Marae Kitchen to Tribunal Hearing – Our Settlement Journey

Jul 3, 2017

He Whakaaro

Nā Ward Kamo

The death of Riki Te Mairaki Ellison (Uncle Riki) in 1984 was a watershed moment for many Ngāi Tahu. It started a torrent of Ngāi Tahu deaths, as he gathered his large ope to accompany him on his journey ki tua o te ārai. This ope included my grandmother Kui Kamo (née Whaitiri), who had been his kaikaranga at Rehua Marae in life, and would now become his kaikaranga in death. I recall Aunty Rima Bell at Tuahiwi saying the deaths would only stop when a baby joined the ope – and that appears to have been what happened. Many kaumātua at the time also stated the deaths were the first of many payments that Ngāi Tahu would be forced to make as the long journey to justice for its treaty claims neared an end.

The death of Riki Te Mairaki Ellison (Uncle Riki) in 1984 was a watershed moment for many Ngāi Tahu. It started a torrent of Ngāi Tahu deaths, as he gathered his large ope to accompany him on his journey ki tua o te ārai. This ope included my grandmother Kui Kamo (née Whaitiri), who had been his kaikaranga at Rehua Marae in life, and would now become his kaikaranga in death. I recall Aunty Rima Bell at Tuahiwi saying the deaths would only stop when a baby joined the ope – and that appears to have been what happened. Many kaumātua at the time also stated the deaths were the first of many payments that Ngāi Tahu would be forced to make as the long journey to justice for its treaty claims neared an end.

In the lead up to 1984, the then Ngāi Tahu Trust Board, under the leadership of Tā Tipene O’Regan, had been tirelessly touring Te Waipounamu drumming up support (and cash) to begin a treaty claim. The work undertaken by the Trust Board and various hapū leadership was a prescient reaction to the changing tide in race relations. The Labour Party was well placed to win the 1984 election (as it did), and had signalled it would change the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 to allow claims to be heard all the way back to 1840. The change in government, and the amendment to the Act, saw Ngāi Tahu lodge a claim under Rakiihia (Rik) Tau’s name in 1986 (Wai 27).

Nana Kui Whaitiri (left) with her cousin Wiki Reader (née Whaitiri).

Many a night, my grandmother would return from a Ngāi Tahu hui complaining of some “hara” committed by various members of the Trust Board – not least of which by Tā Tipene (the conversation at her dinner table would begin with, “That bloody Steve O’Regan…”). That’s when she wasn’t complaining about a man I only ever knew as “That bloody Joe Tu”, after she’d attended yet another Rehua Marae trustee hui (I later worked out he was the fabled Ngāi Te Rangi tohunga and Kīngitanga stalwart, Hōhua Tutengaehe). My Ngāti Mutunga Chatham Island grandfather would sit in his chair in the lounge at 99 Milton Street (a well-established halfway house for immigrant Chatham Islanders) and mutter about her being “a humbug” as my grandmother related another instance of somebody’s display of unbridled “ignorance”. No doubt many genuine tears were shed at my grandmother’s tangi – but I suspect a few may have been crocodilian.

From 1987, as the claims hearing hit full stride, Poututerangi John Stirling began a series of wānanga in Waitaha simply called “hui tāne”. He, along with our Ngāi Tahu rangatira Charles Crofts, Monty Daniels, Pīhopa Richard Wallace, and Paora Tau recognised that the treaty claims would fundamentally change Ngāi Tahu.

At the time, we attributed her death to Uncle Riki (and we were a wee bit proud that she would accompany him); the fact she’d never had a Christmas away from my grandfather (who’d passed away in January of that year); and to the countless nights my grandmother would spend either attending hui or tirelessly baking, cooking, and sandwich-making for yet another Ngāi Tahu gathering. She’d work through to 2 or 3 in the morning and then be up (if she’d even gone to bed) to head off, mokopuna in tow, to Tuahiwi, Rāpaki, Koukourārata (I hated that drive over), or even on the odd occasion down to Temuka (my grandmother’s birthplace). I would hear my Ngāti Mutunga grandfather complain to her from time-to-time that she put too much time into those “humbug Māori”. She’d huff at him as we climbed into the car driven by various aunties, or my mother and father (Mum wasn’t going to be abandoned to my dad’s Ngāi Tahu relations), and head off to the marae. My job was to carry the food around the back to the wharekai when we arrived.

