Mā te wahine, mā te whenua- ka ora ai te tangata

Dec 19, 2022

Jaleesa Panirau and Kelly Barry.

Cousins Kelly Barry and Jaleesa Panirau stand in the shadow of their ancestral maunga, Te Ūpoko o Tahumatā, eyes shielded against brilliant sunlight as they survey the māra kai taking shape before them. Alongside the awa, they walk among recently planted fruit trees and stoop to observe the neat rows of organic seedlings springing up.

It is real, tangible growth that reflects an internal movement stirring from within the Wairewa Rūnanga right now. These two young wāhine have found themselves unexpectedly paired at the helm – and are set to get life blood pumping through the marae, kai in the ground and on tables. Kaituhi Arielle Kauaeroa heads out to Wairewa to capture what feels like a new chapter in history for this branch of Ngāti Irakehu.

Frequent, raucous laughter rolls through the air; that’s how they do what needs to be done, Jaleesa explains. “If things start to feel a bit much, we just have to laugh – and often.”

The pair grew up together playing on the ātea of this marae and have recently stepped into leadership positions within the rūnanga. Sometimes it can be a ‘bit much’, balancing work, personal lives, and the demands of the rūnanga, which essentially boils down to the demands of the whānau. As a 29-year-old, Jaleesa (Jay) became the youngest chairperson for Wairewa Rūnanga last year and, just shy of a decade older, Kelly was appointed general manager in May.

Both roles include big highs, a lot of middle ground grind and a fair share of lows for the two wāhine who are only just finding their individual strides in the mahi.

“They’re both strong leaders in their own right and aren’t afraid to challenge us older ones – which could be detrimental for some, but so far it’s tended to be opinions that we need to hear looking towards the future. It’s been great watching them grow; they move so quickly at times they’ve had to taihoa a bit and learn to listen to others. It’s all part of it, and they’ve got the fundamental things in place.”

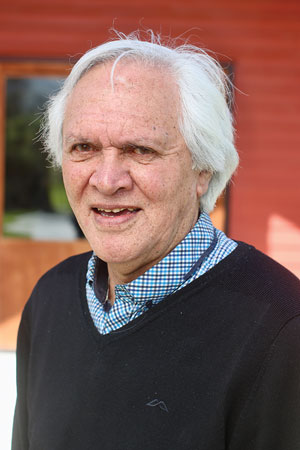

Wairewa kaumātua Theo Bunker.

“The main challenge for me is time,” Jay says. “The time this mahi requires and what that means in terms of prioritising life to do the job well. I wouldn’t say I’m always getting it right, either. I’m not the perfect person for this job at all, but I was the person who stepped up when it came time – and I know whānau generally support me ‘cause it was them who voted me in.”

As an occasionally fearsome and fiery Aries, there have been times when the pressure has peaked, she admits. Fortunately, mahi full-time in the Whakapapa Unit at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu means she has an understanding employer when it comes to balancing work and the enormous commitment chairing a rūnanga takes.

Theo Bunker.

For context, while being interviewed and photographed for this story, her phone received 32 missed calls and text messages; 28 of those were rūnanga related.

Used to being carefree and “a bit of a tipi haere”, Jay has experienced a steep growth curve since being in the role. With an increase in responsibilities she has felt necessarily more grounded – putting her in good stead to weather a bit of personal sacrifice for the job.

“Wairewa Rūnanga are our people and our whānau you know, and I want to see them flourish and thrive; I don’t mind giving a few of my prime years to support that.”

And a few more years is all Jay is promising. She has her sights set on studying a master’s in business administration and can’t imagine doing both at the same time.

“These roles cover a range of different kaupapa and require a lot of stamina; it can feel endless, so it’s good we’re about doing things intergenerationally! Kelly and I will always be here contributing to our people and our whenua, but at some point, we’ll need to step back too.

“I’ve observed succession planning as a tribe has been a challenging task and that’s why we’re focusing our energy out here on Wairewa and Ngāti Irakehu. We feel we can get more done starting with home first, with our own whānau, by growing and nurturing the younger ones to find their passion and confidence to step into these roles.”

Kelly agrees. After her own stint as rūnanga chair in 2019, she saw the biggest barrier for whānau connecting with their marae, rūnanga and the many kaupapa that surround it was a lack of capacity.

“Helping whānau to build that capacity in their own whare and selves first is what I want to focus on. And that increased capacity leads to growing capability, which leads to succession planning. If there’s nobody to succeed to the plans and paths we set down, we’ve failed.”

Tamariki at work in the māra.

To varying degrees there have been some internal challenges from within the rūnanga; an expectation when wading into hapū politics, of course.

“I’ve had the ‘you don’t know’, ‘you haven’t been here’ and even ‘you’re just a silly little girl’, which actually made me laugh to be honest. Sexism is so dead and we’re Ngāti Irakehu tūturu; wāhine leadership is in our whakapapa,” Kelly says.

“There’s definitely been some tension and pushback to my approach and I know Jay’s felt it too. I think that’s to be expected with change. We’ll never leave anyone behind, but there are times when we need to question whether there’s resistance for the right reasons.”

Wairewa kaumātua, Theo Bunker, also an executive member on the rūnanga, has observed and even been part of gentle pushback at times. He says “it’s all part of life

and living.”

“They’re both strong leaders in their own right and aren’t afraid to challenge us older ones, which could be detrimental for some, but so far it’s tended to be opinions that we need to hear looking towards the future.

“It’s been great watching them grow; they move so quickly at times they’ve had to taihoa a bit and learn to listen to others. It’s all part of it, and they’ve got the fundamental things in place,” he says with a chuckle.

