Attitude matters

Mar 31, 2019

In November 2018 Colleen Brown (Ngāi Tahu – Ōraka Aparima) was inducted into the Attitude Hall of Fame at the Attitude Awards, an annual ceremony celebrating the achievements of New Zealanders living with disabilities. Colleen received this honour in recognition of her contribution to the disability sector over the last 38 years, and is determined to use the award to continue to fight for equality and inclusion – and she is calling on her iwi to support her. Nā ANNA BRANKIN.

Above: Colleen Brown celebrating with her son Travers after being inducted into the Attitude Hall of Fame.

“I want to use this wonderful award very constructively for change,” Colleen says. “I feel very strongly about the huge challenges faced in the disability sector by whānau. It is exhausting, marginalising, and defeats even the most resilient of people.”

Colleen knows all about these challenges. She and husband Barry have four adult children and six mokopuna. Their second child, Travers, has Down syndrome – a genetic disorder that occurs when cells contain an extra chromosome number 21, causing delays in learning and development.

“When you have a disabled child, the lesson you learn very early on is that they are marginalised – that they don’t fit, even though they’re just a baby who needs nourishing and care,” Colleen says. “Nobody looked at Travers’ gifts – they looked at his deficits. You can easily marginalise people when you refuse to look at what they have to offer. But we were determined that Travers would have as good and cherished an upbringing as all our other children.”

This determination has paid off. These days, Travers is thriving. He flats with three of his friends. He goes to the gym, where he cleans the staff facilities in exchange for a discounted membership. He volunteers at a local op shop and has recently joined a tenpin bowling league.

Colleen describes it as a wonderful life, and one that she didn’t necessarily envisage when she first became aware of the challenges associated with his diagnosis. When she realised that Travers – and other children living with disabilities – were going to face prejudice and exclusion throughout their lives, her “social justice identity” came to the fore and her voluntary career as a disability advocate began.

“I’ve always been a very positive person, and I’ve always been quite articulate,” Colleen explains. “I think if you combine those things with a campaign, or a strong sense of what is right, then you can create change.”

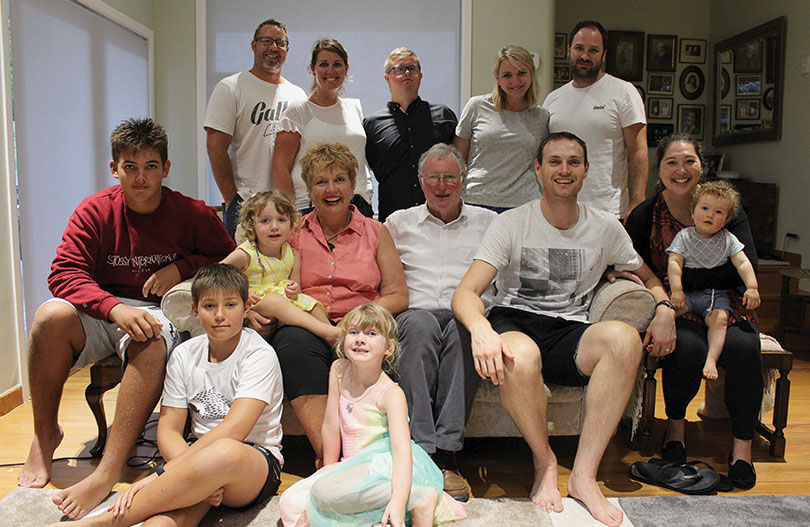

Above: Colleen and her whānau. Back row L-R: Olivia Brown, Travers Brown, Julia Finlayson, Asher Finlayson. Middle row L-R: James Brown, Emma Finlayson, Colleen Brown, Barry Brown, Jordan Brown, Grace Brown, Ryan Brown. Front row L-R: Cameron Winiata-Brown, Kate Finlayson. Absent: Georgia Brown.

Over the last 38 years, Colleen has created change by helping to found and chair the New Zealand Down Syndrome Association. She also holds senior governance positions in local government, the disability sector, and health; and is currently serving her fourth term as an elected member of the Counties Manukau District Health Board. She has completed her Master of Education and has published numerous reports on disability and education, and today chairs a number of community-based boards and organisations including Disability Connect, a support service for families based in Auckland.

“It is time we stood up collectively and put a stake in the ground. The Prime Minister says her focus is on children – well, let’s focus on those children! What are we doing about the fact that many of the children in the care of Oranga Tamariki are Māori? What are we doing about the fact that most special schools are full of Māori boys? What are we doing about the fact that many Māori families are not receiving child disability allowances?”

Colleen Brown Ngāi Tahu – Ōraka Aparima

What drives her? A determination to make sure every child living with a disability has the same opportunities that she was able to give Travers.

“I have a background in teaching, I’m well-educated, I have support and contacts that I’ve built up over the years,” Colleen says.

“What if you’re a single parent living in a poorer area, who doesn’t understand the system? How do you take on the might of the Ministry of Education?”