From 1987, as the claims hearing hit full stride, Poututerangi John Stirling began a series of wānanga in Waitaha simply called “hui tāne”. He, along with our Ngāi Tahu rangatira Charles Crofts, Monty Daniels, Pīhopa Richard Wallace, and Paora Tau recognised that the treaty claims would fundamentally change Ngāi Tahu. More leadership would be required, and those leaders had to be versed in tikanga Ngāi Tahu. At the same time, Te Rūnaka Rakatahi was established in Christchurch. Headed by Tahu Potiki Stirling, this forum was instrumental in supporting the hui tāne. The hui tāne were underpinned by the tireless mahi of the wāhine (Aunty Aroha Reriti-Crofts, Aunty Toko Hammond, Amiria Reriti, Koral Hammond, Aunty Bernice Tainui, and Puamiria Parata te mea te mea).

By now of course my grandmother, along with many other Ngāi Tahu tāua, was gone. We’d sit at our hui tāne (we toured the Horomaka and mid to South Canterbury marae) and lament the hard work done by those old ladies. We’d talk about the pending settlements and how the money had to be allocated to marae so we could get caterers in to do the hard work previously undertaken by the tāua – “They shouldn’t have to lift a hand”, we’d stupidly state. But there was a moment out at Taumutu when Te Maire Tau warned that the settlement would have an impact on our culture that we may not like. “The money will change us,” he warned.

Dad’s (Raynol Ward Kamo) 21st party with our Nana, Sarah Thelma ‘Kui’ Kamo (née Whaitiri) and Papa Ned Te Koeti Kamo.

Nowadays the caterers do much of the work that was previously done by our tāua and Ngāi Tahu whānau. Admittedly many of those caterers are our own whānau, and that’s a good thing. But we didn’t understand then that the hard work undertaken by our tāua was a part of their Ngāi Tahu identity. It gave purpose in retirement. It strengthened their bonds to both the marae, and to us tamariki and rangatahi as we were dragged off to another boring hui where Joe Karetai would scare us (and then Uncle Riki Ellison would make us feel better with his more gentle delivery), Uncle Tip Manihera would talk way too long (when Hōhua Tutengaehe wasn’t talking way too long), where there would be some excitement as Uncle Bob Whaitiri and Kuao Langsbury brought their Murihiku and Ōtākou relations up with them, and when Tā Tipene would rise to give one of his sonorous whaikōrero.

Tā Tipene was quick to understand the importance of our tāua. He would arrive at a hui with a bevy of them. Those women were nothing more than his Praetorian Guard (I prefer the term “hitmen in gloves and hats”). God forbid if you got too much in his face. The “aunties” were brutes with tongues as sharp as knives. Many a time I recall the husky-voiced, speckle-faced Aunt Kera Brown as she would rise to her feet (and then have to stand on a chair to be seen – tall in mana but short in stature) to berate anyone who was too negative or perceived to be interfering in the mahi of Ngāi Tahu (read Tā Tipene). Aunty Kera Brown on the warpath was a sight to behold – and I subsequently found out my grandmother was as well. The “wicked witch” that both Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Mutunga ki Wharekauri refer to was in fact my most loving grandmother, who never raised her voice or hand to her very naughty mokopuna. There was the odd non-prejudiced tāua amongst them – Aunty Rima Bell being one. She was the most unbiased woman I knew – she hated everyone equally.

