Connection

Dec 19, 2022

Bronwyn’s whānau at Arowhenua Hui-ā-iwi 2022; from left: Karuna, Te Miringa, Serenity with Te Āwhina in the front, Kahurangi at back, Harikoa and Te Manaaki. All able to kōrero, ranging from age appropriate fluent, to Panekiretanga graduate.

I tipu mai au i te poho o tētahi whānau whāngai, he whānau Pākehā. Ahakoa he Pākehā, he mea nui ki tōku māmā whāngai ngā mātāpono tika pāpori, ā, e mōhio ana ia ki ētahi o ngā aituā, o ngā āhuatanga hē, o ngā āhuatanga kino anō, kua puta ki ngā iwi o Waikato. Nā Bronwyn Thurlow.

I a au e piripoho ana, e kōhungahunga ana, i te manaaki tōku māmā i ētahi o ngā tama nō roto i te whare herehere taiohi o muai Murihiku.

Ka kawea rātau ki te whare karakia; ka kai tahi; ka mutu, ka noho ētahi o rātau ki tōku kāinga i mua i te mutunga o te noho herehere. Tokomaha ngā tama i eke ki te 21 tau i tō mātau taha, ā, i kai keke mātau.

He āhuatanga harikoa katoa ki tēnei tamaiti, te tokomaha o ngā tama Māori i haere mai ki tōku whare ahakoa ka 2 rā te roa, ka 2 tau rānei.

I mutu ērā tikanga i te wā i pāngia tōku māmā e te mate pukupuku, ā, ka hinga ia i te wā e iwa ōku tau.

Ruarua noa ngā āhuatanga reo Māori i ngā kura o aua wā – i akona peahia te waiata ‘Me he manu rere’ anake.

Kāore au i tino whakaaro ki tērā, tae noa ki te wā ka kitea he pānui i te hokomaha i Hornby, ‘kei te hiahia koe kia akona te reo Māori e ngā tamariki?’

1983 te tau i neke mai tōku whānau ki Ōtautahi, ko mātau ko taku hoa tāne, ko āku pēpi tokorua (e 3 tau te pakeke o te mātāmua; e 3 marama te pakeke o te pēpi) ko tāku irāmutu.

Bron’s whānau whāngai – adoptive family, about 1959; in front: father Viv Allott, mother Elnora, née Warnecke, and Bron; behind: siblings Chris, Yvonne, Kenneth and Robin.

I te kimi kura tuarua hou ahau mō tāku irāmutu, nā te mea ko tōna hiahia ko te ako i ngā tikanga pūtaiao, arā, ko te mātai ahupūngao.

Ko te urupare a te kaiako i te kāreti o taua tāone, e kāo. He maha āna take; engari i te wā ka puta te kōrero ‘Ehara au i te kaikiri, engari…‘ ka hōhā haere au. Ngā mihi ki Te Puna Wai o Waipapa ki Ōtautahi nei; kāore he raru i reira.

Kia hoki anō ki taua pānui i kitea i te hokomaha; ‘kei te hiahia koe kia akona te reo Māori e ngā tamariki?’

He kōrero e pā ana ki tētahi kaupapa hou, arā ko Te Kōhanga Reo. Ka tino harikoa te ngākau i ngā kupu – ko taku hiahia, ko te ako i te reo rangatira!

I haere au ki te hui mō te kaupapa.

Ko te kaiwhakahaere o taua hui, ko Kath Stuart nō Rāpaki hei kanohi o te tari Komiti Whiriwhiri Take Māori.

I tīmatahia tō mātau Kōhanga Reo i te marama o Mei i te tau 1983. Te nui hoki o te mahi whai pūtea; i whakatūria he rāwhara, i whakatūria he hui ‘rākau ki runga’; i tunu keke, te mea, te mea. He kōhanga reo rua tō mātau kōhanga i te tīmatanga nā te mea kāore

i taea e mātau te whai kaiako ‘kaha ki te kōrero Māori’.

I hui tahi ngā kōhanga reo katoa o Ōtautahi ki Rehua i te marama o Oketopa 1983. Koirā te wā tuatahi i eke au ki runga i tētahi marae. Ki reira rongo ai ahau i ngā uara nui o te ao Māori.

Ko te mea tuatahi, ko te whakapapa. Ka auē atu au; kāore au i mōhio ki tōku whakapapa; pērā i te tangata kāore ōna waewae; me pēhea hoki e tū?

