Breaking the silence

Jul 7, 2016

Despite a shift towards more open conversation about self-inflicted deaths, New Zealand’s suicide rates continue to rise and Māori men feature all too prominently in these statistics.

Kaituhi Beck Eleven reports.

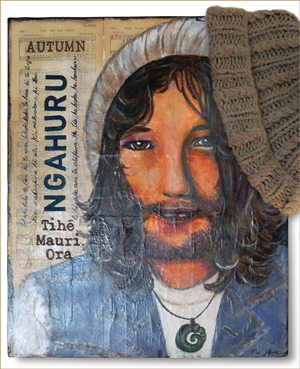

Nicky Taiaroa Macpherson Stevens wore a pounamu around his neck until the day it was removed from his lifeless body.

Nicky Taiaroa Macpherson Stevens wore a pounamu around his neck until the day it was removed from his lifeless body.

It was a gift from his mother and it had been blessed for spiritual protection. Nicky (Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Toa Rangatira) wore it every day but it wasn’t enough to stop him from taking his own life.

Now his family are speaking out about mental health, hoping to reduce the whakamā around suicide.

Speaking from her Ngāruawāhia home, Jane Stevens says she and her husband Dave, a Hamilton city councillor, believe their son’s death was entirely preventable.

They believe his care was not adequate, and that spiritually-based, Māori-focused treatment would have helped him immensely. Since Nicky’s death, they have doggedly pursued legal avenues to find some justice.

Meanwhile, they feel that breaking the silence and shame associated with suicide, in particular the over-representation of Māori in suicide statistics, is one way they can honour their son.

“It’s so raw and so personal,” Jane says.

“I know I can’t bring Nick back but there is one thing I can do and that is speak out. I can only contribute by trying to break the silence and the whakamā around mental illness.

“If I achieve that, then I have honoured my son.”

The government’s New Zealand Suicide Prevention Strategy 2006–2016 states that the suicide of a single person can have a long-lasting and profound effect on family, friends and the wider community.

“For Māori, the grief and impact is often felt beyond the whānau to the hapū and iwi, viewed not only as a tragedy, but also as a loss to the continuation of whakapapa,” the report says.

Last year, 569 New Zealanders died by suicide or suspected suicide – almost twice the nation’s average road toll.

In last year’s budget, a small increase of $2.1 million in new funding was allocated for rangatahi Māori suicide prevention.

2011 figures show that the Māori suicide rate was 1.8 times higher than non-Māori, while the rate of Māori youth (classed as 18–24 years old) was 2.4 times higher than non-Māori youth, and heavily weighted towards males. Māori of both sexes also have a higher hospitalisation rate for suicide attempts compared with non-Māori.

The Stevens whānau at the unveiling of the seat dedicated to Nicky’s life, placed on the banks of the Waikato River at the spot where he found peace. Left to right: Dave with moko Johnny, Tony’s partner Georgie, Tony, Jane with moko Fallon.

Other studies have shown that the suicide rate drops significantly for adults aged over 45, and suggest older Māori may be more valued and have more meaningful roles and status compared with older non-Māori people.

Jane believes a “culturally-based, whānau-based support system” would have benefitted her son.

“We didn’t want a mainstream system. We didn’t feel that was appropriate for Nick.

“I feel completely failed by the Kaupapa Māori community mental health service that we had, that turned out to be a shadow of a mainstream service. It was underfunded and didn’t work in a culturally appropriate way because of structures and not having people with the skills to do it.”

Risk factors for suicide include stress, mental distress and illness, childhood adversity, genetic and social risk factors, unhappy relationships and family violence. Other triggers can be bullying, drug or alcohol abuse, loss of peer acceptance, or a romantic break up.

Nicky was found dead in the Waikato River on March 12 last year. He had last been seen on March 9 leaving the Henry Bennett Centre in Hamilton, where he had been placed on a compulsory care order under the Mental Health Act.

He had been allowed to go out on the street for cigarette breaks, but his family were firmly against Nicky being outside on unescorted leave. They knew he was in a dark place and had tried to take his own life several times over previous days.

Jane says it breaks her heart reviewing CCTV footage showing her son going in and out of the centre, “clearly agitated and in deep distress.”

“There is no mistaking it – he was confused and in need of help but no one, not even staff who walked past him in the main foyer, stopped to help him,” she says.

