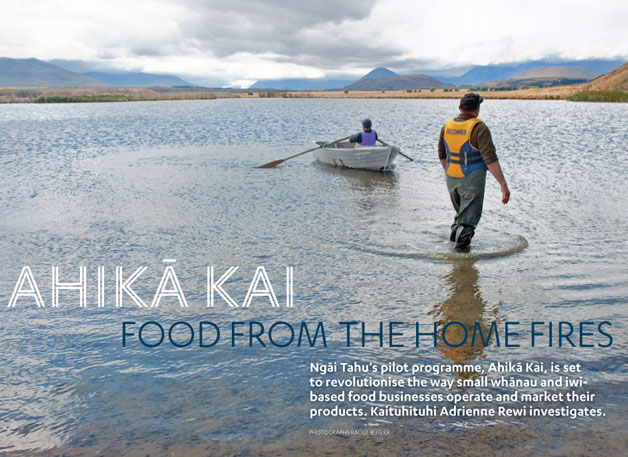

Ahikā Kai

Apr 19, 2012

When Robert Dawson was made redundant after 45 years at the freezing works, he didn’t hang about wondering what to do next. He wasn’t blessed with options, not after 45 years in a job he started straight from school.

But Robert (Ngāi Tahu – Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Ngāpuhi) comes from a long line of hunters and gatherers and he knew how to catch eels. So, with his wife Bev, he set up Moko Tuna. Initially he sold live eels to an exporter for $5 a kilo, but that was barely enough to pay for the gas he used getting around the countryside catching them.

Robert figured he could add value through smoking the tuna. By smoking the catch in a small food processing unit set up in his garage and selling it in branded 200 gram packs, the gross return increased to around $50 a kilo.

Robert figured he could add value through smoking the tuna. By smoking the catch in a small food processing unit set up in his garage and selling it in branded 200 gram packs, the gross return increased to around $50 a kilo.

Moko Tuna is actually three people – Robert, his wife Bev, and Mo Sullivan (Ngāti Whātua) – and between them they sell Moko Tuna packs at regional farmers’ markets around Christchurch every weekend, and to high-end restaurants.

They are good at what they do – last year Moko Tuna was named Best Food Producer from the River or Sea in the 2011 Taste Farmers’ Markets New Zealand Awards. But like any small business, finding time to market the product is tough. Just catching and processing the eels and heading to the markets every weekend eats away the hours.

Dawson hopes a pilot programme set up by Ngāi Tahu will change that.

John Reid (Te Arawa), regional economic development manager for Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, has been working with economic development leader Jymal Morgan (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Irakehu) on Ahikā Kai. The programme is set up provide a long-term avenue for small and medium-sized Ngāi Tahu enterprises to sell food products into an established market under the Tahu Kai brand. It is also intended to provide an opportunity for Ngāi Tahu whānui to purchase foods that are part of their heritage.

It is a simple idea. Small and medium food producers plug into an online marketing infrastructure that leverages the Ngāi Tahu brand and gains access to wider markets. Consumers order and pay online, the order is sent to producers to fill, and producers get paid once a month. All at no cost to Ngāi Tahu producers.

“There’s zero cost to whānau to be involved in this,” says Reid. “We are trying to simplify the business model for whānau. We act as a conduit. Customers simply order and pay online and we forward that order to the producer. They then send the product to the customer and we pay whānau producers once a month. We’re the administrative core.”

Ahikā Kai is a cultural revitalisation project as much as it is an economic project, say Reid and Morgan.

Ahikā Kai is a cultural revitalisation project as much as it is an economic project, say Reid and Morgan.

Ahikā Kai relates to food that has been harvested, fished, hunted, gathered and processed by Ngāi Tahu people living in their ancestral areas, following the traditional kaupapa of kaitiakitanga (guardianship). It refers to all food produced – from the traditional wild, harvested foods (mahinga kai) through to contemporary cropped or farmed foods.

In order to supply food under the Ahikā Kai label, Ngāi Tahu food producers must be accredited and adhere to the five key principles of production: hauora (health), kaitiakitanga (sustainable management), whanaungatanga (fairness), kaikōkiritanga (care) and tikanga (cultural ecological wisdom).

Their product is then sold with an individual provenance number, via a specialised website, direct to the customer. Buyers can go online to track their purchase back to its origin and read about the people involved in its production.

The Ahikā Kai programme taps into an international trend toward sustainability, auditing, branding and authenticating identity in food products, says Professor Hugh Campbell, head researcher at the University of Otago’s Centre for Sustainability, Agriculture, Food, Energy, Environment (CSAFE).

But the move toward indigenous branding is a relatively new international trend, and Campbell says it comes with the specific challenge of how food is authenticated and embedded with intangible values.

“The big question is, how do you measure tikanga? I think it can be done but we are in an experimental stage. Ngāi Tahu’s approach is significant in that they have established social networks and social authority ahead of a commercial launch, and they are using a depth of culture and tikanga that is already there.

“We have seen a few individuals nationwide leveraging off Māori cooking shows but the question is, where do you get your cultural authenticity from?

Campbell says the Ngāti Kahungunu project, the Aunty’s Garden website, is another brilliant idea. “The word ‘Aunty’ already has a cultural resonance but it’s different – it’s about connecting producers with buyers in a different way. Ahikā Kai is an exciting development, and it’s great to see Ngāi Tahu investing in this kind of initiative.”

Ahikā Kai currently has two operational producers online: Moko Tuna, and Wairewa Runanga-owned Te Pūtahi Farm (see sidebar) with their farmed lamb. Reid says a number of new products will soon be coming online, including tītī (muttonbirds), Kaikōura pāua and freshwater kōura, with others in the early planning stages.

