A Legacy of Kaitiakitaka

Feb 12, 2025

Nā Nikki-Leigh Condon

Nā Nikki-Leigh Condon

HELEN RASMUSSEN (KĀI TAHU – KĀTI MAHAKI, KĀTI IRAKEHU; KĀTI MĀMOE) fondly recalls her unique upbringing in “one of the harshest places to raise a family.”

Growing up in Mahitahi, Bruce Bay, in a remote part of Tai Poutini, her childhood was rooted in tradition and guided by values passed down through generations.

Seventy kilometres from the nearest town, her childhood became a story of adaptation, connection to the land, and resilience ... “I grew up in one of the most isolated parts of New Zealand.”

This isolation instilled in Helen a sense of fortitude, resourcefulness and profound respect for the whenua. These qualities would eventually lead to her receiving the Order of Merit for her services to Māori and conservation – a recognition she humbly attributes to the efforts of her whānau, community, and tīpuna who set her on this path.

“Our only connection to the outside world was a gravel road built by my great-grandmother and the young women of our whānau.”

The women took on the challenge of constructing this vital lifeline while the men were at work, connecting their kāika to the nearest township. It was an early testament to the strength of the wāhine in her whānau – a strength that has echoed throughout her life.

The family home, built by her father from two salvaged sawmill houses, became a lasting symbol of whānau unity and determination.

“Every weekend, we would straighten the nails for reuse.”

She and her siblings travelled 40 kilometres every weekend to help, a lesson in patience and persistence that formed the foundation of her strong work ethic. Her whānau lived a simple lifestyle, relying on mahika kai practices and planting bush gardens.

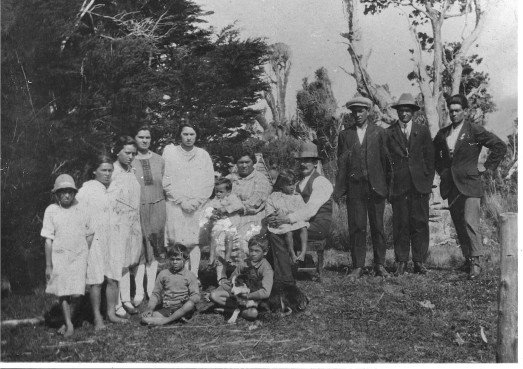

Helen’s father Bob Wilson with his parents and siblings at Hunts Beach circa 1930.

“We knew the soil was richer where ribbonwood trees grew,” she says, describing how they cut these trees to prepare gardens on a three-year rotation.

These gardens were essential for growing rīwai, carrots and parsnips. Without refrigeration, food was preserved in uphill sand dune tunnels where vegetables were stored for winter.

Her father, raised in the “old” ways, shared this inherited knowledge with Helen and her siblings. “Dad taught us how to divine for water and the time-honoured ways of catching tuna and whitebait.”

The whānau also wove kete to transport kai, including shellfish, back to their whare. In the early days of whitebaiting, before refrigeration, the family kept the catch in live nets in the backwater, ensuring the fish stayed fresh for weekly sales when the fridge truck arrived … “We sold whitebait by the box.”

Helen's grandparents with four of their children processing gold from black sand on the beach at Hunts Beach circa 1930.

Despite the hardships, Helen reflects on her childhood with warmth.

“Our parents raised us in what was arguably one of the most challenging environments, but what stands out is the closeness of our whānau – the whanaungataka of our aunties, uncles and cousins.”

Music, waiata and dancing were woven into their lives, and the family always found ways to have fun together, even in the most trying times.

“We lived without power,” she says.

“Mum would wheel the washing down to the river to rinse our clothes and bring them back to hang. We had only two sets of clothes – one for school and one for play – and neither was allowed to get dirty.

Life was simple, and she reflects that by today’s standards they lived below the poverty line, “but we were totally unaware, as that was how our tīpuna and whānau had always lived.”

Helen carried this connection to the land and sustainable living into adulthood, applying the lessons of resourcefulness, respect for nature, and community."

Becoming New Zealand’s first female Māori skipper, she led her own crew in commercial crayfishing and continued her family’s practices of kaitiakitaka. For Helen, living off the land and sea was more than survival – it was an honouring of whakapapa and a way of life.

It was during a Waitangi hui on the settlement with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu that Helen felt the pull to represent her people.

“I went to a meeting, and there was a group claiming to represent the Māori of South Westland, our area,” she recalls. “That’s when I knew something had to be done.”

She joined forces with her cousin, Paul Madgwick, to begin the kōrero that would lead to Te Rūnanga o Makaawhio.

“The first step was to form a steering committee. So, we put a pānui in the paper, inviting anyone with whakapapa to our area and our common ancestor to come to a hui.”

The first hui, held on August 28, 1988 at Bruce Bay Hall, gathered more than 250 people despite the hall having sat unused for 20 years.

“The hall was filled with sphagnum moss, and we had to clear it out and build toilets before we could even hold the meeting.”

The turnout was overwhelming, with whānau arriving from across NZ and even Australia. Inside, whakapapa charts lined the walls, meticulously written out by Paul so everyone could trace their connections. “Seeing people finding their place in the whakapapa, realising how we were all related – it was truly amazing.”

That day, the first rūnaka was elected with 30 members, and Te Rūnanga o Makaawhio was officially incorporated. Helen’s father, Bob Wilson, was chosen as the first upoko, continuing the family’s legacy of representing their people.

“We finally had our whānau voice in the political and social spheres,”

Helen says, reflecting on the significance of that moment. Years later, Helen’s father led a hīkoi to visit their common ancestor, Te Koeti Tūranga, at his final resting place.

As they cleared moss from his headstone, they discovered they had formed the rūnaka on the 97th anniversary of Te Koeti Tūranga’s death – a powerful coincidence that strengthened their connection to their tīpuna.

“It was a deeply emotional moment for us all. We realised we were standing on the shoulders of our ancestors, continuing the work they began.”

One of Helen’s most significant achievements with the rūnaka was building a partnership with the Department of Conservation (DOC), recognising that 95 per cent of South Westland was under DOC management.

She knew collaboration was essential to ensuring Māori values were part of conservation efforts. Under her leadership, the rūnaka formed sub-committees like the Kaitiaki Rōpū, which worked on policy development and local conservation projects. These initiatives brought traditional Māori knowledge into modern conservation practices, ensuring kaitiakitaka remained central to land management.

Helen’s role in bridging Māori values with DOC policies has had a lasting impact, shaping how South Westland’s resources are managed today. Her work on the Conservation Board further strengthened this partnership, marking her a leader in conservation and the protection of cultural heritage.

Helen with Governor General Cindy Kiro at Helen’s Investiture Ceremony.

Reflecting on her Order of Merit, Helen remains humble. “I was deeply honoured, and I accepted it not just for myself, but for all those who worked tirelessly alongside me – our community, dedicated to conservation, sustainability, and tino rangatiratanga.”

To Helen, the honour symbolises the efforts of her whānau and tīpuna. “When I wear the medal, I wear it with pride, knowing it represents the collective legacy of those who came before me.”

A whakataukī close to her heart reminds her of this enduring legacy: “We stand on the shoulders of giants.”

For Helen, each generation weaves its own threads into the korowai of life. Her hope is simple yet profound: “I want my mokopuna to thrive on our whenua, stand proud in our takiwā, and grow up with the laughter, waiata, and memories that shaped my life.”

Often, she reflects, the path forward is best understood by looking back: “If you don’t know where you come from, you’ll never know where to go.”