Kā Whare Māori ki Awarua: Bluff’s “Māori Houses”

Mar 31, 2017

Nā Michael J. Stevens (nō te whānau Metzger)

Te Rau Aroha Marae. PHOTO: Tony Bridge.

Te Rau Aroha Marae is the focal point of Awarua Rūnaka and is at the heart of the Bluff community. The marae complex’s central feature is its distinctively-shaped wharenui, Tahu Pōtiki, which cuts a remarkable figure from land, sea, and air. It was opened in February 2003 after nearly four years of carving, weaving, and painting by a diverse team of mostly local volunteers led by Cliff and Heather Whiting, with substantial support from a team of Kāti Kurī from Kaikōura, led by Bill Solomon until his sudden death on the marae in February 2001. The wharenui was effectively clipped onto the west side of the wharekai, Te Rau Aroha, which was opened in 1985. The expanded facility, which opens out on to a large paved marae ātea, was the fulfilment of a 50-year dream. It was also the finishing touch to Bluff’s fourth communal Māori building since 1881 when the port’s first so-called “Māori House” was opened.

Bluff

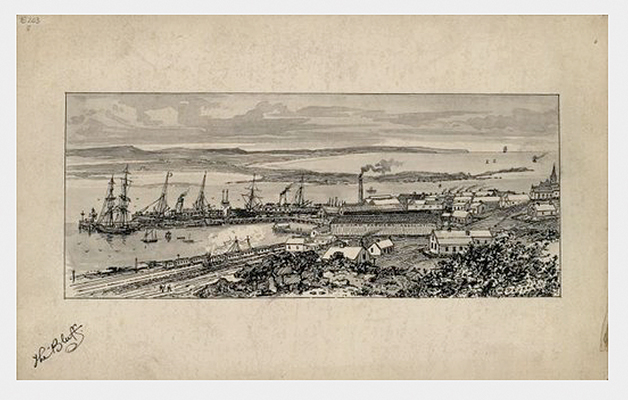

This sketch of Bluff from c.1900 shows the chimney that was part of the Southland Frozen Meat Company’s freezing works. The port’s first Māori House stood immediately west of this facility from 1881 until c.1903. IMAGE: Deverell, Walter, ca 1853-1920: The Bluff.

[ca 1900]. Ref: E-203-q-005. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Awarua, or Bluff Harbour, was a site of cross-cultural encounter from at least as early as 1813. A shore-whaling station was established in 1836 in what later became the township, and the port became a site of cross-cultural entanglement. Although Bluff was only one of several multi-ethnic coastal enclaves located on both sides of Foveaux Strait between the 1820s and 1860s, colonial settlement from the late-1850s reduced the relevance and viability of other sites, while Bluff’s strategic and economic importance grew. Increasing numbers of

Kāi Tahu began visiting and relocating to the budding port-town. Nearby Ruapuke Island, where Tuhawaiki and other Kāi Tahu rakatira signed a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi in June 1840, boasted a population of 200 in 1844. However, by 1887 this was down to a mere

16 people.

On 3 January 1881 the Southland Times reported at length on the “Opening of the Māori House at Bluff”, which produced “quite a large gathering of natives.” According to the newspaper, the government had built the house “for the purpose of accommodating the natives when they come across from Ruapuke and Stewart Island.”

The “Māori House”, 1881–c. 1903

Bluff’s foreshore freezing works ceased operating in the 1920s and was thereafter used as an oyster and fish processing facility until its demolition in 2016. Ironically, its last tenant was Ngāi Tahu Seafood. The company truck parked on the grass berm is where the Māori House was located.” PHOTO: Michael Stevens.

A letter written by Isaac Newton Watt from Southland’s Native Office in 1866 to the Undersecretary of the Native Department, illustrates Bluff’s growing significance in southern Kāi Tahu life from the mid-to-late 19th century. Watt explained that Kāi Tahu people from throughout Foveaux Strait regularly visited Bluff to sell produce and therefore required a Māori Boarding House, more commonly known as a “Native Hostelry”. Such a building, Watt insisted, would prevent these people from staying in the port’s pubs where they could experience “injury to their sobriety and morals.”

On 3 January 1881 the Southland Times reported at length on the “Opening of the Māori House at Bluff”, which produced “quite a large gathering of natives.” According to the newspaper, the government had built the house “for the purpose of accommodating the natives when they come across from Ruapuke and Stewart Island.”

With the notable exception of Christchurch, Native hostelries were established in colonial settlements throughout New Zealand between the 1840s and the 1860s. These were usually provided by central government, albeit after prodding from missionaries and Māori leaders, and often in spite of considerable opposition from Pākehā. For instance, the politician William Fox told Parliament in 1856 that a proposed Māori hostelry for Wellington would “engender immorality, filth, and pestilence”, while one of his colleagues predicted a cheapening of adjacent property values and what is now referred to as “white-flight.”

