Cultural Connection

Jul 3, 2017

Nic Low is part of a growing Melbourne-based taurahere group united in their desire to reconnect with their language and culture from a distance. This rōpū are among the 50 per cent of Kāi Tahu living outside the takiwā.

Ngāi Tahu whanui gather in Melbourne for the first weekend wānaka reo.

A voice sings out: Areare-mai-rā-ōu-tarika!

Thirty-four voices sing back, in a chorus of different accents. Some are Aussie, some Kiwi, most of them somewhere in between. Some ring proud and confident; others cradle the unfamiliar Māori syllables like a new parent cradling their first child.

Areare-mai-rā-ōu-tarika!

Lend me your ears!

Quiet falls. Through the open classroom window comes the pulse of big-city traffic, the rumble and clang of a tram. We’re in Melbourne, in a community centre that was once a school. These walls have overheard conversation in English, Greek, Italian, Turkish, and Lebanese, and local indigenous language Wurundjeri. Now, for the first time, they’re hearing Māori. The Kāi Tahu in Victoria taurahere, six months after its birth, has organised its first weekend wānaka reo. This is also the first time the tribe’s language revitalisation team, Kotahi Mano Kāika, has left the Kāi Tahu takiwā to teach.

Kō Aoraki tōhoku mauka

Kō Waitaki tōhoku awa…

Kaiako Victoria Campbell kicks things off with mihimihi. She explains how this most basic form of greeting is rooted in connection to the land. She talks about papatūwhenua and tūrangawaewae: the place where your ancestors lie stacked, the harbour for your feet.

“Name your mountain, your river, and your coast, and that’s how people know who you are,” she says.

Looking round the room, there’s hesitation mixed with the excitement. Which mountain? Which river? For the young ones born here, those who haven’t been home in decades, for the global nomads with no home, or those who shuttle back and forth all the time – what do they say to Nō hea koe?

Tori smiles. “The easiest thing to say is ‘Nō Kāi Tahu ahau.’”

Kaiako and Kotahi Mano Kāika head Victoria Campbell.

It’s the easiest, but it’s far from simple. Spiritually and politically, so much of Kāi Tahu culture and identity is based on ancestral land and the home fires, ahi kā. Yet we’re fast becoming a globalised people: of the tribe’s 57,000 registered members, 50% of us live outside the takiwā, which is huge for a culture so rooted in place. Most are in the North Island, but 6013 live overseas. There are 5185 in Australia: a whopping 9%.

So what does it mean to be Kāi Tahu on Aboriginal land? Why is the new Victorian taurahere group learning te reo Māori and reaching back to the iwi? Why is the iwi reaching out to those living overseas?

“When I found out there were so many registered members here, I asked myself how I could strengthen my own Ngāitahutanga, and help others grow more confident about using te reo and tikanga in their everyday lives.”

Haileigh Russell-Wright Ōtākou

When Danella Webb (Ngāti Waewae) got out of bed on Sunday, she had no idea that by the end of the day she’d be helping to spearhead a new taurahere group in Melbourne. She had the day off from her job as a senior manager at the Austin Hospital, and all she knew was that the Ngāi Tahu roadshow was coming to town.

“I was just excited. Nothing was going to stop me being there. I didn’t have to clear my calendar, because that’s how boring I am; but if I’d had a full calendar, I would have cancelled everything!”

At the roadshow she and her sisters Nicola and Lara found themselves talking to Michael Crofts Snr (Te Ngāi Tūāhuriri), Haileigh Russell-Wright (Ōtākou), and myself (Ōraka-Aparima). Te Rūnanga staff had pointed out that there were more than 600 “Tahus” in Melbourne, but no taurahere group.

“I have my immediate family here,” Danella says, “but I was looking for a wider connection to Ngāi Tahu. We all wanted to connect and learn and create a supportive environment for our whanauka, and we knew that if we were looking for that, others would be as well.”

Melbourne whānau get to grips with te reo basics

Haileigh Russell-Wright has strong connections to Ōtākou. Where Danella and her whānau were seeking to learn more, Haileigh was looking to keep her knowledge alive, and pass it on.

“When I found out there were so many registered members here, I asked myself how I could strengthen my own Ngāitahutanga, and help others grow more confident about using te reo and tikanga in their everyday lives.”

Fast-forward through months of planning in cafes and each other’s homes, and the group was born. Between 30 and 40 people began meeting regularly for whānau lunches at a thriving local environment centre. They affiliated to Ōraka-Aparima, Wairewa, Ōtākou, Rāpaki, Tuahiwi, Arowhenua, Awarua, Waihōpai, Moeraki, Arahura, Hokonui, and Waihao; those who didn’t know their links came along to find out. Each time people stood to mihi, several would share emotional stories about how they or their elders were denied the chance to speak or learn Māori. The message came through loud and clear: we want that chance to learn, and for our kids, too.

