Freshwater – rangatiratanga versus ownership

Jun 29, 2021

Nā Ben Thomas

Above: Lake Māhinapua.

When Wiremu Potiki stood before the Smith-Nairn Royal Commission in 1880 he made it clear he had claimed Te Aunui waterfall twice when accompanying Walter Mantell in his negotiations with the Crown for Murihiku in 1851.

‘Ka kōrerotia anō e ahau tētahi atu rāhui e hiahiatia ana e ahau

ko Te Aunui he rere ki Mataura …

… E rua aku tononga kia rāhuitia a Aunui

I also asked for another rāhui to be placed on Te Aunui, a waterfall at Mataura, I asked twice that Te Aunui be reserved …

He had good reason for this claim. the mataura river and Te Aunui waterfalls were sectioned off among the hapū of Murihiku as it was a prime place to take the kanakana. Herries Beattie wrote,

[o]nly certain hapū (families) had the right to fish there, and each family had a strictly defined pā (fishing spot), the right of which had been handed down from their ancestors.

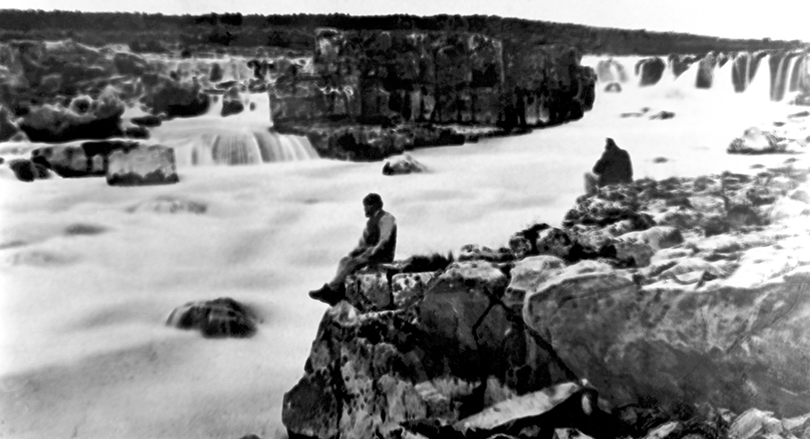

There’s an old black and white photograph of Te Aunui (Mataura falls) that gives a sense of what has been lost. Showing a man, legs dangling off the rocks, over the roaring spray of the river underneath the colossal waterfall, the home of plentiful kanakana and tuna, it was taken before the area was blasted with explosives to make way for a pulp and paper mill and an abattoir in the late 19th century.

The face of the river changed forever.

Above: Te Aunui (Mataura Falls) in the 19th century.

Although the kanakana have survived against the odds, the river remains degraded. Environment Southland says this classification is based on E.coli and dissolved inorganic nitrogen levels in the water.

The photograph of its former glory is part of the evidence that Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and 15 traditional tribal leaders will present in support of their application to have Ngāi Tahu rangatiratanga over wai māori (freshwater) in the takiwā recognised by the High Court.

A statement of claim in the name of traditional leaders, and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu as the representative, was delivered to the High Court at Christchurch and served on the Crown in November last year.

“We are asking the courts to recognise the rangatiratanga that Ngāi Tahu has, and has had since time immemorial, over the wai māori of the takiwā,” says Dr Te Maire Tau, co-chair of Ngāi Tahu freshwater group Te Kura Taka Pini, and who is also representing Ngāi Tūāhuriri as Upoko in the application. “And following that, a declaration that the Crown should recognise and provide for Ngāi Tahu rangatiratanga by working with us to design a new system for freshwater management.”

He says Ngāi Tahu has been forced to take action by the Crown’s continuing failures to address freshwater issues and, crucially, not including iwi in solutions as partners.

“We want to stop the deterioration of our waterways. The most overallocated waterways in the country are in the Ngāi Tahu takiwā,” says Kaiwhakahaere and Te Kura Taka Pini co-chair Lisa Tumahai. “Many of our streams and rivers are in a shocking state, with severe pollution in Canterbury, with Southland and Otago not far behind. This is the result of consistent Crown failures, across many governments, to protect wai māori.”

Rangatiratanga is not the same as ownership, Lisa Tumahai says.

“It includes rights, but also responsibilities and obligations. So our understanding of rangatiratanga incorporates the right to make, regulate, alter and enforce decisions about how wai māori is allocated, used, and managed. It also encompasses the responsibility to see that this is done in a way that puts the environment first, ensures the wellbeing of communities and allows for economic development.”

“Our application comes from our particular circumstances,” Te Maire Tau says. “It comes from the history and practice of Ngāi Tahu.”

Above: Waimakariri River.

Ngāi Tahu rangatiratanga is recognised and guaranteed by the Treaty. The Crown again recognised that Ngāi Tahu is tangata whenua of, and holds rangatiratanga within, the takiwā of Ngāi Tahu whānui in the legislation, giving effect to its Treaty settlement in 1998.

