Kai An excuse to Share

Jul 8, 2013

Hāngī are about celebration, tikanga and whanaungatanga. In these modern times, how you make a hāngī can range from the traditional underground oven to using old steel drums heated with gas. There are even hāngī made in recycled beer kegs. But whatever new methods are used, the true taste of hāngī comes from the earth. Kaituhituhi Adrienne Rewi talks with Karl Russell at Arowhenua Marae, as he prepares an old-style hāngī for his birthday celebrations.

Photographs Adrienne Rewi

Karl Russell reckons he was about four-and-a-half when he made his first hāngī. It was a disaster.

“Me and my cousins Kenny and Gary Waaka pinched a chook, a leg of mutton and a few spuds. Although Kenny and Gary were only a year or so older than me, we’d all seen hāngī being made, growing up on the pā; and we’d all helped when we were allowed.

“When it came to making our own that day, we did everything right, except that we used a piece of old waterproof canvas instead of sacks and we pinched a few tea towels for covering it over. When we opened it three hours later, the steam hadn’t been able to get through the waterproof canvas and everything was burnt to a cinder,” he says with a laugh.

Sampson Karst records the hāngī process.

Karl (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa/Ngāti Ruahikihiki; Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha), is 57 now and to mark his latest birthday, he is making a hāngī the old way.

“We grew up making hāngī – although we called them umu – and of course the umu or hāngī is not unique to Māori… Even the Welsh, some Arabic countries and parts of India and Chile had their own version of underground cooking.

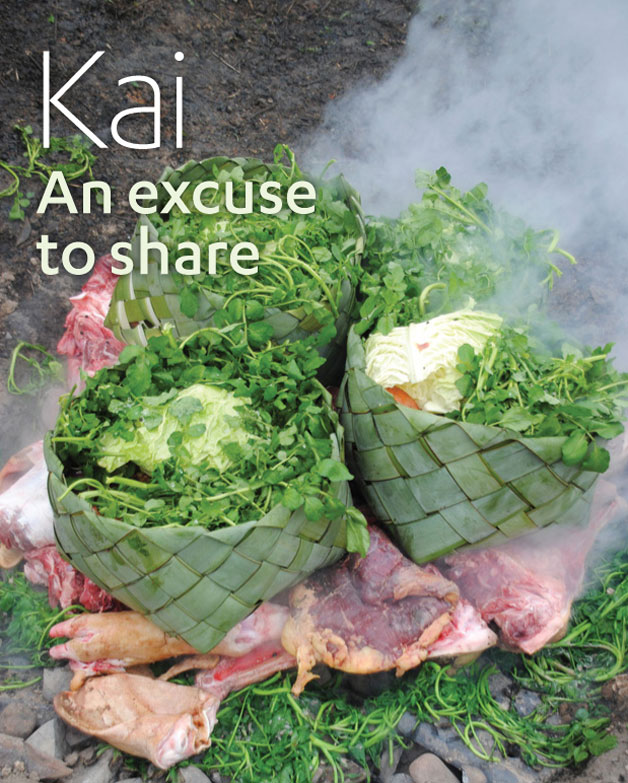

Many generations later, the concept hasn’t changed, but much of the equipment has, and now there are health and safety regulations to abide by. That’s changed the taste of things. Karl wanted to make a hāngī using old-style rourou (woven flax baskets) and harakeke mats, throwing the meat straight onto the rocks, instead of using the wire baskets commonly used now. The natural materials and the hot rocks imbue the food with subtle flavours you don’t get in modern hāngī.

Karl says he appreciates the need for guidelines around hāngī to avoid health issues, but says he can’t remember a case of his old-style hāngī ever making anyone sick.

“We knew how to cook clean in a rough environment – we’ve been doing it for centuries,” he says.

Rab Ngatai lays kindling

Mahinga kai and the kai traditions of his tīpuna are a passion for Karl. He’s followed in the footsteps of his father, George Te Kite Russell, as the Arowhenua Marae cook, and he’s dedicated to the revival of the old ways. He’s encouraging young men back into the kāuta (cookhouse), and he’s working on mahinga kai projects including workshops and developing a traditional kai recipe book.

It seemed a logical step to celebrate his birthday with an old-style hangi.

“Hāngī encapsulate the whole idea of bringing whānau together to celebrate, and I remember those old hāngī being much more flavoursome. That’s what I wanted today. It’s the first time I’ve made a hāngī this way since I was a teenager, 40 years ago,” he says.

Karl’s Arowhenua living room is warm and the freshly woven rourou or kona (woven baskets) and whāriki (mats) are lined up under the window waiting to go into the hāngī. It’s pouring with rain outside, but that’s not enough to deter Karl.