While some grumbled that they were too old to start now, or wondered where they could use te reo in Melbourne, all agreed the language was more than words.

“It’s also culture and history,” Haileigh says. She’d studied Māori at school and was keen to speak more with her whānau. “When you learn te reo, you’re learning values, and when you teach it, you’re teaching the world-view as well.”

With the support of the Ngāi Tahu Fund and Kotahi Mano Kāika, on the 8th of April we gathered to begin.

Areare-mai-rā-ōu-tarika!

After a lunch break spent primarily trying to work out who’s related to whom, the whānau return their attention to Tori at the front of the classroom. It’s time for waiata practice. The group is learning “Ka tū te tītī” to tautoko our speaker at the next Ngāi Tahu roadshow. It’s the perfect choice for a taurahere, about the far-flying migrations of the tītī, and standing strong in a new world. In between games and grammar lessons and coffee, we also talk star lore and the constellations used for navigation, and the different waves of waka migration to Aotearoa.

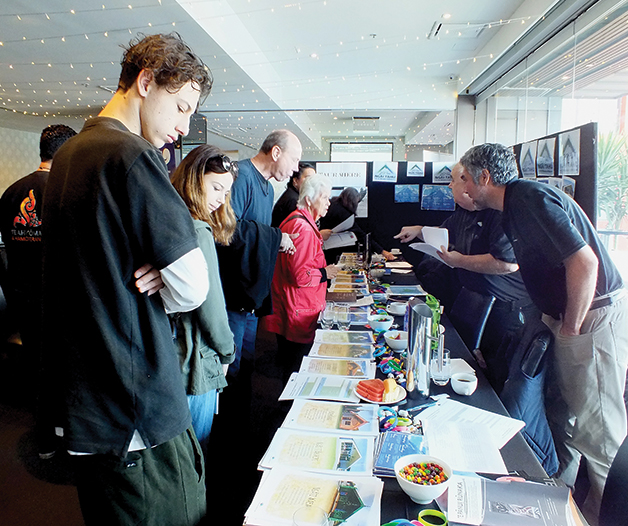

New members join at the taurahere table at the 2017 Melbourne Roadshow stand, run with the help of Taurahere Advisor Anthony Tipene-Matua.

From this knowledge, another strand of Kāi Tahu tradition emerges: we come from a long line of explorers, travellers, and migrants who carried their culture overseas. As takata whenua we emphasise connection to ancestral land. But we also have a rich history of making new homes. The Kāi Tahu story begins in Hawaiki in East Polynesia, and follows waves of migration into Te Ika a Māui, then Te Waipounamu; only it doesn’t end there. There’s another land we reached, and later settled: Ahitereiria.

Few people know it, but Māori was actually spoken in Australia long before English. At a site in northern New South Wales, archaeologists have found obsidian from Tūhua (Mayor Island in the Bay of Plenty) and an adze of Norfolk Island basalt in an East Polynesian style. “It’s the same age as the settlement of New Zealand,” archaeologist Atholl Anderson said in a recent interview. Those voyagers had Polynesian roots, had been to New Zealand, travelled to the Kermadecs then west to Norfolk Island, and then on to New South Wales. It means Māori reached Australia at least 400 years before Captain Cook. Who knows what conversations took place with Aboriginal people back when their languages were as strong as ours?

From the 1820s, Australian ships regularly called at Murihiku, and southern chiefs returned to Australia to trade in flax and guns. The Kāi Tahu dialect was heard in Sydney’s auction rooms in 1838 when Tūhawaiki, Karetai, Taiaroa, Topi Patuki, and Haereroa went to sell land. In the 20th century, waves of Kāi Tahu went west for work in shearing, labouring, fishing and pāua diving. During the mining boom, many of us had whānau down the mines or out on the rigs. The cities lured us into urban jobs. For some, those visits had no bearing on the compass of home. But many settled, intermarried, had kids, stayed.

Kaumātua Michael Crofts Snr welcomes everyone to the third wānaka reo.

Melbourne kaumātua Michael Crofts Snr, who guides and supports the taurahere, hails from Tūāhuriri, and came to Australia in 1980. In New Zealand he’d done butchery work, shucked oysters, and skinned deer, but his strong suit was filleting fish. Word of his prowess reached the owner of a fish stall in Melbourne’s Footscray Market. “I’d worked at Ferrin’s Fish Market in Christchurch,” Michael said. “The place was full of Hungarians, Bulgarians, Poms, and I could beat them all. So I joked to this guy I was the best filleter in the world – and he took me on my word!” Michael and his wife Joan only intended to stay a couple of years. It’s been 37 so far.