“There is a problem with the types of treatment, the politics around it, funding of services, and problems with the level of skilled clinicians. It’s a train wreck, a total train wreck. People get put in cells by the police instead of being given the help they need. That kind of thing was Nicky’s future.

“Even working with a Kaupapa Māori service, Nicky still had [people of other cultures] who had no hope on the planet of understanding. In contrast, when we first went to the service he had a Māori nurse, a Māori support worker and a Māori doctor and he did well.

“They left and they grabbed who they could. On reflection, that was hugely significant.”

Given her experiences, Jane says she would like to see a mandated whānau-centred approach to mental healthcare, which includes the wider whānau.

Given her experiences, Jane says she would like to see a mandated whānau-centred approach to mental healthcare, which includes the wider whānau.

“Mainstream services try to say that not all whānau are healthy or helpful, and a lot of the time they actively exclude whānau because it’s easier not to include whānau as part of the picture.

“Yes, there are dysfunctional whānau and ones that are totally burnt out by the behaviour of the person, but because they are not getting the right support, they can’t cope.

“Which is why the ‘not one size fits all’ model works, because not everybody is the same.”

Nicky was diagnosed with schizophrenia, characterised by incoherent thoughts and behaviour. He had his first mental health experience at 15 and his first psychosis at 19.

“In Ngāruawāhia the socio-economic demographics reinforce just about all the bad statistics there are – lack of housing, education, health, crime – our people are already consigned to the bottom of the heap. We are already fighting to regain our mana and socio-economic wellbeing.

“If you have no hope and generations of struggle, it’s not rocket science to see why our young people are not seeing a future for themselves.”

“How we support each other is really important. Suicide is such a culturally sensitive issue in Māoridom. It’s so delicate and some attitudes don’t help that. Holding men up to be staunch, hard warriors when they might be suffering. My son was a warrior but he was a warrior of a different ilk. He was a modern warrior and he thought deeply about the world.”

Jane Stevens

Jane says that since talking publicly about her son’s suicide, she has heard from other families who have been through similar trauma.

“And that strengthens the resolve of our whānau to see change happen.

“We need awareness campaigns with teeth. Ones that have accessible services on the end of them, not just phone numbers.”

The couple see themselves continuing to advocate for Māori with mental health issues, and have already spoken on various panels and held a public forum to start people working together across the country.

Jane says she finds it uncomfortable criticising Ngāi Tahu with all the iwi continues to achieve, but feels she would like to see more leadership around mental health and suicide.

“We were supported by Ngāi Tahu to take Nicky’s kawe mate on to Tūrangawaewae Marae and to the Hui-ā-Iwi in Dunedin. This was a hugely significant part of our healing, however, nobody talked about what had happened to Nicky or the battles we have had to get answers since then.

“I’m used to people in my community not being able to say something because they find it hard, but I didn’t expect it from my own iwi and from our leaders. I guess I had really hoped that they would know what to say and how to support our whānau. I was looking for wise words but everyone was whakamā about how he died.

“How we support each other is really important. Suicide is such a culturally sensitive issue in Māoridom. It’s so delicate and some attitudes don’t help that. Holding men up to be staunch, hard warriors when they might be suffering.

“My son was a warrior but he was a warrior of a different ilk. He was a modern warrior and he thought deeply about the world.

“Ngāi Tahu have come a long way but a lack of connection to a strong and cohesive sense of identity takes its toll.

“As a parent, I don’t feel Nicky was culturally grounded enough to be able to stand tall, and I think for a lot of us living in the North Island it’s hard to know how to connect effectively.

“I am used to being the pale-face in the room and I don’t care because I know who I am, but Nicky was a sensitive, skinny white boy and he was only just learning so that strength was hard to call on. Connection gives you a foundation, a real strength.”

Lisa Tumahai

Ngāi Tahu deputy kaiwhakahaere.

Ngāi Tahu deputy kaiwhakahaere Lisa Tumahai has her own personal experience with suicide. Her brother Daniel took his life 16 years ago after moving to Australia.

Speaking to TE KARAKA, she reflects on the difference between 16 years ago and today.

“There is a huge difference. I think much more is being done, but if you ask me if there is more to do, I would say ‘yes’.

“There is always more to do. Whatever health issue you are talking about with Māori, there is always more to do. Statistics would probably tell us we are not doing enough.”

