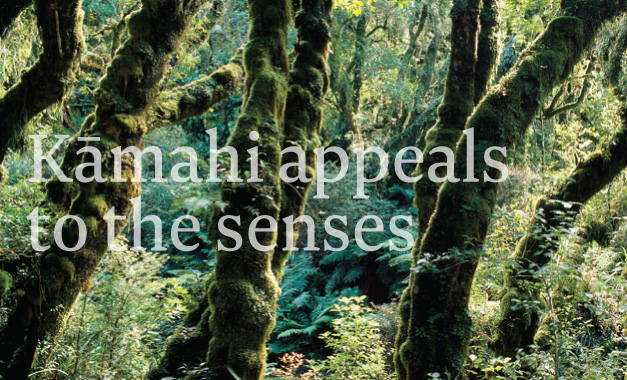

He Aitaka a TāneKamahi appeals to the senses

Apr 6, 2013

Like many tall canopy trees of our native forests, it is not until kāmahi explodes into full flower in late spring, summer and autumn that it really stands out against the earthy tones of the bush.

Its profusion of white flower spikes broadcasts the fact that this is the most abundant forest tree in Aotearoa, its range extending from sea level up to 900 metres of altitude from about the middle of Te Ika a Māui (the North Island) to Rakiura (Stewart Island).

This medium-sized spreading tree grows up to 25 metres tall and is usually found in the company of other broad-leaved species, particularly southern beeches, Southern rātā, and podocarps.

It often starts life as an epiphyte growing on tree ferns, and is regarded as a colonising species after forest fires. Experts say it is always prominent in second growth forests after they have been clear-felled.

Kāmahi is a dominant part of the forest canopy on Te Tai Poutini (West Coast), Rakiura and in the Catlins, on the south-east corner of Te Waipounamu.

In pre-European times, the tree was so valuable to Māori it was protected by tapu. When workers were clearing ground for cultivation, legend has it they were careful not to cut down all the tree’s limbs, or they or their spouse may suffer unfortunate consequences.

And yet there are very few references to the use of kāmahi by Māori in written records, which is surprising considering the range of specific uses found for other similar trees of the forest canopy.

Its most obvious value to Māori was as a dye. A pigment was extracted from kāmahi bark to dye cloaks and mats made of harakeke, kiekie and tī kouka.

The best description of the process was preserved by that stalwart of Muruhiku customs Herries Beattie, writing in Traditional Lifeways of the Southern Māori.

Beattie says Muruhiku people soaked kāmahi bark in an ipu (a wooden dish) filled with water, into which hot stones were placed to boil the water. The liquid was left to cool naturally for two or three days and the resulting reddish dye produced a colour that lasted well. It was sometimes used as a preservative to soak fishing lines or to stain mats.

Early Pākehā settlers recognised the preservative properties of kāmahi bark, which has up to 30 percent tannin content. During the 19th century they used this natural resource to tan leather, and for a brief time the bark was exported for this purpose.

In Māori Healing and Herbal, Murdoch Riley lists only four recorded medicinal uses for kāmahi (Weinmannia racemosa) and its closely related cousin tawhero or tōwai (Weinmannia silvicola), a slightly smaller-leaved form found north of Auckland. Some records suggest the names tawhero and tōwai were applied to both species.

Riley records a member of a survey party near Waitōtara in the 1870s who burnt his leg stepping over a fire in front of his tent. The wound would not heal. A Māori chief by the name of Harawira took some bark from the tawhero, scraped off some of the reddish inner bark, made a poultice from it and applied it to the open sore.

“It was no time until a healthy skin covered the wound and in quite a short time my leg was alright,” the grateful patient wrote.

Similar treatments involved taking the clean inner bark from the sunny side of a tōwai. The bark was boiled and the liquid, sometimes mixed with olive oil, was applied warm to burns. The burns were reported to heal without leaving scars.

Similar treatments involved taking the clean inner bark from the sunny side of a tōwai. The bark was boiled and the liquid, sometimes mixed with olive oil, was applied warm to burns. The burns were reported to heal without leaving scars.

Other sources say bark taken from the west side of the kāmahi, from which the outer rind had been scraped off, was steeped in hot water and the brew imbibed to treat abdominal and thoracic pains. An infusion of the inner bark soaked in boiling water was also taken as a tonic and a laxative.

Modern science confirms the bark contains large amounts of tannin and catechin, which has astringent properties. In Which Native Tree? Andrew Crowe writes that chemical analysis of kāmahi leaves identified antiviral properties against influenza type A.

Naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander classified kāmahi when they collected samples from Queen Charlotte Sound during James Cook’s first voyage of the Endeavour.

Like many native trees kāmahi is hardy and will grow in most situations. It often starts life as a dense shrub, but, given the space, can develop into a handsome specimen tree. The bark is relatively smooth and is greyish in colour with blotchy patches of white.

The adult kāmahi has large, shiny, leathery leaves (3–10 cm long) which are oval in shape with a roughly toothed edge. From late spring to autumn the tree is festooned with flowers delicately arranged on fluffy white spikes, not unlike those found on some hebe species.

Both the flowers and the foliage make this plant popular with florists for use in formal flower arrangements.

The timber is difficult to season as it is prone to warping and cracking. The wood is light in colour and strong, but is not durable when exposed to the weather. Nonetheless, it was traditionally used for sleepers, piles for house construction and as fence posts.

The best way to appreciate this forest tree these days is to sample the very distinctive bush honey that beekeepers specifically target, particularly from the kāmahi forests on the west side of the Southern Alps.

If you can lay your hands on a sample of kāmahi honey before it is exported, it has a strong and distinctive taste that will remain in your memory for a very long time.