Ahikā Kai takes all the hard work of small business away from the producers, says Jymal Morgan. “Many small Māori businesses struggle because they don’t have the business networks, the capacity or the marketing skills. We do all that for them. We streamline the whole process so they can focus on what they do best. It’s a great opportunity and we’ve already been approached by several whānau.

“A lot of people have to see something in action before they can believe in it and take the ideas on board. By setting up the pilot we can show people the scheme has merit and value. It’s about getting the word out there too and trying to overcome that tall poppy syndrome that sometimes pops up at a whānau level.

“The opportunity is there for everyone, and we’ve put good business governance structures in place; and we have specialist skills to help guide the development of the business and the processes.”

Robin Wybrow, chairman of Wairewa Rūnanga, believes the Ahikā Kai programme is a great way for Ngāi Tahu to express one of the most important elements of Te Kerēme (the Ngāi Tahu Claim) in a contemporary sense.

“This will potentially position Ngāi Tahu both nationally and globally in terms of food and who we are,” says Wybrow. “Mahinga kai was and still is the currency of our people. It’s all about manaaki, about looking after people; so the quality and quantity of food we can produce is a reflection of our mana.

“It also reinforces our trailblazing image in terms of iwi innovation, and it will encourage others to think about how they market their food. Other iwi are engaged in food products – Ngāti Porou has its mānuka honey and other iwi are involved in dairying, but I don’t think it’s in the same context as this – not in terms of provenancing and online sales. There’s great potential here. The only real challenge will be fulfilling the market.”

The demand for ethically produced, traceable food is increasing, as consumers want to know where their food comes from and how it has been produced, says John Reid.

“The early response has exceeded our expectations, and we’re still in the pilot stage. The key for us is getting the food quality right before we launch with advertising. The products have to be perfect to capture the highest value possible.”

One problem for small producers can be the ability to satisfy demand. “We’re working closely with producers to identify any problems and we’re developing strategies to combat them,” says Morgan. “We already have someone who can take all the lamb we can produce, but the project was developed to supply whānau with traditional kai. So far though, there’s been more interest from high-end foodies and restaurants, so getting the price right is another challenge. We could ask more, but the price needs to be right for whānau.”

Morgan believes Ngāi Tahu is ahead of the curve in its Ahikā Kai business systems. “Creating direct food producer access for customers via the internet is the way forward and few people are doing it. Eventually, in the Rolls Royce version, products will be given a GPS code that customers can track on the website using Google maps to see exactly where their food has come from. At the moment, it’s a bit looser than that – more, this area rather than this river,” he says.

The traceability aspect of the project has a strong similarity to Ngāi Tahu’s pounamu certification scheme (www.authenticgreenstone.com). This features a tracking system to ensure that legitimately sourced Ngāi Tahu pounamu is easily recognised and respected. In the same way that customers can log on to the site with a traceability code supplied with their pounamu purchase, Ahikā Kai customers will be able to check the origins of their food products.

“Whether it’s food or stone, traceability and verification are the main issue for us,” says Morgan. “The cultural authenticity of both provides a link to the people, and builds ownership and capacity into local communities.”

John Manhire, programme leader for the Agriculture Research Group on Sustainability (ARGOS), a joint venture between Lincoln University, the University of Otago and the Agribusiness Group, says provenance setting has been common in Europe’s wine industry for more than 100 years, but he believes Ahikā Kai is different in terms of its New Zealand context and its reference to indigenous values.

“We have Te Waka Kai Ora (Māori Organics Aotearoa), but that’s an incorporated society promoting organic standards. It’s not the same as Ahikā Kai. What you have here is an integrated process of certification, marketing support, promotion and a traceable path back to growers. It’s a very holistic programme and it’s an excellent pathway for Ngāi Tahu to promote an incredible range of traditionally important food products to a wider market. Not only is it a very good business model for small businesses to sustain themselves through accessible markets, it’s also a very good way for local rūnanga to celebrate the variety and quality of iconic Ngāi Tahu kai and to provide iwi members with access to iwi food.“

John Reid is confident that people will select a Ngāi Tahu product on the basis of its provenance. “Ngāi Tahu has a strong, spiritual relationship to the land, and strong values associated with kai production. A lot of people in the organics world would love to have that level of connection. Not many products can claim it, and that’s what makes Ahikā Kai special. That’s a strong point of difference for us. People now want to know what they’re eating, and we can back up our claims of where and how our food has been produced.

“We’ve spent a lot of years dreaming about this and it’s very satisfying to see it finally coming together. It will go a long way towards helping grow, support and assist the development of the regions at a whānau and papatipu rünanga level.”

Rex Morgan (Ngāi Tahu, Te Arawa), the widely-known chef and owner of Wellington’s upmarket restaurant, Boulcott Street Bistro, frequently uses tītī, karengo, kawakawa and horopito in his French cuisine and says there is a huge potential for traditional kai.

“We find international visitors are more interested in traditional Māori foods than locals and they like to hear the stories behind the food.

“I’m a French-trained chef, so when I use traditional ingredients it is more about a Māori influence. People love our smoked salmon with karengo for instance.

“For me, as a Māori, it’s a very personal thing and when you work with traditional kai it’s important to treat it with respect.

“It’s still largely an untapped market though, and if the price is good and we can educate more customers, I think Ahikā Kai has a great future.”

And it feels right, says Robert Dawson. “It has a grassroots feel rather than a big corporate feel and our old traditional hunting and gathering philosophies are showing through. I’m very proud to be part of it.”