However, Ngāi Tahu rangatiratanga is not derived from Parliament or the Treaty. Ngāi Tahu rangatiratanga existed before Parliament, and before the Treaty.

Prior to 1840, Ngāi Tahu exercised fully the rights, responsibilities and obligations of rangatiratanga over wai māori throughout its takiwā according to tikaka.

The statement of claim describes representative water bodies in the areas of each of the named tribal leaders. They are “representative” because the application is in relation to Ngāi Tahu rangatiratanga in general, not any specific stream or lake, but together they paint a detailed picture of how Ngāi Tahu ensured the responsible management of natural resources in Te Waipounamu.

It also describes how rangatiratanga was established over Te Waihora. The water levels of Te Waihora were regulated by digging trenches and drains and by opening the lake to the sea. Mantell was aware of Ngāi Tahu authority and tikanga over the lake when he visited in 1848, writing,

Waihora is – continually discussed – the existence of legal right inconveniences.

Mantell knew tribal tikanga was the equivalent to legal rights which he saw as an “inconvenience” to the Crown. Those tikanga or what Mantell calls “legal rights” were to be protected under the Treaty of Waitangi as it represented their rangatiratanga – their authority.

Nearly 20 years after the 1848 Canterbury Purchase a good part of Te Waihora had been drained and Pākehā farmers were grazing their stock on the new pasture. Ngāi Tahu held their position telling local government,

… kāore hoki tērā moana i riro i roto i te mahika a te Kepa rāua ko Matara, kai a mātou anō kai kā tākata Māori.

… that lake was not ceded in the Deed made with Mr Kemp and Mr Mantell; it is still ours, the Māoris.

Ngāi Tahu were also aware of the economic stealth that was in play wherein the Crown had managed to drain their lake and convert it into pasture for the Pākehā economy. Our people wrote: “It is being drained off by the Government, so as to be a source of emolument for them – kai te pakarutia tonutia e te Kāwanataka hei utu moni māna.”

This is an old story of colonisation. ‘Taonga’ such as wai-māori were converted into a western form of capital (pasture) which generated revenue for the Pākehā community. Māori were reduced to a labour pool for the white New Zealand economy. In other words Māori became another form of capital in the way cheap labour and our rights to water were marginalised to reserves and fishing easements. This was the Crown’s way to manage the “existence of legal right inconveniences”.

Above: Ōtira River.

Ngāi Tahu has continued to exercise rangatiratanga over wai māori to the extent possible given limitations created by the Crown through legislation such as the Resource Management Act. Te Maire Tau believes the tikanga and rangatiratanga are self-evident. “When Iwikau charged a French whaling ship for water in 1842, he did so because he was the rangatira and that was an act of rangatiratanga”.

That rangatiratanga was assured in the Treaty of Waitangi that he signed two years earlier and reconfirmed in the 1998 Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act that states the Crown,

ka whakaae te Karauna ko Ngāi Tahu whānui anō te tāngata whenua hei pupuri i te rangatiratanga o roto i ōna takiwā.

… in fulfilment of its Treaty obligations, the Crown recognises Ngāi Tahu as the tāngata whenua of, and as holding rangatiratanga within, the takiwā of Ngāi Tahu whānui.

Separately from the court action over freshwater generally, Ngāi Tahu has also been involved in talks with the Department of Internal Affairs about the possible co-design of a new public delivery entity for “three waters” (drinking, storm and wastewater) in the takiwā.

The Ngāi Tahu goal, agreed by tribal leaders, is a water entity within the Ngāi Tahu takiwā that gives effect to rangatiratanga, allows for local solutions, and ensures all communities have equitable access to safe and resilient “three waters” services.

These discussions were wrongly portrayed last month by the Opposition National Party as a plan to give ownership of water infrastructure to Ngāi Tahu, rather than to a new (proposed) independent entity. However, those false allegations provided a good opportunity to openly discuss the benefits that partnership could bring iwi, councils and the community.

“Co-governance with the tribe is actually an effective safeguard against any attempts by future governments to privatise the water infrastructure assets paid for by ratepayers over the years,” says Lisa Tumahai.

“The information about ownership wasn’t true, but it was a reminder of the challenges we have faced, where sometimes people prefer to use Ngāi Tahu as a political football rather than engage with our aspirations which ultimately benefit everyone by instilling environment-first values,” she says.

And it is a message that is becoming more widely known. When the statement of claim seeking recognition of rangatiratanga was filed last November, the respected ecologist Mike Joy told RNZ: “If Māori had more involvement and control over freshwater they would handle it completely differently and make a real positive move in the right direction.”

Lisa Tumahai agrees.

“Ngāi Tahu has centuries of connection to the whenua and resources of Te Waipounamu, and we benefit from the immense knowledge and awareness and wisdom that such a connection sustains. We are forever connected to these lands. It is our only place to stand. With this comes immense responsibility and a genuine concern for the well-being of our takiwā and those it sustains.”