Expanding Whānau Horizons

Dec 20, 2020

Since 2019, a series of school holiday wānanga held in Ōtautahi has been supporting a group of rangatahi Māori as they prepare to transition from education to the workforce. Designed for the great-great-mokopuna of Eruera and Amiria Stirling, the wānanga bring together an increasingly disconnected generation of rangatahi. Programme leader Amiria Coe hopes that by removing barriers and creating enablers to success, the wānanga will turn the tide on four generations of missed opportunities. Anna Brankin reports.

Above: Amiria Coe, daughter of Aunty Kiwa.

Mereana Mokikiwa Hutchen (née Stirling – Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Porou, Te Whānau-a-Apanui), or Aunty Kiwa as she is more commonly known, grew up in rural Raukokore on the East Coast of Te Ika a Māui, one of nine children to Eruera and Amiria Stirling (née O’Hara).

Aunty Kiwa’s parents placed great value on learning, educating them in te reo and mātauranga Māori at home and emphasising the importance of their attendance at the local primary school.

“Mum and Dad believed that education was very important, as long as we didn’t lose the Māori. They always said, ‘be mindful that you’re a mixture of both Māori and Pākehā,’” she says. “We were always taught to learn both languages and how to live in both worlds so we wouldn’t feel out of place in either.”

However, the realities of farm life were challenging – the whole whānau were up before dawn every day to milk cows before the children travelled 10 miles to school on horseback. “That’s a long way to go so you had to make sure you caught your horse the night before and tied it up near the house, otherwise you’d be chasing the horse round for hours on end when it came time to go to school,” she says.

After school there were more chores – acres of land to look after, water to be carried up to irrigate crops (provided there had been enough rain to fill the tanks), or tending the vegetable garden the whānau relied on with no nearby shops. With so much work, it is perhaps no surprise that Aunty Kiwa left school after completing Standard 4, with no particular aspirations. “I was too busy milking cows to have any idea of what I might do with my own life,” she says. “It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I thought I would like to go into nursing.”

By the age of 14, Aunty Kiwa had moved to Ōtautahi and secured her first job as a telephone exchange operator. Eventually, she fulfilled her dream of nursing, training at Langford House in Ōtautahi and working as a nurse until she married at the age of 21.

Aunty Kiwa had seven children with her husband Peter Hutchen, including Amiria Coe – named of course after her maternal grandmother. Now a grandmother herself, Amiria came up with the idea of creating a wānanga for the rangatahi in their whānau after observing several were not living up to their full potential.

“The idea came from looking at my own grandchildren, and my great-nieces and nephews. I’ve got five sisters, and we all had our children together,” Amiria says. “When our children hit high school, they struggled to stay in school beyond Year 11. And of course we had all left school when we were 14 or 15, so we didn’t have anything better to pass on to our children.”

Above: Aunty Kiwa, aka Mereana Mokikiwa Hutchen.

Amiria says she and her sisters simply didn’t have the skills or experience to help their children navigate high school and prepare them for the transition to higher education or employment – a cycle that she realised would repeat itself indefinitely unless she found

a way to intervene.

“What I saw coming through was our grandchildren starting to hit that age, and they didn’t have a clue what they wanted to do,” she says. “I noticed that some of our kids were slipping through the gaps. They were finishing school, taking a gap year and then never going back to education. Or they’d go into some course or other that achieved nothing except accumulating debt.”

For Amiria, the first step to breaking the cycle was to reflect on her own journey and identify why she had turned her back on education at such a young age. Although her parents had always prioritised education for their children, Amiria believes they simply didn’t realise the complexities and shortcomings of the education system. “I think their idea was that they would parent us at home, and that we would be educated at school,” she says. “Mum would always tell us to stay in school, to get School Cert and UE, but when we asked her, ‘what for?’ she didn’t actually have an answer other than that it was what you were supposed to do.”

Aunty Kiwa was involved in the creation of Pūao-te-ata-tū, a landmark report that highlighted institutional racism towards Māori and emphasised the importance of whānau, hapū and iwi … Her experiences made her a source of invaluable support and encouragement when her daughters created Te Whare Hauora – Ōtautahi Māori Women’s Refuge.