Since reconnecting with their Māoritanga through the group, several members have already decided to return to New Zealand. Some, like me, live here but can’t stay away from family and whenua in Te Waipounamu for more than a few months. Some, like Danella, say their sense of being Māori doesn’t depend on standing on Kāi Tahu soil, though that may change. And some are in Australia for good. Michael and Joan’s beautiful house is filled with carvings and photos of te ao Māori, but Melbourne is now home.

“It was important for us to connect with the Melbourne group because through this initiative they’ve shown their passion for our language and culture. It was also an opportunity to make sure te reo Kāi Tahu is heard throughout the world, no matter where our whānau choose to reside.”

Tori Campbell Kotahi Mano Kāika

Areare-mai-rā-ōu-tarika!

Beginners practice simple sentences: Kō Jon ahau. Kō Moira koe. Everyone stands in a big circle to mime and memorise every family relationship under the sun. Irāmutu, pēpi, tungāne. Ko Sarah tōku tamāhine. Kō Josh tōku tama.

With te reo Māori, it’s all about the next generations. Knowing that so many Kāi Tahu families may never return, Kotahi Mano Kāika (KMK) decided it was important to trial teaching overseas.

“Kia tautoko i kā whānau e kākau nui ana ki tō tātou nei reo me ōhona tikaka,” KMK head Tori Campbell says. “Kia rere te reo Kāi Tahu ki kā tōpito katoa o te ao whānui.

“It was important for us to connect with the Melbourne group because through this initiative they’ve shown their passion for our language and culture. It was also an opportunity to make sure te reo Kāi Tahu is heard throughout the world, no matter where our whānau choose to reside.”

Waiata practise.

The tribe is increasingly reaching out to those around the world, with roadshows now going as far afield as London. Speaking in Melbourne, interim Kaiwhakahaere Lisa Tumahai emphasised the importance of “being able to bring a bit of home to our whānau living here in Australia.”

“We’ve got 57,000 tribal members, 23,000 living in the tribal takiwā, but how do you connect to the rest of them? That’s why these roadshows are special. They’re quite an investment from the iwi, but the outcome is worth it.”

The Melbourne taurahere agrees. The group has since held two more wānaka reo with Darren Solomon and Karuna Thurlow as kaiako, and stood proud to welcome Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu for their return in 2017. Another round of pūtea from the Ngāi Tahu Fund means further wānaka on whakapapa, mahi toi and te reo are in the works. There are challenges – Melbourne is huge, everyone’s busy, it’s not easy keeping te reo front and centre in a foreign culture, and groups can fizzle once key organisers move on – which is why people are starting to think long-term.

Three energetic new members, Mina Te Huna (Rāpaki), Chloe Mommers (Ōtākou), and Jon Mommers (Ōtākou) have joined the committee to share the workload, and organising has gone from back-of-napkin sketches to online databases, and apps on our phones. Among the banter, phrases like “strategic planning” are starting to creep in. It’s good to dream, and the taurahere hopes that in another 25 years’ time, Melbourne will be a strong outpost of Ngāi Tahu culture. The vision is that tribal members wanting to see the world might choose Melbourne, because they’d get big-city hustle, yet could still learn te reo, live near whānau, debate history and whakapapa, perform kapa haka, or work for the tribe. Perhaps we’ll see such strongholds all over the world as Kāi Tahu expands.

Tayeisha Mommers and kaiako Karuna Thurlow at the third wānaka reo.

Statistics from 2011 show that almost one fifth of Māori now reside outside New Zealand. Demographer Dr Tahu Kukutai argues that this is unprecedented, and needs new thinking. But Māori overseas already have an ancient tradition for thinking about their former home.

Hawaiki is the legendary island our earliest ancestors set sail from. It’s the origin of whakapapa, language, and taonga like kūmara, and the spiritual homeland people return to at death.

There’s long been debate about where in Eastern Polynesia the physical island of Hawaiki lay. But many now argue that Hawaiki was not a single place, but an ancient name and concept applied to whatever homeland we’d left behind. Coming east across the Pacific, there are numerous islands with names like Savai’i, Ha’apai, Havai’i, and Hawai’i. It’s a point of origin that moves as we move, always one step back to the west.

And so for whānau in Australia, the relationship to New Zealand is clear: it’s our Hawaiki. It’s the origin of our stories, traditions, and language, and, in the age of air travel, the homeland that spirit and body may return to at death: Hawaiki-nui, Hawaiki-roa, Hawaiki-pāmamao, Hawaiki-Aotearoa.