“People say ‘it’s not macho, it’s not Māori to take your own life, it’s not tika.’ Who are we to say it’s not Māori? That’s not what statistics tell us… It’s hard enough he took his own life and that he had these issues, then there was all the talk on top of that. It was made more difficult.”

Lisa Tumahai

Ngāi Tahu deputy kaiwhakahaere

Ngāi Tahu does not directly provide mental health services. It uses sanctioned providers such as Kia Piki te Ora Māori suicide prevention.

However, they endeavour to create awareness using avenues such as Tahu FM bringing in people to talk about these matters openly on air.

When her brother died, Lisa says her parents had to cope with “blaming and murmuring in the wider whānau.”

Daniel James Tauwhare.

“People say ‘it’s not macho, it’s not Māori to take your own life, it’s not tika.’

“Who are we to say it’s not Māori? That’s not what statistics tell us.

“The shame my parents went through. They were grieving. It’s hard enough he took his own life and that he had these issues, then there was all the talk on top of that. It was made more difficult.”

Lisa says she is aware of four Māori/Ngāi Tahu suicides since October last year.

“We have had a number of youth suicides on the West Coast, so I don’t think enough is being done over there, and there is still an element of stigma.

She believes more needs to be done nationally to change the way resources are allocated and the services provided.

“In the South Island especially, we get a raw deal in terms of MOH/DHB resource allocation and Te Rau Matatini. He Waka Tapu in Canterbury does a wonderful job with their Kia Piki te ora suicide prevention service as does Ngā Kete Mātauranga Pounamu in Invercargill who is leading out the implementation of Kimiora – tikanga Māori-based suicide intervention training in Murihiku and Waitaha. But these support services are not getting to our smaller regional communities, they are not funded to and are likely to need stronger supports to meet their own community’s needs.

“On a personal level now, I try to be mindful of the people around me. Life can be so stressful and if I think of the level of suicides within our Ngāi Tahu people, I know we have to be more mindful of each other.

“You might work beside somebody but you never know what is going on with people in their personal lives and at home.

“We need to take these conversations on to the marae and talk about them as hapū and whānau rather than iwi.

“We have to go right down to driving those issues at a hapū and whānau level and be more open about them.”

In order for these conversations to filter through, she believes individual champions, likely to be people with personal experiences in each region, need to drive the discussion on marae.

“I would just encourage our hapū and whānau to engage more in the conversation, particularly if they have been affected. I know people are out there and we need to encourage them to speak and feel supported.”

Meanwhile, with the average of nearly 600 nationally each year, Jane says Nicky’s memory will live on through his family and their courage to speak publicly about mental health. They want people to know how important cultural grounding is for Māori youth.

Jane will remember that spiritual strength through Nicky’s treasured pounamu.

“I got that pounamu taonga for him and it was blessed for spiritual protection. He wore it from the day I gave it to him to the day police cut it off his body when they pulled him out of the river and I will never forget that.”

Where to go for help

The Mental Health Foundation’s free resource and information service (09 623 4812) will refer callers to some of the helplines below.

• Lifeline (open 24/7): 0800 543 354

• Depression Helpline (open 24/7): 0800 111 757

• Healthline (open 24/7): 0800 611 116

• Samaritans (open 24/7): 0800 726 666

• Suicide Crisis Helpline (open 24/7); 0508 828 865 (0508 TAUTOKO). This is a service for people who may be thinking about suicide, or those who are concerned about family or friends.

• Youthline (open 24/7): 0800 376 633. You can also text 234 for free between 8 am and midnight, or email [email protected].

• 0800 WHATSUP children’s helpline: phone 0800 942 8787 between 1 pm and 10 pm on weekdays, and from 3 pm to 10 pm on weekends. Online chat is available from 5 pm to 10 pm every day at www.whatsup.co.nz

• Kidsline (open 24/7): 0800 543 754. This service is for ages 5 to 18. Those who ring between 4 pm and 9 pm on weekdays will speak to a Kidsline buddy. These are specially trained teenaged telephone counsellors.

• Your local Rural Support Trust: 0800 787 254 (0800 RURAL HELP).

• Alcohol Drug Helpline (open 24/7): 0800 787 797. You can also text 8681 for free.

• Alcohol Drug Helpline also have a Māori Line (0800 787 798), as well as a Pasifika line and a youth lin