Best person for the job

Oct 5, 2017

He Whakaaro

Nā Ward Kamo

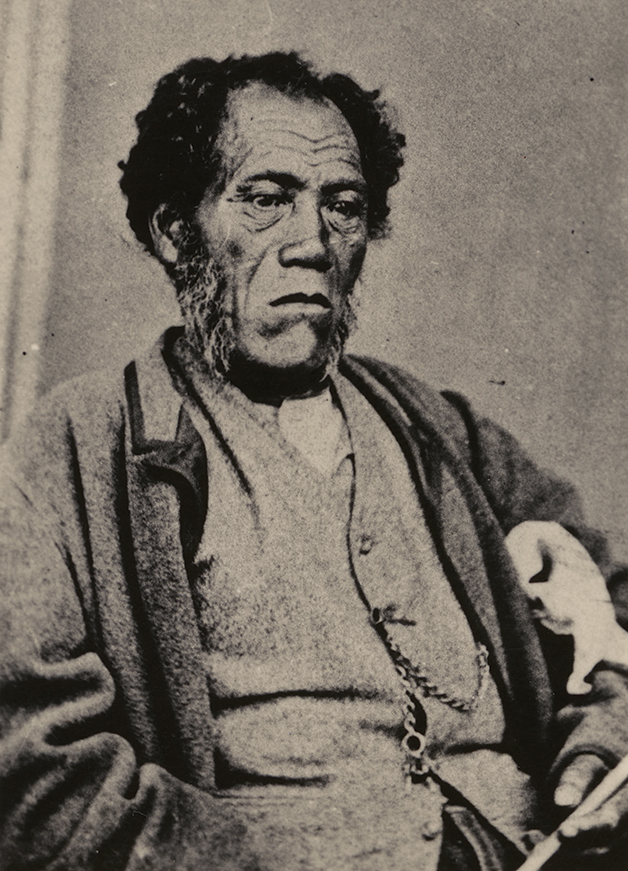

“This was the command thy love laid upon these Governors. That the law be made one, that the commandments be made one, that the nation be made one, that the white skin be made just as equal with the dark skin. And to lay down the love of thy graciousness to the Māori that they dwell happily and that all men might enjoy a peaceful life and the Māori remember the power of thy name.” (Matiaha Tiramōrehu – Letter to Queen Victoria 1857)

These famous words from our tupuna Tiramōrehu sum up our ongoing struggle for recognition and equivalency for the past 175 years. Ngāi Tahu have held firmly to the desire that Pākehā should be equal to Māori.

Our long-standing Treaty grievances with the Crown were resolved through the passing of the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Act 1996, and then the Ngāi Tahu Settlement Act in 1998. Twenty years later we have turned a $170m settlement into a $1.3b taniwha. This pūtea enables a dividend of around $50m to be paid to the tribal representatives for distribution to various Ngāi Tahu development initiatives. The commercial standing of Ngāi Tahu in the corporate sector is second to none.

Underpinning this financial success has been a firm adherence by the tribal representatives to the policy of “the best person for the job”. If we return to the words of Tiramōrehu, “… that the white skin be made just as equal with the dark skin …”, this policy fits perfectly; at least at face value.

Why “best person for the job”? Well the history of Ngāi Tahu is long – far longer than the magical year 1840. Yet it’s that year and the subsequent 25 years that saw Ngāi Tahu go from the sole owner of 80% of Te Waipounamu to virtually landless. The history of this loss is well documented and well understood.

The loss was unlawful, unconscionable, and unquestionable; and this wasn’t lost on the Crown at the time. Subsequent efforts to recover that which was promised were either ignored, legislated against, or just “forgotten about”. Given that ethnographers were predicting the elimination of Māori, the “stick your head in the sand” policy was politically expedient.

It was not until 1991, with the immortal words of the Waitangi Tribunal “… that in acquiring from Ngāi Tahu 34.5 million acres, more than half the land mass of New Zealand, for £14,750, and leaving them with only 35,757 acres, the Crown acted unconscionably and in repeated breach of the Treaty of Waitangi” that redress for the staggering loss of land would commence. And the rest, of course, is history.

Or is it?

The quote about “skins” from Tiramōrehu is about equivalency. It is not about homogeneity. The efforts by Tiramōrehu and subsequent rangatira clearly indicate the Ngāi Tahu desire to remain “Ngāi Tahu”. It was about an economic and social base in which to engage the world equal with the “white skin”.

