Aukaha

Dec 19, 2022

Ko Hikaroroa tōku mauka

Ko Waikouaiti tōku awa

Ko Āraiteuru tōku waka

Ko Kāti Huirapa tōku hapū

Ko Kāi Tahu rāua ko

Ngāti Kahungunu ōku iwi

Ko Ōtepoti tōku kāika

Ko Moewai Rauputi tōku ikoa

The art of staying connected

Hidden between mānuka”, painted with whenua pigments.

For Moewai Rauputi Marsh, the importance of connectivity with others, with the whenua, and with her whakapapa is what drives her in the creation of her art. Kaituhi Hannah Kerr caught up with her to discuss her art journey and her goals.

Moewai grew up in Ōtepoti, Dunedin, briefly living on Shetland Street by Āraiteuru Marae with her grandparents. “I have whānau spread out all across the country and whānau in Australia too, but most of my immediate whānau are all here in Ōtepoti.”

Moewai laughs when I ask her what she loves about Dunedin and why she has stayed here. We joke about our home city being a bit boring and as teenagers all we wanted to do was get out. But it’s home. Moewai smiles, “I love that my whānau are here, heaps of my mates. I love that I’m part of creative communities, Māori communities.

Moewai Rauputi Marsh at Puketeraki gathering whenua.

I love the pace of the city, the landscapes. The beaches, the peninsula every bit of whenua I see is home and all of it is so special.”

Moewai and I met in what we agreed feels like a previous life. We went to school together, but being a few years apart, the only time we crossed paths was on her Year 10 te reo class’s Arapounamu tramp on the Milford Track in 2013. The kaiako, Matua Tim Lucas, invited me and two others to attend as tuakana.

I asked Moewai what she remembered about the trip and whether it sparked anything in her that comes out in her art today. “I remember feeling tired and sore,” she laughs. “I felt so present with all of my surroundings and so peaceful.”

There’s a pause, transporting us back to memories of waterfalls rushing down cliff faces, the song of manu in the bush around us. It was a type of tranquility you don’t feel in everyday life. “That’s how I feel within my practice – working with the whenua takes me back to those feelings of true contentment and how wonderful those feelings are. If I walked it again I’d love to paint there, maybe gather some whenua, and see what colours I could find.”

During art classes at school, her work was bright and colourful, inspired by artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. It was what they taught in school so she assumed it was the type of art she liked.

After high school, Moewai attended Dunedin School of Art and it was here in her final year she knew she wanted to express herself as a Māori artist. “But there are so many Māori artists, I wanted my own voice.

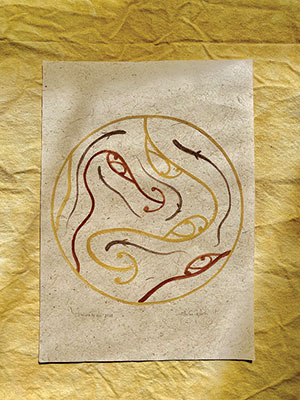

“Tiakina te Wai”, whenua pigments on harekeke paper.

I didn’t want to copy other people; it was about trying to figure out who I am, what’s my connection to my whakapapa, to my Māoritaka. I was pretty isolated, just trying to figure it out on my own.” So she decided to sign up to the Level 3 Mahi Toi course at Te Wānanga o Aotearoa.

It was the first time she was surrounded by other Māori doing traditional Māori art. It was at this point she realised “Māori art is not so much what I create myself, but the connections that you make with other people. You get inspiration from everyone you surround yourself with; they help you to shape your voice. So I’ve just stuck with that community ever since.”

While prioritising her art, Moewai also works at Artsenta Dunedin, which is an award-winning art studio for people who use mental health and addiction services. They provide a range of free creative activities and resources for people to try.

Before getting this role, she says she had a brief stint working in the shearing sheds with her mum and stepdad. “It was so hard. Physically and mentally draining. The money was mean but the work wasn’t and I had no energy to do my art. So I quit after realising I wanted to do art full-time,” she says. “I don’t regret it though; it was a really good learning curve and I stayed with my mum and stepdad every night so it was nice to spend quality time with them.”

While we chat, we realise we keep circling back to one main theme: connectedness. Every question I ask, we somehow wind back to discussing how important it is to stay connected with our iwi of Kāi Tahu, with people we have met along our respective journeys (including each other), and sharing knowledge that others have shared with us.

However, connectedness must come with boundaries, and that is something Moewai admits has been a challenge. She lives a busy life, working 30 hours a week in a job that requires a lot of creative energy. She also dedicates time to her mahi toi studies, attending noho during weekends, works on commission mahi, and creates art for herself.

