Only natural

Apr 5, 2015

As he prepares to retire from his role as Professor of Māori Art and Design at Massey University’s College of Creative Arts, Ross Hemera tells kaituhi Moerangi Vercoe why ancestral rock drawings have made such a lasting impact on his art.

It’s a well-grounded childhood that Ross Hemera, now 65, recalls fondly. Good times, with five younger siblings, Mum and Dad, Ruth and Boko, who liked to take them all on little adventures.

“Dad would take us on day fishing trips and those trips were down the Ahuriri River, just a few kilometres from where we lived.

“I recall an introduction to those drawings along the Ahuriri River. The drawings we looked at are still really vivid to me. We had drawing paper and pencils and we sat there and copied them.

“But,” says Ross with a wry smile, “to put it in context, Dad loved fishing. He was good at catching fish and eels. So he would set us up in the shelters with our pencils and pads, and then he would go off and fish for hours. Kind of like a little kāinga – he left us in these places and he knew we would be there when he returned.

“Although he was not a scholar I think it was because of his southern Ngāi Tahu upbringing and his own appreciation of history that he showed us the drawings.

“I recall an introduction (from Dad) to those drawings along the Ahuriri River. The drawings we looked at are still really vivid to me. We had drawing paper and pencils and we sat there and copied them.”

“He was creative and a bit of an artist and good craftsman, and he could make anything. I remember him taking us fishing one day down to the beach at Kakanui. We were on the beach in the rocks and there were big pieces of bull kelp, and he made us shoes out of the bull kelp so we could wear them on the rocks and not hurt our feet. He knew how to do things like that.”

With some of the rock art sites of his childhood now submerged by the Benmore Dam, Ross is thankful for the opportunity he had to make hand drawn copies of them. He still cherishes those childhood drawings.

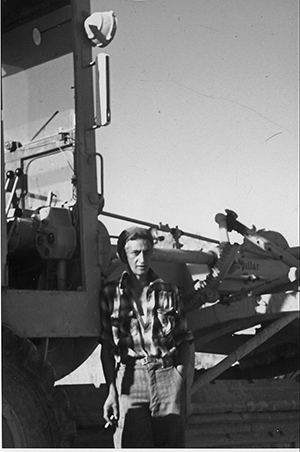

Above: Ross Hemera’s father, Boko.

His dad is an influence Ross clearly treasures deeply. Boko’s father Tura Hemera, from Kahungunu ki Wairarapa, had disappeared from Boko’s life quite early. Boko’s mother Maggie had died when he was young. Boko and his sister were raised by their grandmother at Colac Bay, until the two young children became too difficult for her. They were put into state care with the Haberfield family. His great grandmother on his Ngāi Tahu side was the maternal tipuna Matoitoi, who is listed in the Blue Book (which contains the names of all Ngāi Tahu kaumātua alive in 1848 and 1849).

In his 20s, while rabbiting in rural Central Otago, Boko ended up in Dunedin hospital for treatment on a recurring leg injury. And in a classic romance story – he fell in love with his nurse.

Ruth Sim was the daughter of fourth generation Scottish immigrants and was from Tapanui, where her father owned a trucking business.

Boko and Ruth married and settled in Ōmarama, Boko working as a gardener and general-hand on a high country sheep station in the upper reaches of the Waitaki River.

“A year later, Dad got a more permanent job with the Ministry of Works. He was a grader driver for all of his working life that I remember. We lived in a Ministry of Works house, and went to the local Ōmarama primary school. Then, when it was time to go to High School, we all shifted as a family down to Maheno, a little village on the outskirts of Oamaru.”

By then, there were six children: Ross, Teri, Louise, Taura, Peter, and Pania.

At Waitaki Boys High School, Ross and his brother Teri excelled at art. Art teacher Colin Wheeler was an extraordinary technician in pencil drawing and poster colour painting, and that’s mainly the art they did at high school.

“Both my brother Teri and I were always complimented on our art ability, so it was only natural that we would go on to art school.”

Still Ross had no inkling of the way he would one day be able to bring his Ngāi Tahu whakapapa into his art.

In the North Island, the innovative educationalist Gordon Tovey had inspired a generation of young Māori artists to draw on their Māori heritage, and a new contemporary Māori art genre was growing. The likes of Ralph Hotere, Para Matchitt, Sandy Adsett, and Cliff Whiting were making names for themselves.

But back in Dunedin, young Ross Hemera had no idea that this “renaissance” was happening.

“I thought there were only two Māori artists. One of them was my brother Teri, the other myself,” he says.

“Because we were isolated in the South Island. We didn’t know a lot about what was happening in the north.”

Nor would he have considered that it was possible that his Ngāi Tahu heritage could ever have a place in his art practice.

It was not until he moved to Auckland to attend teachers’ training college that he had any notion of the movement that had developed over the previous decade.

Back in Dunedin, Ross and Teri had met and been nurtured by Malcolm and Elizabeth Murchie. Elizabeth went on to become a President of the Māori Women’s Welfare League. At the time Malcolm was a liberal studies lecturer at Otago Polytechnic. In a town where Māori students were still somewhat of a novelty, they took the Hemera brothers under their wing.

When Ross moved to Auckland, the kaitiaki role was taken up by Georgina Kirby, another well-respected female Māori leader.

“She was very much part of the art scene. At the time the New Zealand Māori Artists and Writers (later renamed Ngā Puna Waihanga) had their first hui in Te Kaha in 1972.

“Although I didn’t go to that first hui, it was through Georgina and Arnold Wilson that I met other Māori artists. I think I went to all subsequent hui bar one.”

