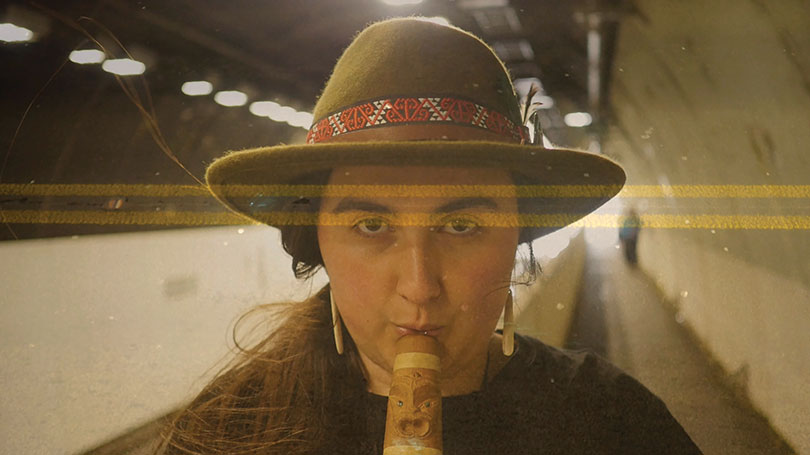

A human compass: Ruby Mae Hinepunui Solly on finding her way

Jun 29, 2021

Kāi Tahu are multi-faceted; this we know. But Ruby Mae Hinepunui Solly (Kāi Tahu – Waihao, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha,) takes multi-faceted to the next level. At just 25, Ruby has had more success than she’s willing to admit. Kaituhi Rachel Trow (Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Tūwharetoa) spoke to Ruby about her Kāi Tahutaka and the next generation of Māori storytellers.

With an impressive array of creative tools in her kete, Ruby is adamant she is Kāi Tahu before anything else. Poet, writer, cellist, taoka puoro practitioner, doctoral candidate, artist, music therapist: every part of Ruby is informed by her Kāi Tahutaka.

“Hearing people think of me as a Kāi Tahu writer before they think of me as any other kind of writer, I think that’s really beautiful,” she says. “It also gives you a scope, as in, I’m writing Kāi Tahu writing. I’m not writing poetry, I’m not writing fiction, I’m not writing non-fiction, I’m writing Kāi Tahu writing.”

Ruby is flattered to be thought of in this way – as a young wahine Māori she looked up to Hinemoana Baker as a writer who was Kāi Tahu first. Ruby is always quick to acknowledge the mana wāhine that came before her – from literary ancestors to her own tūpuna.

Life for young Ruby was based in the Central Plateau. Whakapapa Village, Raurimu, Rotorua and Taupō-nui-a-Tia were her schools, playgrounds, and resting places. She grew up away from her marae

at Waihao, but recalls it fondly. This bittersweet emotion is a theme in Ruby’s poetry collection, Tōku Pāpā, published earlier this year.

Her book’s namesake, her Kāi Tahu father, feeds many important memories from her childhood.

It is woven with heartwarming experiences with her Dad, many involving native manu, although no experience was quite as memorable as the time her Dad befriended a ruru and brought it home as a pet.

Ruru are a recurring theme in Ruby’s book, and life. She wears a pounamu ruru hei tiki around her neck. It looks heavy, handmade, powerful. The pounamu wasn’t crafted for her, but made for her.

She notes the Kāi Tahu kupu for ruru, ‘koukou’, was also the name of a tupuna wahine. It bears moko kauae, similar to a design she’s been mulling over for herself for some time. Carvings in the piece relate to the story of Māui and her namesake tupuna, Hinepunui.

Whakapapa is a consideration in all of Ruby’s work, whether it’s telling the stories of our ancestors or honouring her storytelling forebears. Photographs: Sebastian Lowe

The pounamu is perfect for Ruby, and the children she works with as a music therapist.

“It’s a really special kaitiaki when I’m working as a music therapist … kids are always holding it or playing with it,” she says. It’s easy to forget that, with all these other artistic pursuits Ruby follows, she’s also pursuing a PhD in health. This is where taoka puoro and the cello weave into Ruby’s story.

Ruby is whakamā about admitting she “really enjoyed lockdown”, partly because she managed to finish a taoka puoro album after reclaiming the art she was first taught as a child. Her “main instrument in te ao Pākehā” was the cello. On the album, she layers the two as a way of decolonising her own music practice. The album, titled Pōneke (a reo Māori name for Wellington) is also Ruby’s tribute to the Kāti Māmoe and Kāi Tahu movement southward from Wellington hundreds of years ago – a history that is sometimes forgotten.

Whakapapa is a consideration in all of Ruby’s work, whether it’s telling the stories of our ancestors or honouring her storytelling forebears. When Ruby talks about this new generation of storytellers she is part of, she’s sure to mention those who have come before, like Patricia Grace and Witi Ihimaera. “There’s not just a whakapapa within your whānau, there’s a whakapapa within the things you do.

“That’s a reason to keep you writing. They’ve put so much work in to enable us to have this platform where people are interested in what we have to say … you have to keep writing for Uncle Witi and Aunty Pat.”

And write she has. With one collection published before the age of 25, and another simmering away in the background, Ruby and her peers are living up to their ancestors’ wildest dreams. The popularity of other young indigenous writers, like essa may ranapiri and Tayi Tibble, shows these stories are more sought after than ever – but it’s because people like Patricia and Witi brought them to the table.

Being visible in her mahi and her Kāi Tahutaka is “really special, it’s like being a human compass.” By virtue of her work and who she is, she’s been able to connect people from around the motu who are lost, or want to know more about where they come from.

Connecting the dots for people, for whenua and whakapapa, fits well with the next project on Ruby’s horizon. She’s researching star kōrero – from a uniquely Kāi Tahu perspective, of course. She keeps the gist under wraps but says she hopes to “create something that people are going to be able to use to connect into who they are.

As long as I’m helping people connect into who they are, that’s what success looks like.”

There are lots of bright, shiny things in Ruby’s future. Some things are clear, like her plans for moko kauae. Some things aren’t so clear, like when audiences will be lucky enough to read her next poetry book.