He Aitaka A TāneTutu is toxic but a taonga

Dec 4, 2012

nā Rob Tipa

If there is one plant you would not expect to find in Ngāi Tahu’s taonga species list, it is tutu.

Photo courtesy of Steve Attwood ® 2010

Tutu carries the dubious distinction of being this country’s most toxic plant, historically responsible for many deaths of adults and inquisitive children, perhaps attracted by its shiny black berries.

Tutu is also responsible for more stock deaths than any other plant in Aotearoa, with livestock losses of between 25 and 75% for early runholders when the plant was more common than it is today.

Most of the plant’s parts are poisonous, containing the neurotoxin tutin that attacks the nervous and musculatory systems of its victims. A dose of just one milligram is sufficient to cause severe nausea, vomiting and lassitude in a healthy adult.

Even today, sporadic outbreaks of toxic tutin honey are reported around the country when bees feed on honeydew exuded by a sap-sucking vine hopper that feeds on the tutu plant.

Botanically speaking, several species of tutu (Coriaria spp.) are commonly found throughout New Zealand in scrub, along forest margins and on roadsides from sea level up to an altitude of 1100 metres.

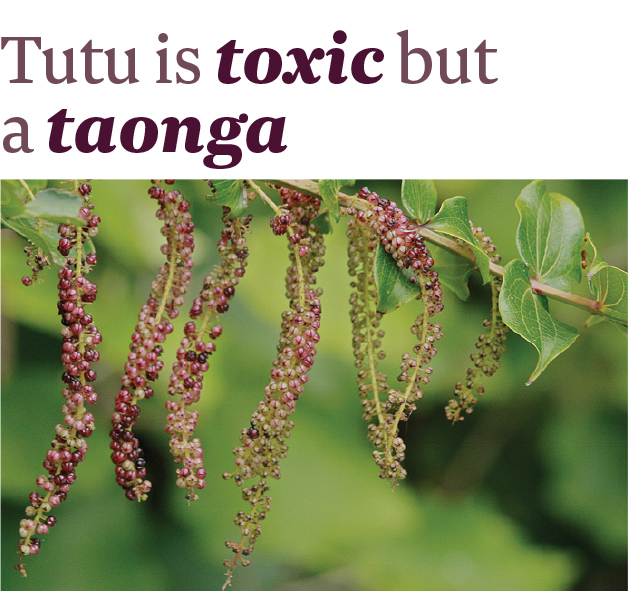

Its flowers hang on stems up to 30cm long like strings of black currants, from September through to February. Its shiny black fruits ripen from November through to April.

Its fleshy foliage and young shoots are particularly attractive to livestock in spring. Some reports suggest stock with a full stomach may be lucky to survive the ordeal, but for those that eat tutu on an empty stomach the result is usually death.

Plant poisons were not common in southern parts of Aotearoa, but for early Māori, rori te tutu (tutu poisoning) was treated as seriously as karaka poisoning. In those days the treatments for poisoning with either of these plants were almost as violent as the poison itself.

If a person accidently swallowed tutu seeds, the poison distorted their face and cramped their jaw. A stick or rag was placed between their teeth to prevent them biting their tongue until they started frothing at the mouth and vomited up the seeds.

An old Māori remedy involved hanging the victim upside down over a smoky fire to induce vomiting, sometimes with the help of some vile brew like the water of boiled pūhā to hasten the act.

The victim may have been forced to take a steam bath or a compulsory run to make them sweat out the poison. There are also reports of tutu victims being held in cold water long enough to stop their blood circulation, or buried in sand to stop the convulsions – a treatment also used for karaka poisoning. No doubt anyone who survived such rough treatment would be grateful to get away with their lives.

And yet reference books are full of detailed descriptions of tutu’s uses by Māori as a refreshing drink, jelly and sweetener of foods. It was also used in various recipes for treating illnesses and injuries, and as an indelible ink used in tattooing.

However, preparation of these recipes was often tricky, so the plant was naturally treated with considerable caution by both Māori and Pākehā.

As Murdoch Riley explains in Māori Healing and Herbal, “all parts of all species of tutu from their leaves to their roots have some toxic content, except for the juice of the ripe berry, or more precisely the juice of the enfolding petals of the berry.”

Tutu juice, known as wai pūhou, was a refreshing drink made from the dark purple juice extracted from the fleshy petals. This juice was used to sweeten various foods such as aruhe (bracken fern root), but it had to be scrupulously strained and filtered through toetoe or raupō flower heads to ensure that none of the poisonous seeds slipped through.

Visitors to a kaika could tell by the colour and taste of the juice whether it had been freshly prepared. It was an insult to offer wai pūhou that had stood too long, as the taste was sharp or sour, and the brew had an intoxicating effect.

Tutu juice could also be boiled with a type of seaweed known as rehia to produce a jelly that was eaten cold.

European missionaries and settlers made their own fermented wine from tutu berries, which was apparently similar to elderberry wine or a light claret. By all accounts, it was “very palatable and particularly potent.” This was presumably a reference to its alcoholic properties, rather than its potency as a poison.

History records plenty of instances where people have died or suffered serious illness when they have not been meticulous in their preparations of tutu juice, beer or wine; particularly to remove the highly poisonous seeds from the liquid.

Juice of the tutu plant stains the skin brown, so in early times young warriors who had not yet been tattooed used this plant to mark their faces before battle.

Māori used the soot from burning tutu wood mixed with oils from weka, shark or tree oils to manufacture an indelible ink for tattooing, and also extracted a red or black dye from the bark. Early European settlers developed their own recipe for ink by mixing tutu juice with gunpowder.

Historical records show Māori had numerous medicinal uses for tutu, and Riley dedicates five full pages of his ethnobotanical reference book to record these in considerable detail.

The juice extracted from tutu flower petals was used as a laxative.

Various preparations of tutu leaves and shoots were used to dress wounds and bruises, set broken bones or sprained ankles and to make an antiseptic lotion to treat cuts and sores.

Ma-uru was a patent medicine made from the tutu root that was strongly recommended by some early Europeans to treat neuralgia, headaches, chilblains, rheumatism and eye strain.

For the musically inclined, the kōauau (flute) with three holes and the pōrutu,a large flute, more like a European flute, with four to six holes, were both made from tutu rākau, a larger species of tutu that grew into a tree.

Considering its ruthless reputation for any error in preparation, it’s a wonder our tupuna risked their lives to find so many uses for this taonga plant.