This means Moewai gives a lot physically, emotionally, and mentally to her communities.

Whenua pigments gathered across Ōtepoti, underneath the work “Tiakina te wai” – this was a part of Moewai’s final mahi for her mahi toi class exhibition.

When she doesn’t have the right boundaries in place, she gets stressed and it starts to affect her mental health. Going through these waves can be exhausting. “I am learning, slowly, how to say ‘no’. I’m learning not to give all my time and energy away so I still have something left for me and my practice. I’m also learning to put myself first and that can be the biggest challenge as an artist as it’s so easy to people please and put other people before yourself.”

Most artists paint with oil or watercolour, but Moewai has been making paint out kōkōwai collected from Puketeraki and Ōtākou. As well as gathering kōkōwai she has also started to gather other pigments from Ōtepoti landscapes that connect Moewai to her whenua.

The idea came when she was involved in the Paemanu Tauraka Toi – A Landing Place exhibition at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and met curator Nathan Pohio.

“He was amazing. We developed a friendship and then found out during the process of creating for Paemanu that he is my uncle. It was really special.

He encouraged me to connect with each of my rūnaka, start creating relationships with them. So I made a lot of scary phone calls and emails saying, ‘Kia Ora I’m Moewai, I want to do some art, but I don’t know what I want to do yet. Can I come say hello?’,” she laughs. “But they were all amazing.”

Moewai has whakapapa connections to Puketeraki, Ōtākou and Āraiteuru marae and was invited to visit each rūnaka.

She began walking around each place, listening to kōrero about different areas.

“It was really beautiful to just sit and listen to the stories of my tīpuna.”

When visiting Āraiteuru Marae a few doors down from where she grew up, she mentioned wanting to gather some kind of whenua. They offered harakeke, but Moewai opted for gorse and stinging nettle. She had been learning how to make paper at work and wondered if there was a way to make it with invasive plant species.

“Orokohanga”, whenua pigments on stained unstretched canvas (stained with kōkōwai.

Then she headed north to Karitāne and Puketeraki marae, where she connected with Suzi Flack. “She’s amazing, such a beautiful soul.” After asking for permission from Kāti Huirapa ki Puketeraki Rūnaka to gather kōkōwai from the whenua and outlining her intention that collected whenua would be used for connectivity to her iwi and in artwork to be displayed in the Paemanu Tauraka Toi show, Moewai joined Suzi on a hīkoi to Huriawa Pā.

“She shared stories with me about where our waka ended up, where our ancestors travelled to, what each of the awa were called, all these things I had no knowledge of. It was incredibly special to learn these histories. I feel so grateful to Suzi to allow me to have that experience with her and to help me connect more with my whakapapa.

“I often felt intimidated going to my marae. You feel like an intruder, worrying that people think you don’t belong here, or you’re just one of those people who’s there for the food,” she exclaims, shaking her head with a grin. “When I made that connection with Suzi, I realised this is a place of belonging. I stood there on the whenua, dirt in my hands, the stories of our tīpuna surrounding me, and I felt really safe.”

Bridget Rewiti is another Kāi Tahu artist who Moewai has connected with, and who has also been using kōkōwai in her work. Bridget taught Moewai how to make the whenua into paint.

“To make it into a paint you can use different binders. A traditional binder you can use is shark oil, whale oil – Bridget was using linseed oil. I then use a mortar and pestle to crush the dirt, and I have been using kauri gum, or the traditional binders of shark or whale oil, all of which I have been given. Then a little bit of honey and water, which turns into a beautiful paint.”

Using this knowledge and the collected whenua, Moewai created Tūturu, which was part of the Paemanu Tauraka Toi exhibition. “I had my handmade paper of gorse and stinging nettle from Āraiteuru, and all my whenua from all my landscapes that I connect to at Puketeraki and Ōtākou that was painted on the paper.”

Moewai also attributes her growing knowledge and experience to Kauae Raro, a research collective that share mātauraka around using the whenua as an art material. “They have contributed so much mātauraka for my kete and I want to thank them for everything they have taught me.”

While Moewai is unsure where her career is headed, one thing is certain: she is very sure of her purpose and why she does what she does.

If you want to keep up with Moewai’s journey, her Instagram is a good place to start (@moewaimarsh_art). “Honestly, the best way to see my work is by getting to know me; my work is a reflection of me and my journey connecting to my Māoritaka and sharing the things I love.”

Waiho i te toipoto, kaua i te toiroa –

Let us keep close together, not wide apart.