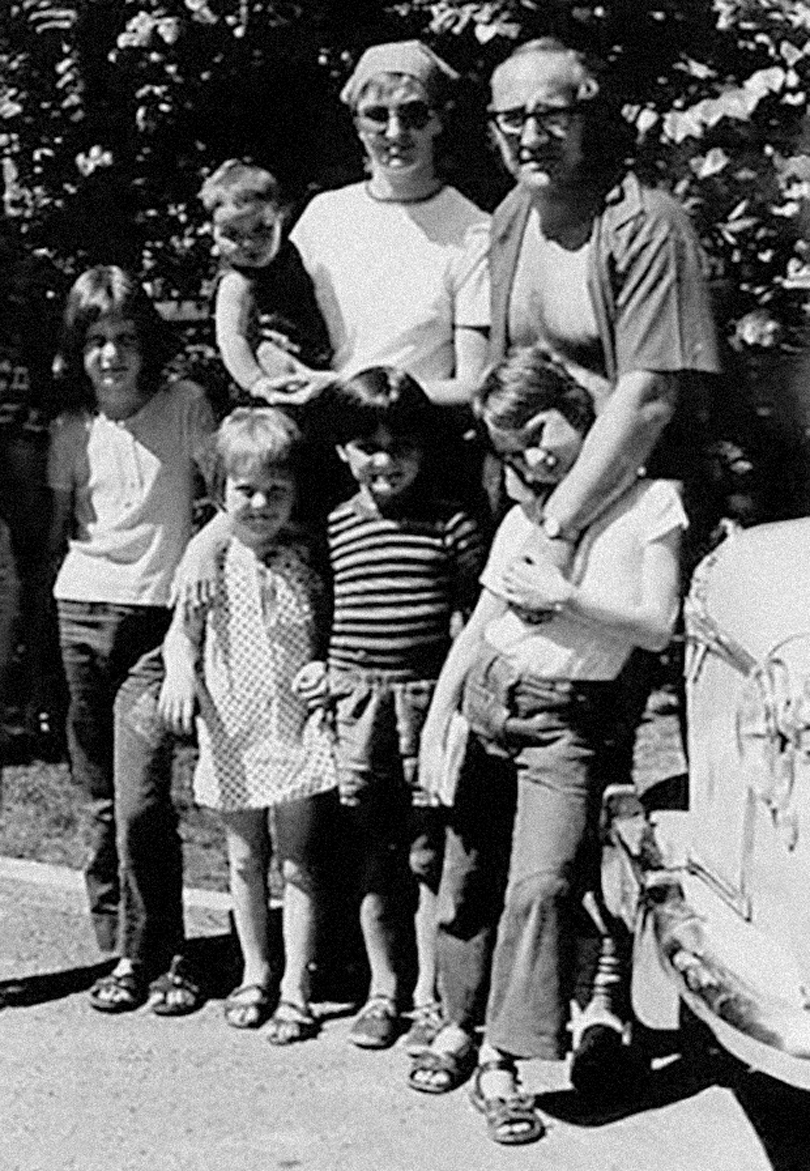

During these years they had four more children: Gerard, Taone, Miria, and Hana. It was also when Tā Tipene’s work for the iwi began in earnest, resulting in a busy time for the young O’Regan whānau.

Growing up, Tipene had always maintained a strong connection to his Ngāi Tahu whakapapa by virtue of his close relationship with his taua, Rena Bradshaw, who lived in Bluff but often travelled around Te Waipounamu and Wellington. “I’d be sent off to Bluff during school holidays, and because she was of an age when she was going around visiting the relations on a regular basis, I’d be sent to join up with her then,” Tipene says. “My father became my taua’s favourite go-to guy. She was the keeper of Te Kerēme in our whānau, and he would write articles for her and advise her on different matters to do with her interest in the Ngāi Tahu claim.”

Although Rolland was Pākehā, he had a powerful sense of social justice and was hugely supportive of his wife’s iwi. Between the many dinner table debates on the topic, and the time spent with his taua and Ngāi Tahu relatives, Tipene was always very familiar with the grievances of the iwi and the aspiration to receive some sort of reparation from the Crown. When the call came for him to take a more active role in 1976, he was already primed.

“We had just sold our house in Paekākāriki and moved into the city when I got a phone call one night from Frank Winter, chairman of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board, asking me to go over and see him. I didn’t know it at the time but I learnt later he had had an eye on me for some time.”