Nā Terehia Kipa, te kaiako o Te Kōhanga Reo o Rehua ahau i manaaki; nā Riki Ellison anō. Hei aha noa; ahakoa kāore au i mōhio ki tōku whakapapa, ka taea tonuhia te ako i te reo!

I kimi āwhina mātau ngā whānau o te kōhanga reo i hea rānei. I aua rā, arā ētahi hui ako mā ngā whānau i ngā pō; Ngā mihi ki a Alex Simons, ki a Doug Harris, ki a John Stirling anō.

I haere au ki te whare wānanga, ka whāia ētahi pēpa reo i te taha o Lindsay Head.

Proud Aunty Bron (8 years), 1965.

Ina tū ana he wānanga reo i Te Kōhanga Reo, i reira mātau ko āku tamahine.

I te wā i haere āku tamāhine ki te kura, i tautoko au i ngā mahi reo ki ērā kura; ko

Rudolf Steiner, ko te kura tuatahi o Aranui anō.

I haere hoki te whānau ki te kapa haka o Te Kotahitanga.

I te tau 1999 I whai mahi au ki te Whare Whai Mātauraka ki Ōtautahi hei pukenga reo; ka whai tonu i te reo. Ka ako i Te Huanui ki te taha o Hana O’Regan rātau ko Tahu Potiki ko Whai Rohe.

Ka puta te moemoeā o te iwi, arā, ko Kotahi Mano Kāika, Kotahi Mano Wawata. Ka whai akoranga au ki ngā kura reo nā Te Taura Whiri, ki ngā wānanga, ki ngā kura reo ā-iwi, me ngā kura reo ā-kōhanga.

Ki ahau nei, ko te tihi o tērā mahi, ko te wā ka whānau mai ngā mokopuna, arā, ko te reanga tuatoru. Kua kīia, ‘kotahi te reanga e ngaro ai te reo; e toru reanga kia pūāwai anō’.

I puta i te whānau te whakaritenga; kia kōrero Māori anake ki ngā mokopuna. Ka hoki atu au ki te kōhanga reo, hei kaiāwhina.

Ka hui mātau ki te taha o ētahi atu whānau Ngāi Tahu, ki Te Puna Reo o ngā Matariki.

Ko te hua pai, he mahi ā-whānau tērā. Ahakoa te rerekētanga o ngā taumata reo o tēnā tangata, o tēnā tangata, i kitea te whakapaunga kaha o te katoa, ā, ka puta ngā hua.

Tokowhā āku nei tamariki; tokotoru ngā mokopuna. Ko te take e poho kererū ana au, he kōrero Māori te katoa. Mauri tū, mauri ora, kua manawa tītī ngā mokopuna ā muri ake nei. E kore e mutu ngā mihi ki ngā kaiako, ki ngā tuākana, ki ngā kuia, ki ngā koroua, me ngā taniwha reo.

I was adopted out of my whānau, and raised by a Pākehā whānau. I knew all my life that I was Māori and that I was adopted. My parents expected that when I was 21 I would have access to my birth records.

They were mistaken; somewhere between being given me as a three-week-old baby, and the final legal adoption being rubber-stamped, the law determined that adoptive children would have no rights to this information.

My adoptive mother was a social justice advocate, and opened our home to young Māori who had found themselves in the Invercargill borstal. She made sure I knew she didn’t believe those boys would be there if they were Pākehā. So, my earliest childhood was full of Māori teenagers being taken to church, and young men having 21st birthday cakes at our home. Needless to say, those boys spoilt me, and ‘Māoridom’ to me meant guitars, songs (mostly Pākehā) and even saxophones.

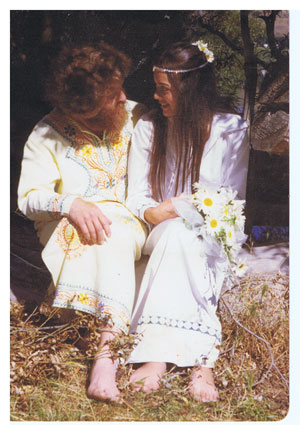

Bronwyn and hippy wedding by Lake Hayes, 1977.

However, my mother became ill and died of cancer when I was nine, and I was deprived of these contacts. I only remember learning one waiata at school in the early 60s, Me he manu rere, and much later I realised some of the words we had been taught were mistakes.

My oldest sister married a Māori, a descendant of Rua Kēnana, and I was so proud to become an aunty at eight years old. Later, when I had married and had my own daughters, it was decided one of my nieces would come and stay with me for a year. So at the start of 1983 I took her to the local college to enrol. She wanted to do Sixth Form physics and was told a bunch of reasons why this was a bad idea: it would be too hard; there weren’t that many Māori girls who made it to Sixth Form; etc etc. It was the phrase ‘I’m not racist but …’ that had me stand up with my three-year-old and my new baby, say rude words and vow I would find a school that would let my niece take physics if she wanted to.