Nothing seems to have come from Watt’s proposal, but 14 years later, in June 1880, the Southland Times reported that a meeting of the Bluff Harbour Board had agreed to the government’s request for a “Māori house” to be sited “on the Bluff Foreshore”. In a world without resource consents and building inspectors, things moved quickly. On 3 January 1881 the Southland Times reported at length on the “Opening of the Māori House at Bluff”, which produced “quite a large gathering of natives.”

According to the newspaper, the government had built the house “for the purpose of accommodating the natives when they come across from Ruapuke and Stewart Island.” The opening was presided over by the noted Ruapuke-based kaumātua, Teone Topi Patuki, who timed it to coincide with Bluff’s New Year’s Day regatta that drew many visitors to the port. Ironically, given Watt’s concerns, the nearly 70 Māori in attendance enjoyed a “large spread” at the nearby Provincial Hotel before adjourning to the Athenaeum Hall (now Bluff’s Te Ara o Kiwa Sea Scout Hall), where they “danced the old year out and new year in.” The Rev. C. S. Ross was passing through Bluff at the time and noted that “tribes as far remote as the Waitaki” attended the “house-warming”. “On our arrival at the Bluff,” he wrote, “the feast had been in progress for three days & Māoris swarmed over the beach in hilarious mood.”

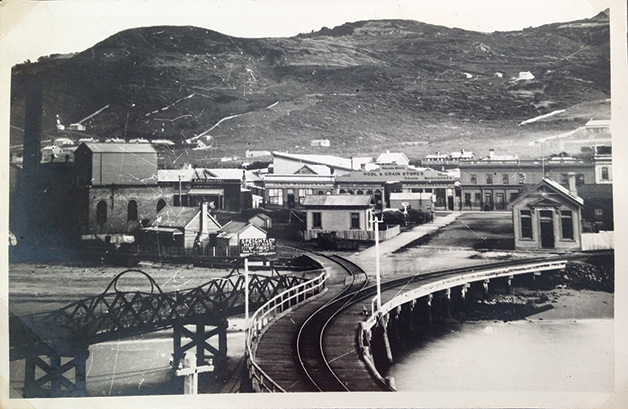

The Māori House is clearly visible in this photo from c.1900 that looks back towards Bluff from the Town Wharf. The port’s Custom House and Countess of Glasgow Sailors’ Rest can also be seen and the Golden Age Hotel is in the background. PHOTO: Rata Harland Collection, courtesy of Maurice Skerrett.

Kāi Tahu groups would have made use of the Māori House during seasonal trips to and from the Tītī Islands, as well as journeys to and from Ruapuke and Rakiura throughout the year. There is evidence that Topi’s brother, the noted seaman and whaler Tohi Te Marama (commonly known as “Buller”) and his wife, Pani (also known as Mary Ann Harding) were its resident caretakers for some time. The Māori House was also used to host manuhiri including, in June 1882, the Taranaki pacifist leaders Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi, of Parihaka fame, during their 11-month term of “honourable restraint” in the South Island. The guests were treated to tītī and tio, but also a whaikōrero in which, according to their warder and interpreter, John P. Ward, Topi dismissed their prophetic status and told them to cultivate their ample lands and embrace capitalism. When Topi died in 1900 aged about 90, Kāi Tahu delegations from “Stewart Island, Riverton, Colac Bay, Otago Heads, Romahapa, and from as far up as Lake Ellesmere and Little River” gathered with “the Bluff natives” at the Māori House before and after travelling to Ruapuke for his tangihanga. However, unlike Topi, the Māori House did not make old bones. Like Parihaka, it was in the way.

New Zealand’s frozen meat trade with Britain in the 1880s led to the development of a freezing works on the Bluff foreshore, immediately east of the Māori House. The Māori House’s days were numbered. Physical access seems to have been restricted by at least the early 1890s, prompting Southern Māori MHR, Ruapuke-born Tame Parata, to appeal to the Minister of Native Affairs, Sir James Carroll, for relief. Although Carroll assured Parata that free access by sea or wharf would continue, the hostel was torn down within a decade. A similar thing happened in Dunedin where a Native Hostel built on Princes Street in 1860 was demolished a year later: a victim of gold rush-fuelled expansion. However, while the Dunedin hostel was not replaced, the Bluff one was.

The first gathering held in “the new Native House”, as reported in the Southland Times, was a meeting in June 1903 of the Araiteuru Māori Council, one of 19 councils established under the Māori Councils Act 1900 that [Minister of Native Affairs, Sir James] Carroll shepherded through Parliament.

Tarere ki Whenua Uta, c.1903-present-day

This sketch of Tarere ki Whenua Uta, Bluff’s second Māori House, was produced in the 1980s prior to renovations later that decade. IMAGE: courtesy of Te Rūnaka o Awarua.

According to W. A. Taylor, the government agreed to subsidise the second “Bluff Māori Hostel” in August 1902. Although port officials still referred to the Māori House on the foreshore as late as May 1903, its replacement was built that year on a section in Bradshaw Street at an overall cost to the government of £500 – twice what it had budgeted. This five-roomed building was named Tarere ki Whenua Uta, an old name for a stretch of nearby coastline. It functioned much the same as the foreshore hostel had, although, because Bluff was by then home to a relatively stable Kāi Tahu population, it was increasingly used as a community hall and political meeting place.