Above: Tipene, Sandra holding Hana, Rena, Miria, Gerard and Taone – Wellington 1974.

The young Tipene had first come to Frank’s attention during his time at Victoria University. Frank and his wife were patrons of the Victoria University Māori Club. And in 1959, Tipene and a few of his friends were involved in the Citizens All Black Tour Association (CABTA) with his father, Rolland, being the Chairman of the nation-wide protest. Tipene marched in protest of the non-selection of Māori players for the South African tour of 1960. A prominent member of CABTA, Frank evidently made a note of the bright young Tipene and years later as his health declined, he reached out.

“He told me that he wanted me to succeed him as the Te Ika a Māui member of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board,” Tā Tipene says. “By that time I had become interested in Ngāi Tahu traditional history, Polynesian migrations, New Zealand history, and all of this was coming to a head when Frank told me of his ambitions for me, and I didn’t want to have a bar of it.”

Although he was reluctant to take over Frank’s position, Tipene continued to visit him. “Every time I visited him he’d lend me a whakapapa book, which I’d go home and transcribe, and he’d give me another one, and in this way I was reeled in like a bloody fish.”

During these years Sandra continued to work and support their growing family, meaning Tipene often had children in tow on his trips around Te Waipounamu, allowing him to continue the tradition his own father had started with him, and share his interests and knowledge. Years later, his fascination with oral history came into focus when his daughter, Rena, by then studying anthropology and classics at university, asked him to give a guest lecture.

“She’d been exploring the theories of oral histories and the oral transmission of myths, and she said, ‘I’ve realised that’s what I’ve been doing all my childhood, travelling in the car with you’. I had to go and look it up and see what the hell oral history was, and I realised what she was saying to me about the nature of myth and the character of oral history, and that started me off on the meaning of place names and all these sorts of things.”

On one such visit all members of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board were there, having come to say farewell to Frank. The result of this impromptu hui was that Tipene agreed to take the seat on an interim basis, with a permanent replacement to be appointed at the next election – for which he didn’t intend to be available.

“Frank had a wee smile on his face when I left, and 45 minutes later he died and a whole new chapter was opened.”

This marked the beginning of a period in which Tā Tipene describes himself as being “very much on the move.”

“The nickname they had for me in those days was ‘takata haere pō’ – the man that travels at night,” he says. “I’d take the car, I’d go on the ferry, I’d pick up Rangi Solomon at Ōaro and come on to Christchurch, and I’d bring him back the next day as I travelled north.”

During these years Sandra continued to work and support their growing family, meaning Tipene often had children in tow on his trips around Te Waipounamu, allowing him to continue the tradition his own father had started with him, and share his interests and knowledge. Years later, his fascination with oral history came into focus when his daughter, Rena, by then studying anthropology and classics at university, asked him to give a guest lecture.

“She’d been exploring the theories of oral histories and the oral transmission of myths, and she said, ‘I’ve realised that’s what I’ve been doing all my childhood, travelling in the car with you’,” Tā Tipene says. “I had to go and look it up and see what the hell oral history was, and I realised what she was saying to me about the nature of myth and the character of oral history, and that started me off on the meaning of place names and all these sorts of things.”

As a result of this newfound interest, Tā Tipene would continue as a guest lecturer in the classics department for many years, as well as spending more than 30 years on the New Zealand Geographic Board.

Above: Sandra and Tipene – “all dolled up” for a Government House dinner – early 1990s.

Similarly, his road trips with Rangi Solomon provided their own source of inspiration, because that was when Tipene learned about the Ōaro papers and started thinking about the huge wealth of knowledge that Ngāi Tahu whānau had in their possession. “That really got me started on my ambitions for the Ngāi Tahu Archive, which I founded in 1978.”

When he wasn’t travelling, the O’Regan family home became the central Wellington base for Ngāi Tahu.

“Ministers, cabinet ministers, politicians, even embassy people, occasionally, all were ordinary in our house. Sunday night was frequently busy, writing notes for cabinet ministers the following morning.”

Tā Tipene recalls then Minister for Māori Affairs, Koro Wētere, would often call him, asking for help with a cabinet paper. “I’d say ‘I presume this is for tomorrow morning Koro?’ and he’d say ‘yes, just a one-pager.’ Writing one page on a complex subject became my capacity.”