I relate this recent history because I fear Te Maire Tau may be right. We no longer look to the marae or hapū to represent us. Instead we have legal entities/“Incsocs” that appear to do that mahi. Our pōua and tāua appear to be nothing more than beneficiaries of our legal entity. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu has taken over much of the ground once owned by our unpaid and over-worked leadership (rangatira and kaumātua).

I attend a scattering of Ngāi Tahu hui and rarely hear stories of the marae, of the leaders, the kaumātua and the characters who strode boldly across our cultural landscape when I was growing up. My memories go back to those characters – Aunty Wai Pitama, Pat Karaitiana, Buck Robinson, Joe Waaka, Waha Stirling, Jacko Reihana, Jono Crofts, Monty Daniels (that man never failed to deliver with his stand-up routine he called a “whaikōrero” – Aunty Kaa would ignore him and talk loudly to her mates while the rest of us were rolling in the aisles) and so many more. They did the work (as so many kaumātua did), engaged in the representation, and travelled the countryside when there was no money. We grudgingly deferred to them in matters of tikanga (mumbling under our breaths about “old coots and biddies”, and being careful not to be seen or heard doing so).

But I don’t see those characters to the same extent any more. And I wonder if that’s because our settlement, and our outstanding commercial success, has come to define who we are. Have we “in gaining the whole world lost our soul”? We appear focused on cash returns, commercial performance, distributions, risk management, annual reports, not upsetting the apple cart, best person for the job, Iwi Leaders Forums, myriads of other forums, and so on. And I was (and remain) part of that – I worked for both Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Ngāi Tahu Holdings Corporation.

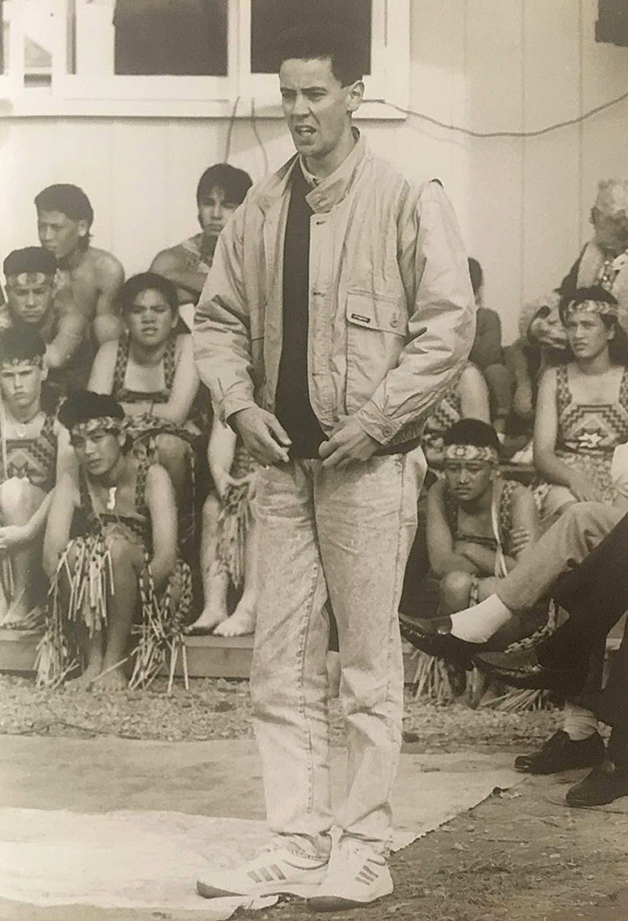

A young Ward Kamo.

So, it’s 21 years on since 1996 and the passing of the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Act. We have changed – how could we not? The marae have changed – make no mistake. But is it all bad? I hear a level of reo spoken today by our rangatahi (and some of my contemporaries) that was never there other than with my kaumātua when I was growing up. Most of our Ngāi Tahu people no longer spoke the reo back then. My grandmother did because she’d learnt so much of it from her Ngāti Mutunga ki Wharekauri whakapapa (where it was still spoken as a first language by my grandparents’ generation). And she had the accent to prove it (Aunt Jane Manahi always teased her about her “areare mai, areare mai” when she would karanga at Tuahiwi).