To Ross, a whole new world had opened up. He quickly became aware that his Māori whakapapa and his work as an artist were not mutually exclusive.

“I found out that I wasn’t alone. There was amazing amount of stuff going on. There were artists and creative minds, writers – it was quite amazing.

“I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t gone North. All our art schools then were very Eurocentric. So the great artists of the world are the ones you wanted to emulate and you held them in high esteem. From Rubens to the Cubists and Picasso – all figures of that European western tradition. You were drawn in towards them.”

The giant mural by Para Matchitt that adorns the wharekai Kimiora at Tūrangawaewae was one work that stood out to him.

“I was just so impressed. First with the aesthetic that he was using, and secondly, the expanse of it. I thought it was amazing. It was something that identified Māori. I thought, ‘Man, this is about me. This is something I can really identify with.’ From then on, I started developing my own work and things progressed to what they are now.

“I was so excited by the scale of the mural I looked for opportunities to do similar things. I did a mural for the library in my first teaching job at Glenfield College. From that point you could categorically classify my work as contemporary Māori art.”

Ross had long thought about the need for art educators to move away from the Eurocentric approach to teaching, and in 1983 he got the chance to put some of ideas to work.

His former mentor Malcolm Murchie was now the principal of Waiariki Community College in Rotorua and he employed Ross to help establish an art programme.

“I wanted a focus on kaupapa Māori within design. When I arrived there, there was nothing and I so started taking a number of night and community education classes. Then they were able to secure funding to set up craft design programmes around the country – at Waiariki we called ours, ‘Craft Design Māori.’

“That was an amazing time. I felt that this was the purpose of my working life. This was a time that arts education was blossoming. There was enough pūtea. By the time I left in 1994 there was a full programme – a certificate and diploma in contemporary Māori design and really great Māori artists on the staff like Tina Wirihana, Lyonel Grant, and Bob Jahnke.

Some of the student graduates from that programme are high profile artists in their own right now, like June Grant, Simon Lardelli, Louise Purvis, Todd Couper, Wi Taepa, Kerry Thompson and Lewis Gardiner.

From Waiariki, Ross and his whānau moved to Wellington so he could take up a role at Wellington Polytechnic, which has since merged with Massey University.

Above: Kauati Lights, Queenstown.

In the past few years he has been Professor of Māori Art and Design, and the director of Māori development in the College of Creative Arts.

But while after 21 years he is retiring from the university, he will never retire as an artist. The “For Sale” sign outside the Whitby home he shares with his wife Julie indicates a new stage in his career. They’ll be moving to Tauranga where Ross’ first job will be to build a new studio, to carry on the creative art practice that he has successfully managed alongside his academic career.

Ross is primarily known for his mixed media sculptural work. He merges the artistic traditions of his tīpuna with European forms and material. His works are creative expressions of contemporary Māori pattern and design, referencing the ancient imagery of the Waitaha and Ngāti Māmoe within the context of taonga tuku iho. The expression of Ngāi Tahu cultural values and beliefs is the primary focus of his work, including such concepts as whakapapa, whenua, mana, taonga, and whānau.

“Any chance I get to go home and visit the tīpuna, I will go. They are the biggest influence on my art. When I think about them I go right back to when we were kids and the strong impression they made. How they are drawn, the shapes, the forms, and motifs that have been created is something that is quite unique and something that I find absolutely fascinating.”

The Eurocentric aesthetic that was drilled into him at art school guides his work, but the rock drawings of his childhood have become an intrinsic part of his practice.

“They’re imprinted on my mind and in my heart,” he explains.

“Their aesthetic is simply amazing. How they are drawn, the shapes, the forms, and motifs that have been created is something that is quite unique and something that I find absolutely fascinating. Any chance I get to go home and visit the tīpuna, I will go.

“They are the biggest influence on my art. When I think about them I go right back to when we were kids and the strong impression they made. From an artist’s point of view and a human point of view, there’s a strong connection I feel with them.”

The passion Ross feels for his Ngāi Tahu whakapapa has been put to good use.

He incorporated rock art images into the design for the first set of Aho brand shawls – a line of high-quality possum fur and merino wool shawls developed by Ngāi Tahu in conjunction with AgResearch.

He led the development of artwork in two Pou Whenua projects, embodying Ngāi Tahu Property’s policy of introducing Ngāi Tahu art into any new builds.

In the Post Office Precinct in Queenstown Ross created coloured glass windows, cut glass panels, and seven large light globes that interpret the narrative of the local tipuna, Hakitekura. He was responsible for the full-scale Tuhituhi Whenua mural on the new civic buildings in Christchurch.

Ross is also part of Paemanu, the Ngāi Tahu contemporary Māori artists’ trust alongside artists including Areta Wilkinson, Rachael Rakena, Simon Kaan, Jon Tootill, Neil Pardington, and Priscilla Cowie. It aims to cultivate a vibrant Ngāi Tahu visual culture for future generations by exploring Ngāi Tahutanga through contemporary visual art.

The trust’s name, Paemanu, is taken from one of Ross’ earlier works, exhibited in the Ngāi Tahu Mō Tātou exhibition at Te Papa.

“One of our most famous images is of the birdman. Two out-stretched wings with little birds perched on each, and that’s what I have been inspired by. That one image says so much about who and what we are.”

But as he builds his new workshop in Tauranga, Ross will be thinking about how he will undertake his vision for a new challenge – a project that looks to respond to the Ngāi Tahu aesthetic through art.

“Our writers are doing a good job in getting our history recorded in written form. I want to refer to our art and design, to our visual and material culture to tell our history and think about our future through making new art.”