It was around this time that Tā Tipene O’Regan became something of a public figure, brought to his attention when then Prime Minister Robert Muldoon’s response to the prospect of a settlement with Ngāi Tahu was: “This country’s not going to be held to ransom by a cunning part-Māori.”

“I had several public debates with him which got quite a lot of media attention, but it took a while for me to realise that other people were bothering with what I said or did,” Tā Tipene says. It was driven home in 1994, when he was knighted for his services to Māori and the community.

Renowned for his written and oratorical skills, Tā Tipene says these evolved naturally. “I’m nothing like as polymathic as my father or my grandfather, but I do have a capacity for seeing relationships within things,” he reflects. “Often someone will ask me a question and in answering it I’ll take them out and around through all different topics, and then I bring them back to a point right at the heart of it. And my gift for metaphor I inherit from my mother. I’ve escaped many a difficult corner with a good metaphor.”

It goes without saying that Tā Tipene has made an immense contribution to the wellbeing and prosperity of Ngāi Tahu, and his work on behalf of the iwi has continued for more than two decades after the settlements for which he is most well-known.

“Just as my father always said I never had a proper job, I’ve never really retired,” he says. After living in Wellington their whole lives, Tipene and Sandra moved to Ōtautahi in 2008, allowing them greater opportunity to explore their favourite places: their house – and Tā Tipene’s beloved boat – at Waikawa; the West Coast, where both their families hail from; and Te Rau Aroha, the marae at Awarua.

As Tā Tipene reflects on a very full life, he’s grateful for the many opportunities he’s had – the places he’s visited, the people he’s met, and the progress he’s been able to contribute to. When asked to describe his most memorable experiences, he is reminded of little snapshots in time, moments of peace and beauty that brought him joy.

“Some of my most enduring memories have occurred in quiet bays and nice corners of the Marlborough Sounds, with the morning chorus or evening chorus of birdlife,” he says. “Or once, when I was on a schooner called the Queen Charlotte and we were surrounded by dolphins in the golden evening light. I saw a dolphin come up and dive through the triangle made by the bowsprit and the bobstay and I was just filled with wonder at the symmetry, the beauty, the whole thing.”

“I’ve negotiated some pretty heavy stuff over those years but negotiating a successful outcome of five children, 13 mokopuna and three mokopunanui has to be the best thing I’ve done, after marriage to their mother and grandmother. There has been quite a lot of academic success, which is important but not central.

What is really important is we come together most Sundays wherever we are in the world on Zoom and we all still seem to like talking to each other and valuing our love of each other, that is the richest gift of all.”

Tā Tipene shares other moments: visiting Kāpiti Island with his father and seeing weka and kākā for the first time; hiking the Murchison Ranges in Fiordland to see the takahē after they were rediscovered in 1948; standing on board HMNZS Otago just off subantarctic islands The Snares and watching kororā slide down the cliff into the sea, sharks lying in wait and skua gulls circling to clean up the scraps. That night he saw the survivors return and scramble their way up the same cliff to their burrows.

“You see a thing like that once in your life and remember it forever. It’s things like that that stay with me,” he says. “I’ve even had it quite recently as we flew out of Whenua Hou in the chopper. Looking at the late afternoon sun on the Rakiura cliffs as we approached – that’s stuck in my mind, that view.”

Notwithstanding the cherished memories of place, of coastal and ocean voyages and memorable anchorages, it is whānau based on nearly 60 years of marriage to Sandra that stands at the centre of his heart and mind. “I’ve negotiated some pretty heavy stuff over those years but negotiating a successful outcome of five children, 13 mokopuna and three mokopunanui has to be the best thing I’ve done, after marriage to their mother and grandmother. There has been quite a lot of academic success, which is important but not central. What is really important is we come together most Sundays wherever we are in the world on Zoom and we all still seem to like talking to each other and valuing our love of each other, that is the richest gift of all.”

When Tā Tipene O’Regan received the accolades of Kiwibank New Zealander of the Year in April, and appointment to the Order of New Zealand in June, he says he was “surprised by joy.”

“I didn’t have any expectations that it was coming, and it caught me by surprise,” he says. “I felt too happy about the accolade to be in the least bit humble about it, and I feel enormously honoured to have ONZ after my name.”