Somewhere along the way it seems Aunty Kiwa picked up the misconception that she and her children needed to be realistic about their own potential. Her decision to go into nursing was a perfect example: despite being interested in medicine, it never occurred to her to become a doctor. “I never even thought about it,” she said. “I liked the idea of being a nurse, but the idea of being a doctor – that seemed too hard.”

Although Aunty Kiwa’s personal aspirations may have been lowered, it was her aroha and community spirit that fuelled the important work she has become known for throughout Aotearoa. In the 1980s, Aunty Kiwa and Peter became the first Ōtautahi home to operate under Mātua Whāngai, a programme that sought to help Māori children in care by placing them within traditional whanaungatanga relationships. Over the years they welcomed more than a hundred tamariki into their home.

Above: Stirling whānau wānanga at Ara Institute of Canterbury.

Aunty Kiwa was also involved in the creation of Pūao-te-ata-tū, a landmark report that highlighted institutional racism towards Māori and emphasised the importance of whānau, hapū and iwi. She has been the kuia for the Christchurch Women’s Prison, providing support and guidance to inmates and contributing to cultural developments within the Department of Corrections. Her experiences made her a source of invaluable support and encouragement when her daughters created Te Whare Hauora – Ōtautahi Māori Women’s Refuge.

In 2008, Aunty Kiwa accepted a Queen’s Service Medal (QSM) for services to Māori, women and the community. She had actually first been awarded the honour in 1992, but she turned it down because her brother, Dr Ropata Wahawaha Stirling, was awarded his QSM the same year and she didn’t want to detract from his success.

While her children inherited her passion for whānau, hapū and iwi, that humble tendency also found its way into Aunty Kiwa’s parenting. “As a parent, mum’s encouragement into certain types of work was very narrow,” Amiria says. “I remember coming home once and suggesting that I might want to be a lawyer when I grew up, and she said, ‘ah no, you will be the secretary for the lawyer.’”

When Amiria considered these anecdotes side-by-side, she realised how easily an internalised misconception about one’s own limitations could be passed down through generations – even in the most loving and supportive whānau. And unfortunately it is a misconception that is perpetuated within the New Zealand school system, which has a long history of delivering poor outcomes for Māori.

“I hated school. I was probably a horrible little shit with a big attitude, but I do think we got treated badly,” Amiria says. “I very clearly remember one teacher who sat me down and said, ‘Amiria, if you only knew, you have great things in you.’ The reason I remember it so clearly is that she was the only teacher who ever took the time to ask what we wanted to do or help us figure out what we were good at.”

Unfortunately, one supportive teacher was not enough to turn the tide and Amiria’s overwhelming memory of school is being grouped together with the other Māori kids and streamed out of the subjects that would have led to better opportunities. Discouraged and disinterested, Amiria and her sisters all left school around the age of 14.

“I know that if we’d been interested and motivated, we would have had a whole different outlook,” Amiria says. “I’m not stupid and neither were my mates and my cousins, but our teachers didn’t seem to want to deal with us. I don’t think we got a fair shake, and now we’re struggling to help our mokos.”

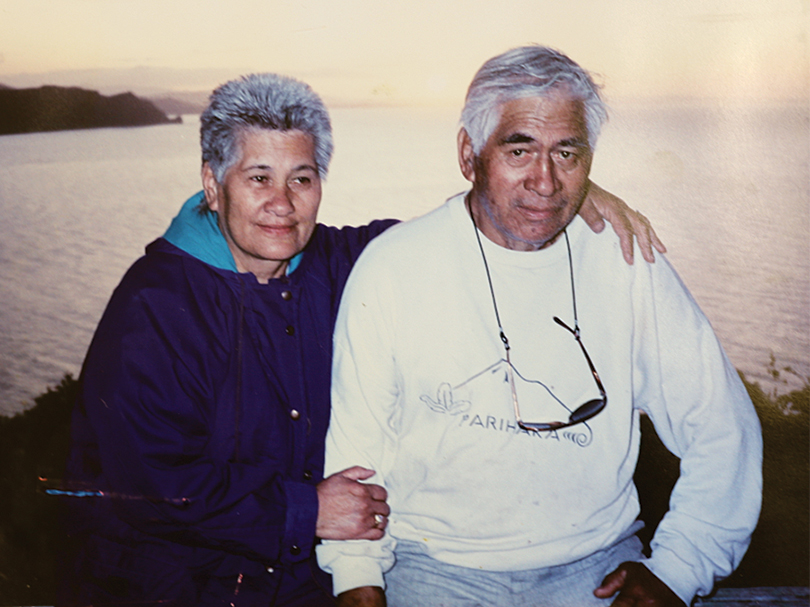

Above: Kiwa with her brother Ropata Wahawaha (Waha) Stirling.