The desire to find “the best person for the job” is Ngāi Tahu pragmatism. It recognised, with a once-small base, that we needed to look to wherever the skill lay to run the pūtea on behalf of our iwi. That began with Sid Ashton’s appointment as first CEO. But it’s only half the story. “Best person for the job” was also a political stance. It sought to defy the expectation that Māori were too immature to handle large sums of money, that we’d drink our settlement, make terrible investment decisions, and generally muck up. But the policy also divided Ngāi Tahu. Some predicted it would see the Iwi lose control of its own affairs. It has proven detractors both right and wrong.

What are we saying to our Ngāi Tahu people every time we reject them for a role and then hand that role to a non-Ngāi Tahu? They are not the best people to work in their own organisation? We need to be careful of disempowering ourselves with our own words.

But 20 years since settlement, we must ask the question – has the policy now served its purpose? Shouldn’t the true measure of the “best person” policy no longer be our financial success, but the confident appointment of Ngāi Tahu to management roles?

Across Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu boards we have 55 directors, of whom 42% are Ngāi Tahu. Frankly, that’s not a particularly egregious percentage. However, across Ngāi Tahu Holdings (NTH) the numbers depart more dramatically. Just 35% of our boards are Ngāi Tahu. Clearly Ngāi Tahu have a fair way to go before they are considered “best people”.

Meanwhile, our wāhine make up just 22% of our appointed boards. For NTH that number drops to 19% across all boards. Our 1000-year history is replete with Ngāi Tahu overcoming considerable odds to survive and thrive. From the decision to leave Whāngārā, the decision to leave Te Whanganui-a-Tara, and move south, to the eventual establishment of our powerbase, Ngāi Tahu people made the decisions for better or worse. And wāhine were integral to that. How many of us descend from the great Ngāi Tahu wāhine Tūhaitara and Irakehu? Can it really be that only 20% are capable of being on our boards in this day and age? I’m not so sure about that.

Dr Eruera Prendergast-Tarena (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau a Apanui) succinctly challenges the “best person for the job” policy when he says:

““Best person” can be the most marginalising two words in our language if it’s not grounded in our reality and culture or recognising our strengths …”

What are we saying to our Ngāi Tahu people every time we reject them for a role and then hand that role to a non-Ngāi Tahu? They are not the best people to work in their own organisation? We need to be careful of disempowering ourselves with our own words. The narrative of “best person” must be rejected, and quickly. That doesn’t mean rejection of non-Ngāi Tahu who want to work for us. We should be as embracing of our tauiwi as we’ve ever been.

But the broader question is: how much of our identity and cultural expertise is incorporated into our requirements for those who wish to serve us? We should be asking applicants whether they have knowledge and understanding of our tikanga as part of their suite of skills. Why isn’t this at the forefront of every role we seek to remunerate? Are we still hesitant to assert our identity as Ngāi Tahu both externally and internally?

At $1.3b in wealth we now have the economic and political clout to set the agenda for ourselves. We should wield that political and economic capital for all it’s worth. We have more than 150 years of marginalisation to overcome. We should take an unashamed stance on what’s important to us as Ngāi Tahu, and ensure that is reflected in the people who work for us.

With at least 58,000 people who identify as Ngāi Tahu, we can and should take a more dominant role on our commercial boards and in our commercial management. Tiramōrehu wanted equality for the “skins”. But I’m pretty sure he never thought those words might have to be applied within Ngāi Tahu.

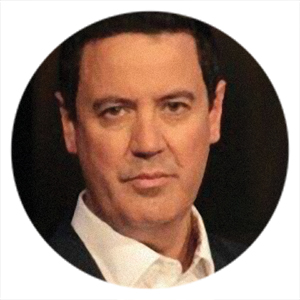

Ward Kamo (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mutunga Chatham Island, and Scottish decent) grew up in Poranui (Birdlings Flat) and South Brighton, Christchurch. Leaving University with a BA and PG Dip in Natural Resources, Ward’s career path has been varied, at times eye raising, and ultimately rewarding.

He has worked with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (Ngāi Tahu Holdings Corporation), and the Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri Iwi Trust as General Manager. He is currently working with Bayleys as National Director of Tū Whenua – the Bayleys Māori business division.

Ward will be a regular columnist in Te Karaka offering a perspective on issues and politics of significance to Māori.