“I’ve got my best hāngī bros on the job with me. They’re all experts and we’re used to working in any weather,” he says, buttoning up his weather-proof jacket.

“The bros are gun hāngī-makers and we have a well-practised routine.”

Taiaroa Benson looks on while Rab Ngatai and Karl Russell stoke the fire.

Out in the wet paddock, between the marae and Karl’s house, his younger brother, Riki Paora-Russell (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa/Ngāti Ruahikihiki; Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha), who is the eleventh of 13 children, Rab Ngatai (Ngāi Te Rangi, Takupapa, Ngāti Hine) and marae caretaker Taiaroa Benson (Ngāi Tahu – Kāti Huirapa), have already dug the fire pit – two-feet deep at most – and they’re carrying armfuls of wood to the pit edge.

There’s a system to laying the fire – newspaper first these days, although in the old days the fire was started by rubbing sticks together then kindling, smaller logs, all the way up to the large, hardwood beams that form supports across the top of the pit. Then the river stones go on.

Karl says he prefers lava, or volcanic stones, which he usually finds washed up on the beach. But time and weather were against him this time.

“Lava stones don’t split in the extreme heat like most river stones, but these will be good. Rab’s whānau have already used them for an umu and they should do nicely for our small hāngī.”

Karl isn’t sure how many will attend his evening birthday celebration but he’s catering for 50.

Layering watercress between the hāngī vegetables.

“Hāngī catering is all about guesswork. But if you know your whānau and your whakapapa, you have the tools for making a reasonably accurate guess. If you’re catering for a tangi for someone of high standing for instance, you might expect around a thousand manuhiri to arrive; but perhaps only 300 would attend for someone lesser-known. I learnt how to bulk cook on the marae. It’s all about experience,” he says, as he lays the last stones.

Once the fire is roaring, it is left to burn down for two to three hours. While that’s happening, the crew seeks shelter from the rain in Karl’s garage, where they get stuck into preparing the kai for the hāngī.

Whānau have arrived to help. There’s Karl’s daughter Kristal Russell and her daughter, Indya Day; and Karl’s niece, Leisa Aumua (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Hateatea, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha) and her two children, Hema Aumua-Carrick (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Hateatea, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha) and Fualili Kihere Aumua-Jahnke (Ngāi Tahu – Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Hateatea, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha, Ngāti Porou, Ngāpuhi, Tainui).

Everyone pitches in to wash the rīwai and chop the kamokamo, kumara, pumpkin, carrots and corn. The watercress is submerged in water to keep it wet, and fresh cabbages from Karl’s garden are chopped.

Taiaroa and Karl butcher the pigs’ heads and pork, mutton, beef and chicken are loaded onto the tray of Karl’s truck, along with the harakeke rourou, containing all the vegetables. Each basket has been lined with watercress, with added cabbage, to stop the vegetables burning.

Hāngī vegetables in the harakeke rourou.

From there, it’s taken out to the hāngī pit. With the river stones at a white-hot temperature, the embers are removed from the pit to prevent the food getting too smoky during cooking. With the white-hot stones back in place, Karl whips them with a wet sack to remove dust and dirt before he lays down the watercress.

Clouds of steam rise and the men move quickly through the process of laying the meat on top of the watercress before stacking on the vegetable-filled rourou. Karl had intended adding kaimoana cooked in pōhā (kelp bags) but the seas were too rough for him to gather the kelp needed for making the bags.

“We lay down the meat first, then the vegetables, and then, if you have it, the kaimoana. The foods that take longest to cook are always at the bottom,” he says.

Everything is hosed down then – even in wet weather to create the steam required for cooking. Next, the baskets are covered with the woven harakeke mats (now commonly replaced by layers of wet sacks). Earth is mounded on top until all trace of steam has vanished – a sure sign it’s trapped inside the mound, where, over the next three to four hours, it will cook the kai to perfection.

Brother and sister Hema Aumua-Carrick and Fualili Kihere Aumua-Jahnke scrub riwai.

The men stand around the hāngī mound leaning on their shovels. It’s time for a beer and a yarn with whānau and that, says Karl, is what hāngī is all about.

“It’s all about friends and whānau coming together to enjoy good kai. It’s a chance to talk about some of the hāngī and some of the whānau who have gone before.

“There’s always a lot of kōrero when you’re doing a hāngī… yes, it’s my birthday, but really it’s just an excuse for sharing good kai and being with whānau.”

Karl is adamant though that it’s equally about passing on the tikanga.

“Take young Hema for instance – he’s done a few hāngī now and he knows the ropes. It’s vital that we pass on this knowledge on to our young people if we want it to survive. Its important to our whakapapa. Mahinga kai is at the heart of who we are as an iwi.”