A two-day pack up and we were all off to Christchurch to enrol my niece at Hagley Community College. Because they had adult students I was able to do Sixth Form physics with my niece. We were all staying with close friends initially, and I was looking for places to live, scanning supermarket notice boards for places to rent. That’s when I saw a little poster inviting those interested in having their tamariki learn te reo Māori to attend a planning hui.

It was the first time I had heard about Te Kōhanga Reo. I was totally captured by the idea, I agreed to serve on a komiti, and boom! Our kōhanga doors opened for the first time in late May 1983 at the Hornby Community Centre.

Initially we were a reo-rua bilingual kōhanga because we didn’t have enough speakers to keep te reo going for a whole day, but we did what we could with what we had.

Personally, I took every opportunity to learn at night classes (run by Alex Simon and Doug Harris) and parents’ sessions at the kōhanga (run by John Stirling).

Whānau photo, Jan 2013 – Bron’s tamariki and mokopuna, with partner George, and best friend forever Margie and her three tamariki. This is the close everyday village that raised our collective tamariki.

My first visit to a marae was in October 1983 at Rehua, where I was confronted with the importance of whakapapa – which I didn’t know. I wailed about this, and was adopted on the spot by Terehia Kipa, the kaiako at Te Kōhanga Reo o Rehua, and given all sorts of encouraging words from kaumātua, including Riki Ellison.

I followed my tamariki into their mainstream schooling, contributing where I could to te reo me ōna tikanga, becoming a Māori language teacher of sorts at Rudolf Steiner School, and a bicultural adviser for Early Childhood Education Teacher Training.

Eventually I became a reo Māori lecturer at Te Whare Whai Mātauraka/College of Education, and was mostly teaching simple reo Māori to ECE student teachers. While there I was able to upskill by joining CPIT Te Huanui immersion course, with Hana O’Regan, Tahu Potiki and Whai Rohe as tutors. This course really helped me jump up in te reo ability. Many students find they get to a plateau for a while and discover it’s really hard to get to the next level.

It was in 2001 that I found my whakapapa, and connected with my birth whānau. Meeting my aunty for the first time was one of the most mind-blowing experiences I have had. There were lots of tears and laughter and explanations about how I am related to every second Māori in the world, it felt like. Several whānaunga were with her, and I discovered I had met or even studied beside some of my closest whānau, or had met them through the Kōhanga Reo network.

Bron’s lockdown bubble 2021 –

photo of whānau “formal Friday” with Te Manaaki and Kahurangi.

One of the first things I did to celebrate being Ngāi Tahu was to register with Kotahi Mano Kāika, the Ngāi Tahu reo revitalisation strategy which aspired to have 1000 Ngāi Tahu homes speaking te reo by 2025.

I was able to attend some of the Te Taura Whiri Kura Reo, which was exhausting but so valuable.

The next adventure in learning te reo was when my eldest gave birth to one, and then another mokopuna. The decision was made that these mokopuna would be raised with te reo Māori as their first language.

Baby Bron in 1957, with my late sister Yvonne (14) and a little bit of my brother Chris (7).

So, it was back to Kōhanga Reo, working with the next generation, and using every strategy we could collectively think of to flesh out our reo deficiencies. We were also able to be part of Te Puna Reo o ngā Matariki with the mokopuna; meeting once a week with like-minded reo-speaking mostly Ngāi Tahu whānau, and arranging other reo get-togethers with wider whānau too.

Over the years, my four tamariki have done what they could to learn and teach te reo Māori through our own iwi initiatives, university, wānanga, Te Taura Whiri, and for one, the Te Panekiretanga initiative with the real taniwha of our language. It’s been hard. Exhausting. Expensive. Demanding. As a whānau we have relied on so many others at different times, support from my Māori and Pākehā whānau, support from non-Māori friends, partners, my BFF and her sharing her tamariki, co-workers and colleagues.

And when our six-year-old bilingual mokopuna laments that the greatest loss she has felt with all the Covid-19 restrictions has been the Kura Reo Kāi Tahu at Arowhenua Marae, that’s what has made it all worthwhile.

Mō mātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei.

Bron was a singer in a rock and roll band called Abraham, from 1971/72 – this photo is the band

42 years later, at a reunion performance at the Southland Musician’s Club Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 2014.