Yet within that lovely reo, I don’t hear the stories of people both current and past. I hear exquisite tauparapara, eloquent kōrero on the issue being discussed, wonderful waiata to finish it all off. But I don’t hear the references to names of people past who shaped who we are today. Growing up it was a rare whaikōrero, or subsequent kōrero once formalities were concluded, that didn’t reference tīpuna. And not tīpuna of centuries past – but rather of the previous generation.

Whakapapa underpins all that we are about as a people. Whakapapa is not a genealogy – whakapapa is a compendium of all the stories of people that made us who we are today.

Names constantly referenced (at least in Waitaha – sorry my southern whānau) included Jim Pohio, Te Ari Pitama, Pani Manawatu, Eruera and Amiria Stirling (all the way from Te Whānau ā Apanui), Pōua Tikao (Te One), Tame Green, Pōua Pani, Matiaha Tiramorehu, and Tāua Fan Gillies. And no kōrero started at Arowhenua without the names “Kukuwhero and Tarawhata” leading off. Some of them I’d met – many were gone before I was born. And yet I knew them. I knew them because I was exposed to the marae and hapū where these names were kept alive.

This knowledge was held within the people who made the sandwiches, baked the cakes and scones, and cooked the boil-up. The tāua would sit on the seats outside the wharenui and call me over and ask, “Who are you?” And I would reply “I’m Ward Kamo, Ray Kamo’s son”. And the tāua would say to each other, “Oh, that’s Mary’s boy, Kui’s moko.” I’d be quickly forgotten, but the conversation would turn to the exploits of my grandmother. From there, the conversation would spin off to other mokopuna and their tīpuna – and I lapped it all up.

Whakapapa underpins all that we are about as a people. Whakapapa is not a genealogy – whakapapa is a compendium of all the stories of people that made us who we are today.

The story of Ngāi Tahu is not the story of returns on investment, Go Bus, TRONT, pūtea tautoko, and the “tēpu”. It is not a story that began 20 years ago with the passing of legislation “establishing” us. It is the story of my grandmother Sarah Thelma Kui Whaitiri, and her mother Mereana Ngapohe Rakatau, and her grandmother Hera Kume Ihakara, and her great-grandmother Arihia Pohe Whaitiri, and her great-great-grandmother Mereana Taimana, and her fighting great-great-great grandmother Hinehaka Mumuhako – for which there may not have been a kai huānga feud had her whānau not been killed at Taumutu, and for which she raced down to Murihiku to tell her husband Te Wera and her whanaunga Te Matenga Taiaroa, and who composed her famous waiata about Taununu (my Rāpaki tipuna).

And so I combine my story with the stories you have of your Ngāi Tahu grandmother, and your great grandmothers, and great-great grandmothers, and so on. And we tell each other these stories of who we are. And we debate with each other, and accuse each other’s tīpuna of treachery, and call the previous generation “bloody fools” and the future generation “so ignorant”, and eye up our whanaunga and laugh, and drink, and eat the food those tāua stayed up till 3 o’clock in the morning preparing for us.

That’s the story of Ngāi Tahu. That’s who we are!

Ward Kamo (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Mutunga Chatham Island, and Scottish decent) grew up in Poranui (Birdlings Flat) and South Brighton, Christchurch. Leaving University with a BA and PG Dip in Natural Resources, Ward’s career path has been varied, at times eye raising, and ultimately rewarding.

He has worked with Te Rūnanga o Ngai Tahu (Ngai Tahu Holdings Corporation), and the Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri Iwi Trust as General Manager. He is currently working with Bayleys as National Director of Tu Whenua – the Bayleys Māori business division.

Ward will be a regular columnist in Te Karaka offering a perspective on issues and politics of significance to Māori.