Often, the answer to that question has been “go and see Colleen.” If a disabled child is declined enrolment to school or not provided with enough funding, the parents can take a case against the Ministry of Education under Section 10 of the Education Act 1989. Over the years Colleen has worked with parents on a number of Section 10 appeals, a time-consuming and frustrating process that has opened her eyes to the shortcomings of the system – and in particular, to the negative statistics that affect Māori whānau.

Above: Kiringāua Cassidy with parents Komene Cassidy and Paulette Tamati-Elliffe at the recent Attitude awards.

A report released in 2014 by the Disability Convention Independent Monitoring Mechanism found that there was social exclusion and poverty, particularly among disabled Māori and Pasifika children. It also found that Māori children with disabilities have greater difficulty accessing some government services, including health and education services.

These findings are in keeping with what Colleen has witnessed throughout her involvement in the disability sector, and she is challenging Ngāi Tahu to create a solution to this systemic problem.

“It is time we stood up collectively and put a stake in the ground,” she says. “The Prime Minister says her focus is on children – well, let’s focus on those children! What are we doing about the fact that many of the children in the care of Oranga Tamariki are Māori? What are we doing about the fact that most special schools are full of Māori boys? What are we doing about the fact that many Māori families are not receiving child disability allowances?”

“Kiringāua isn’t suffering from his disability. He’s living with it. If anyone is suffering from their disability, then that’s an issue and we should address it. That’s part of educating whānau and hapū – to understand that everyone has different challenges that affect their lives. For some people that challenge is a disability, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Komene Cassidy Father of Kiringāua Cassidy (Ngāi Tahu – Ōtākou), who has spina bifida

For Kiringāua Cassidy (Ngāi Tahu – Ōtākou), these statistics are a reminder to appreciate the support and opportunities he has had. The 16-year-old has spina bifida, a structural defect in the base of his spine and has used a wheelchair since childhood.

Much like Colleen and Barry, Kiringāua’s parents – Komene Cassidy and Paulette Tamati-Elliffe – have endeavoured to give Kiringāua the same opportunities as the rest of their children.

“We never really thought about the things that Kiringāua couldn’t do,” says Komene. “It was more about making sure he was confident and independent in the things that he could do – which is really how all kids should be raised.”

Like Travers, Kiringāua is thriving. He was a finalist at last year’s Attitude awards in the Youth Spirit category. He is currently training in the hope of being part of New Zealand’s ski team at the Winter Paralympics in 2022. He is a fierce kapa haka competitor, and last year placed second in the Junior Māori category of Ngā Manu Kōrero, the national speech competition.

“Growing up in te ao Māori with a family that supports me means I’m pretty grounded – I know who I am and where I come from,” Kiringāua says. “I’d like to see Ngāi Tahu reach out to those whānau who aren’t as connected, to give them the same opportunities that I’ve had. But the biggest thing I’d like to see is a change in mindset – if Ngāi Tahu could change the way people think about disability I’d be very happy.”

Komene agrees, saying that a change in attitude is critical to addressing prejudice in the disability sector. “Language is a big part of it. Kiringāua isn’t suffering from his disability. He’s living with it. If anyone is suffering from their disability, then that’s an issue and we should address it,” he says.

“That’s part of educating whānau and hapū – to understand that everyone has different challenges that affect their lives. For some people that challenge is a disability, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Above: Kiringāua pursuing his dream of qualifying for the New Zealand ski team at the Paralympics.

According to Colleen, prejudice towards the disabled community is rarely malicious, and usually comes down to a lack of awareness. Recently she has been astounded by the fact that houses are still being built in Aotearoa that don’t have toilets on the ground floor. “If we as a country wanted to be totally inclusive, that wouldn’t happen,” she says. “Think about the child with a physical disability sitting in class when the birthday party invitations are handed out. If that home doesn’t have a toilet downstairs, they may not be able to go – and that is a re-disabling of that child.”

When it comes to changing the national attitude towards disabilities, Colleen is matter-of-fact. “Yes, inclusion is a mindset. But it is also a human right. It’s time for Māori to stand up and say, ‘We are absolutely and utterly claiming this human right. It is for us, it is for our whānau, and we will invest in that’.”

For Colleen, that investment needs to be in addressing the key challenges of accessibility and poverty. “Ngāi Tahu has got to capture the most marginalised of our whānau – and those are our whānau who are affected by disabilities,” she says. “We need to ask these families what support they need most – whether it’s advocacy, social work, or funding. In the disability sector we have a saying: nothing about us, without us. It’s the same for Māori – we need to create a solution that is held by Māori, for Māori.

“Ngāi Tahu has to lead this discussion. The thing that Ngāi Tahu has to offer all of its parents is hope – that somebody cares, and that we’re listening,” Colleen says.

“If we can save one family heartbreak and anguish, then we’ve done a good job. But imagine if we can save ten, twenty, thirty – a hundred. Wouldn’t that be worthwhile?”