Indeed, the first gathering held in “the new Native House”, as reported in the Southland Times, was a meeting in June 1903 of the Araiteuru Māori Council, one of 19 councils established under the Māori Councils Act 1900 that Carroll shepherded through Parliament. The meeting was presided over by Tiemi Hipi (James Apes) from Waikouaiti (i.e. Karitāne), with further delegates in attendance from Moeraki, Port Molyneux (Kaka Point), Riverton, Colac Bay, and Rakiura. One of the main items of business related to the Kīngitanga and resulted in an address to parliament “on behalf of the Māoris of Southland … objecting to the gazetting of Mahuta as ‘King’”, a cause that Parata proceeded to devote considerable parliamentary time to. It also established a “Premises Committee” for Tarere ki Whenua Uta after Parata explained that control and upkeep of the new building would be the responsibility of Bluff-based Māori.

This local control outlasted the relatively short-lived Māori Councils experiment. It also occurred in spite of the fact that the building and the two residential sections of land associated with it were Crown-owned until the mid-20th century. The mixed-management arrangement this spawned was evident in the late 1920s when some Kāi Tahu individuals took up residence in the hostel without permission, or at least ongoing support, of other local Kāi Tahu: a group led by George Skerrett successfully lobbied the Department of Native Affairs to evict these people and issue trespass notices against them. However, it seems that things returned to business as usual. In 1939, Norman Bradshaw explained to the Undersecretary for Lands that the hostel was “still used for the purpose for which it was built, especially when the Natives are getting ready to embark for the Tītī Islands.” It was at this time that Bradshaw asked to purchase the unoccupied half of the reserve on which Tarere ki Whenua Uta stood, to build a family home on. Although permission was declined, he and his family played key roles in the management and expansion of Tarere ki Whenua Uta and successor buildings.

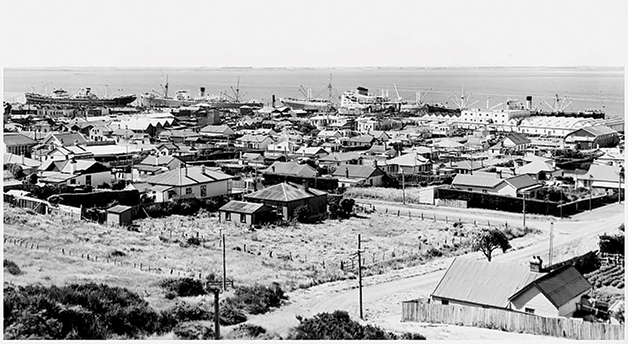

Tarere ki Whenua Uta sits at the centre of this photo that was probably taken in the 1940s. The land beside and behind the building are now part of the Te Rau Aroha Marae complex that was developed from the early 1980s.

PHOTO: supplied.

It was noted in 1950 that 450 people of Māori descent lived in Bluff (out of an overall population of about 2200), and while the hostel was used as a community centre, it required significant enlargement and modernising. Essential maintenance had been carried out, but an “active committee”, under the direction of Thomas Spencer JP, offered to raise funds to improve the building if its title was vested in local Māori. The Department of Māori Affairs and the Māori Land Court agreed to this proposal and transferred ownership to nine trustees of the beneficial owners – defined as “the Māoris resident at the Bluff, Stewart Island, and Ruapuke Island.” A 1948 suggestion that the hostel be sold to raise money for a meeting-house or hall, which the Southern Māori MP Eruera Tirikatene described as “urgently required”, was dropped when the business case did not stack up. However, the case was reignited in 1956 when the Māori Purposes Fund Board approved a grant of £500. This helped the Awarua Tribal Committee, led by Bob Whaitiri, to purchase another building in the early 1960s.

Over the next 20 years Tarere ki Whenua Uta was used to provide short-term accommodation to local families, often in times of financial hardship. Then in the late 1980s the building was re-piled, re-clad, and re-roofed, and had a front veranda added. It was thereafter used for tāngi, rūnaka meetings, and administration purposes until the early 2000s, and more recently as an after-school study centre. Although Tarere ki Whenua Uta is now at the end of its functional life, Bluff’s second Māori House has played an important role in the lives of Kāi Tahu throughout and beyond Murihiku for over five generations.

This story will be continued in the next issue.

Bluff-raised Dr Michael Stevens (nō Kāi Tahu) is a Senior Lecturer in Māori History based in the Department of History and Art History at the University of Otago. In 2013, with support from Awarua Rūnaka, he was awarded a highly competitive three-year Marsden Fast-Start research grant by the Royal Society of New Zealand to research and write a history of Bluff. This article draws on work from that project, the main output of which is a book, Between Local and Global: A World History of Bluff, to be published by Bridget Williams Books in 2018.