Amiria was married with two children by the age of 17, and for the next 10 years she worked in a series of low-paid, unskilled jobs with no objective other than to earn enough money to pay the bills and provide for her children.

When she was 27, Amiria was given the chance to work as a facilitator for the YMCA Support Training and Enterprise Programme (STEP), helping young people to overcome barriers to education and employment. “I freaked out in the interview because of all the personal questions, but afterwards he said that my life experience made me perfect for the job,” she recalls. “He said, ‘everything that young people face, you’ve been through it.’ That was completely new to me because I’d always felt like my life experience was useless without any qualifications.”

In 1990, Amiria’s life changed again when her boss encouraged her to attend a three-day course on the Treaty of Waitangi. “Before that my attitude towards the Treaty was like, ‘what’s it got to do with me if my ancestors sold all their land for blankets?’” she says. “At this course we learned about the whole history of the Treaty and the process of colonisation and it changed my thinking forever. It put me in a position to make a commitment to my people, to my family and to the generations coming.”

This commitment has supported Amiria through her role at the YMCA and later in her work with children who have experienced violence, and now it is what has driven her to create a wānanga series for the next generation of the Stirling whānau. Her first step was to reach out to her cousin Tarlin’s husband, Piripi Prendergast.

“I don’t want our mokos to be left behind, and I worried that our lack of experience was preventing us from being able to support them,” Amiria says. “So I hauled Piripi in. I got in his ear and said ‘this is my plan, and I’m sending them to you.’”

As a former high school teacher with extensive experience in bilingual programmes and kura kaupapa, Piripi has proven his ability to get through to rangatahi Māori. These days Piripi is working for Tokona Te Raki as a convenor, supporting the vision of equity for Māori in education, employment and income. What’s more, his whānau connection made him the perfect person to bring Amiria’s vision to life.

“One part of the pathway to success is trying to open up opportunities for these young ones,” says Piripi. “The second part is challenging the schools and the system to change their delivery, and the third part is actually working with our rangatahi to open doors in their own minds, to raise their aspirations and say ‘you can actually do this.’”

Above: Great-moko Matariki interviewing Kiwa about her life.

Nearly two years in, and Amiria couldn’t be happier with how the wānanga are going. “For the first one, I was messaging them all on Facebook and going around to their houses to pull them out of their caves,” she says. “Now I have them saying to me, ‘when’s the next one?’ because they don’t want to be left out.”

Of course, these wānanga wouldn’t be complete without the support of their kuia Aunty Kiwa, who is delighted to see her great-mokopuna coming together for this kaupapa. “What Piripi is doing with those kids is just great. It’s so important that whānau are connected together,” she says. “Isolation and losing the language has had an impact, and what I’m seeing today is that there’s no more talking.”

During these wānanga, the rangatahi have tackled the beast head on by researching and writing a report on the challenges faced by these four generations of the Stirling whānau, conducting interviews with 10 descendants. “We all have our own stories about our journey from leaving school to getting our first real job,” the report reads. “For some we knew what we wanted to do, school had prepared us well and the transition was easy. Others left school ill-prepared and what followed were some years of wandering, searching for the right career path. For others, the wandering hasn’t really stopped.”

The report concludes that the challenges of transitioning to work are getting more complex with each generation, and that rangatahi are not getting the support they need from school career advisers.

Although the experience of the Stirling whānau is of course unique to them, these patterns are repeated in many whānau throughout Aotearoa. These rangatahi hope to learn from the experiences of older generations and weave a new pattern for themselves and those to come, allowing them to reach for a future they might only have dreamed of before.