Facing up to climate change

Oct 15, 2012

How can small Ngāi Tahu communities manage something as ominous as climate change? Arowhenua people are looking for their answers to the present and future situation in what has happened in the past. Kaituhituhi Greg Meylan talks to Darren Ngaru King and whānau from Arowhenua Pā about research centring on Arowhenua and how it can benefit the local community.

For centuries the people of Arowhenua in South Canterbury have witnessed the heavens open, the rivers bursting their banks and floodwaters swamp the low-lying land. They have also endured droughts, snowfall and storms.

The Ngāti Huirapa community from Arowhenua Pā is working on a collaborative project with research scientists from the Māori Environmental Research and National Climate Centres at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

Collectively they are looking at what can be learned from Māori ways of dealing with past climate risks, particularly when extreme weather events are expected to become much fiercer and more common in some regions. They are also assessing how the home people from Arowhenua Pā are likely to be impacted by climate change this century, evaluating their risk to climate change, and identifying actions to strengthen their resilience.

Marae chairperson John Henry says the discussions helped them to frame the issue of climate change. “It opened our eyes up to what could happen and how to prepare ourselves a little bit better.”

Karl Russell, a member of the Arowhenua Mātaitai Rōpū, says the process was extremely useful and there now needed to be discussions within the whānau about some of the issues raised, particularly the potential loss of coastal land due to rising sea levels.

“For our people I think it was very beneficial. It made us aware of the potential loss of land. We now have to think what to do with that land. These are very hard decisions.”

“For our people I think it was very beneficial. It made us aware of the potential loss of land. We now have to think what to do with that land. These are very hard decisions.”

Environmental scientist Darren King (Ngāti Raukawa) says NIWA and Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua Society Incorporated worked closely together on the project.

The aim was to make some sense of how the home people from Arowhenua Pā are likely to be impacted by climate change this century, and assess their risk to climate change and identify actions to strengthen their capacities to deal with potential impacts.

He says at its heart, the research aims to answer some basic questions:

“How will climate change impact me, my whānau, my hapū?

Why should I think about climate change and what are some of the things that can be done to ensure our community is best prepared?” says King.

To help answer these questions, a series of group and individual meetings were held with the Arowhenua community that resulted in many hours of transcribed thoughts on everything from mahinga kai to rapid changes in the community, from flooding to the challenges of meaningful engagement with local government.

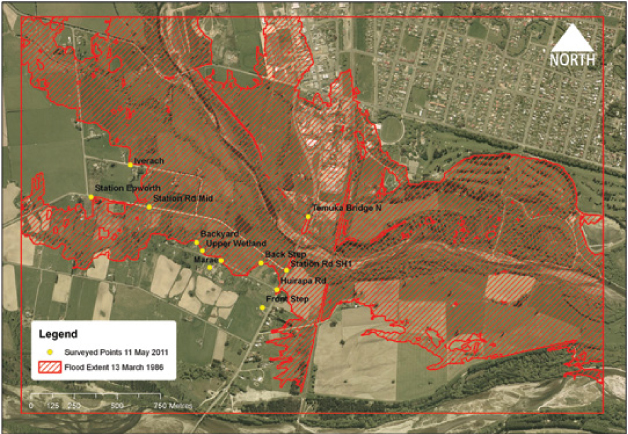

Climate change-induced peak flood levels and extents were also modelled for the Temuka River for 2040 and 2090; as well as extreme storm tide levels along the Temuka coast that include best estimates of sea level rise for 2040 and 2090. These information sources were then used to consider future risks and adaptation options.

King says one of the most important things to come out of the project is the community recognition that successful climate adaptation planning must deal with the linked issues of sustainable development and natural hazards management.

“Being prepared to deal with extremes in weather and climate, from flooding to drought, is a very effective way of strengthening a community’s ability to cope. This includes everything from having disaster plans, to insurance for the most at risk homes, to a supply of spare batteries.”

But King says it is also important to acknowledge that none of the challenges of climate change are entirely new. “Māori have always dealt with and faced climate related stresses and sensitivities and dealt with them in a whole lot of ways,” he says.

As one community member told the project team: “The people who put us here made a good choice – it’s dry. And like most Māori they picked a good spot to live, in rain, hail or shine.” Another said: “An old kōrero that I’ve been told is when the very first settlers came in here and were living in this area, they were told don’t build here and here because it floods … Our people knew where the safe ground was.”

The research findings showed Māori values and approaches such as tikanga and kawa that are actioned through whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, tautakotanga and kotahitanga are the real sources of community endurance and resilience.

During one of the meetings, one of the community members said: “I think we cope with anything that comes along because we’ve had to; we’re brought up like that … That comes from our parents who were bought up with it before us, they showed us how to go about and what to keep an eye out for and what hazards to look for … we’re still doing it.”

The project showed the community is vulnerable to changing climate conditions, with some members more at risk than others.

This vulnerability comes from multiple sources including whānau whose houses are either in low-lying areas or threatened by coastal erosion as well as things like: land-use change and the destruction of mahinga kai, young people being drawn away from the pā to the cities for jobs and education, a reliance on modern technology and decreases in Māori-owned land holdings. All these changes and challenges affect the way whānau deal with climatic risks.

Reducing some of these influences requires meaningful engagement with local government. This is where King hopes the capturing of community whakaaro and experience will help. “It is valuable to have people’s voices captured. To communicate to external parties what it is like for Māori.”

Karl Russell adds that “We know what is going on with our awa. We have hundreds of years of knowledge and history.”

King hopes the work done by Ngāti Huirapa will also assist Māori communities in other places to tackle the challenges of climate change by providing an example of how to work through the complexity of the issue.

He says it is also important for other iwi/hapū/whānau to know that there is already a lot of information about expected impacts and risks already out there. Communities can combine this with an analysis of their own strengths and vulnerability to determine next actions.

NIWA will soon complete similar studies working alongside Ngāti Whanaunga at Manaia in the Waikato, and Te Tao Māui at Mitimiti in the northern Hokianga.

Jointly these projects will help to make grounded assessments of climate change risk facing Māori communities across the motu. This understanding will be critical for identifying options for action.

Key aspects of the research will be covered at the Third Māori Climate Forum scheduled for early 2013.

The final report produced for Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua is available through NIWA’s Climate and Māori Society project web-pages:

www.niwa.co.nz/climate/information-and-resources/climate-and-maori-society.

Options identified by the community

- Reducing risks from flooding and sea level rise

- Raise the flood prone parts of main roads into Arowhenua Pā.

- Elevate low-lying homes and consider restricting new development on coastal land threatened by rising sea levels.

- Plan infrastructure for what the locality will face over the next one to two generations, not just what it needs today.

- Remove debris and build-up along the river.

- Protect and enhance ability of wetlands and watersheds to store water, and thereby reduce some of the potential impacts and risks caused through extreme flood flows.

- Enhancing community resilience to climate change risks

- Raise hapū awareness of climate change.

- Promote and reaffirm old-ways of collective action, environmental knowledge and natural resource management.

- Create a hazard emergency response plan and participate in local governance and institutions that encourage disaster prevention and response.

- Engage with regional partners and other relevant organisations to collaborate on climate change-focused initiatives and programmes to prepare for climate impacts.

- Consider climate change adaptation in all hapū/iwi-management planning efforts.