Theo was raised at Wairewa, brought up around Pā Road and the marae. His taua Molly Robinson (née Ropata) and poua Tom Robinson were both leaders within Ngāti Irakehu, the hapū of Horomaka, albeit with very different styles. Theo describes Tom as a six-foot giant, reminiscent of the marae whare tīpuna, Mako; while Molly was slight of build, “four-foot nothing.”

“Poua had a big voice and could direct people with ease. He never, ever said ‘this is for the community’ – he just did it eh, he was just in there getting it done, not talking about it. And, of course, we were expected to help. And you need leaders like that.

“My taua on the other hand had a quiet way about her. She was a midwife for everyone in our rural community; after 16 of her own, she had pretty good knowledge of birthing. She was very friendly, but whatever she said – it happened, no question. “So that’s where these two young women are coming from – their whakapapa – two very strong and complementary styles of leadership.”

“Helping whānau to build that capacity in their own whare and selves first is what I want to focus on. And that increased capacity leads to growing capability, which leads to succession planning.”

Kelly Barry.

Something that makes an impression on Theo is the cousins’ decision to hoki ki te whenua. Together with Kelly’s younger brother Nick, they have bought land back on the hill road to Koukourarata and each one lives between there and their parents’ homes in the city.

“Back in the 50s and 60s, there was the Ropata whānau, the Robinsons, the Karetai whānau, the Nutira whānau and more; we all lived out there around Wairewa. That was the time I remember whanaungatanga really being on the land,” he says.

Kelly and Jay are firm in focusing their combined energies on the intergenerational change they are influencing by drawing whānau back out to the marae – and doing that from the whenua.

A big part of that has been establishing a māra kai alongside the marae, on land also recently bought back from neighbours. Since the beginning of the year, Kelly has run the project Ahikā Kai Wairewa, and excited whānau members have been in it from the start. The biggest helpers, Kelly says, have been the tamariki who took part preparing the land, laying no-dig garden beds, propagating seeds themselves and planting.

Theo, who left Wairewa in the 1960s to pursue mahi in the city, recalls: “We used to have gardens up at Pā Road where the whole community could help themselves; potatoes, and corn. The sorts of vegetables our taua and poua prized. And they did all that hard work, from ploughing to harvesting.

“These young ones – because it’s not just Kelly and Jaleesa either, it’s a lot of them – they’re rekindling what we had, which was simple. And it was to do with the land and the kai.

Arielle Kauaeroa, Jaleesa Panirau, Kelly Barry and Béla Raiona Tohu Freudenberg.

“This māra has woken up some of these memories. It was a long time ago those sorts of things occurred, so it’s great to see we’re returning to the values of those times. Being on the land and eating off the land.”

Kelly ruminates on the different aspects of leadership she’s witnessed her elders express. And each aspect comes down to one thing, she hypothesises. “It looks like a feeling to me. There’s no one thing that makes a leader but that’s why I’ve followed people; because they helped me feel something.

“I know that our greatest guide in leading the people will always be those who came before us.

We’ll always need our older ones to look to and we value the mātauranga they share – nothing can replace that.”

Jaleesa (JAY) Panirau

“It’s so key that our whānau can see it and can feel it too. It’s not easy to create, build and sustain that feeling, but it gets stronger with every person who adds their faith, hope and intention to the kaupapa.

“Another thing I’ve observed over the many years involved with iwi and hapū is that you can’t be a leader if no-one is listening to you; if you haven’t got people’s attention. And their attention requires your energy – you’ve got nobody to lead if you do not put energy into those, you’re ‘leading’ or serving. And so, leadership requires the ability to observe, direct and influence energy.

“You could have awesome ideas and be out in the world doing all the things as an individual, but smashing out heaps of stuff doesn’t make a leader. I do believe people need to be inspired by the stuff you’re doing and feel included, because they feel like they’re doing the stuff too.”

Looking to her tīpuna is a key for Jay in contemplating leadership. Fortunate to have been raised at the ankles of her taua and poua, she deeply understands the importance of recalling the names of those tīpuna into the weaving and leading of today, and that their tapuwae – footsteps – are enshrined in the land.

“I know that our greatest guide in leading the people will always be those who came before us. We’ll always need our older ones to look to and we value the mātauranga they share – nothing can replace that.”

As wāhine Māori leadership increases around Aotearoa, it is heartening that the people of Wairewa have reflected this national trend by bringing in these two young wāhine leaders.

Tina Ngata, author of Kia Mau: Resisting Colonial Fictions, wrote in 2020 about aspects of wāhine Māori as a model of leadership. Commenting on the extreme changes we are collectively facing with COVID-19 and environmental catastrophe, she writes: “It will take the distinctive wāhine Māori leadership trait of navigating change to facilitate the radical shifts required of our political and economic systems, for us to survive. “Wāhine Māori have instinctively seen what needs to be done, and simply go about doing it.”

Since they have started in their rūnanga positions, activity at the marae has increased. The number of whānau who are newly engaged, or re-engaging, is growing with each wānanga, gardening day and kapa haka practice. This calendar year has seen a wānanga Matariki on the marae, a te reo Māori strategy rolling out with two packed wānanga and this raumati, at least 20 Wairewa whānau in Ōtautahi will be set with a weekly box of organic huawhenua.

Self-professed eternal learners, Kelly and Jay are the first ones to admit they are making it up as they go along some days – again, with raucous laughter. Kelly emphasises, “I’m following a feeling, which I admit may sound strange to some. But it’s my manawa, it’s my internal compass, and if that is strange, I’m OK with it.”