"Picturing" Kāi Tahu in 1830's Poihākena: A Preliminary Sketch

Dec 21, 2021

Nā Dr Michael J. Stevens (Ngāi Tahu Archive)

rāua ko Dr Rachel Standfield (University of Melbourne)

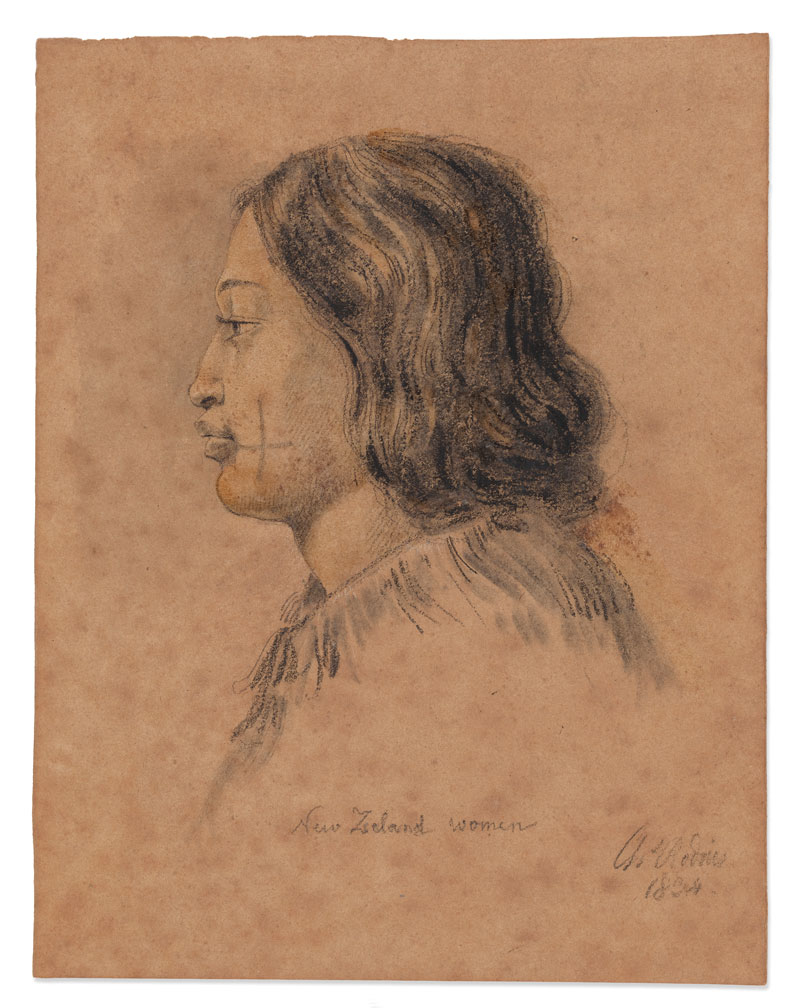

Above: “New Zealand woman,” 1834. A side profile of “Adodoo” pictured on page 17. Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

In December 1834 three young Kāi Tahu visitors to colonial Sydney sat before a german-born French artist. Using charcoal, graphite and watercolours, the man produced a series of head and shoulder portraits that capture the trio’s natural beauty and their tā moko. Who are these tīpuna and why were they in Sydney? Who was this artist and why was he in Sydney? And what is the enduring significance of their encounter?

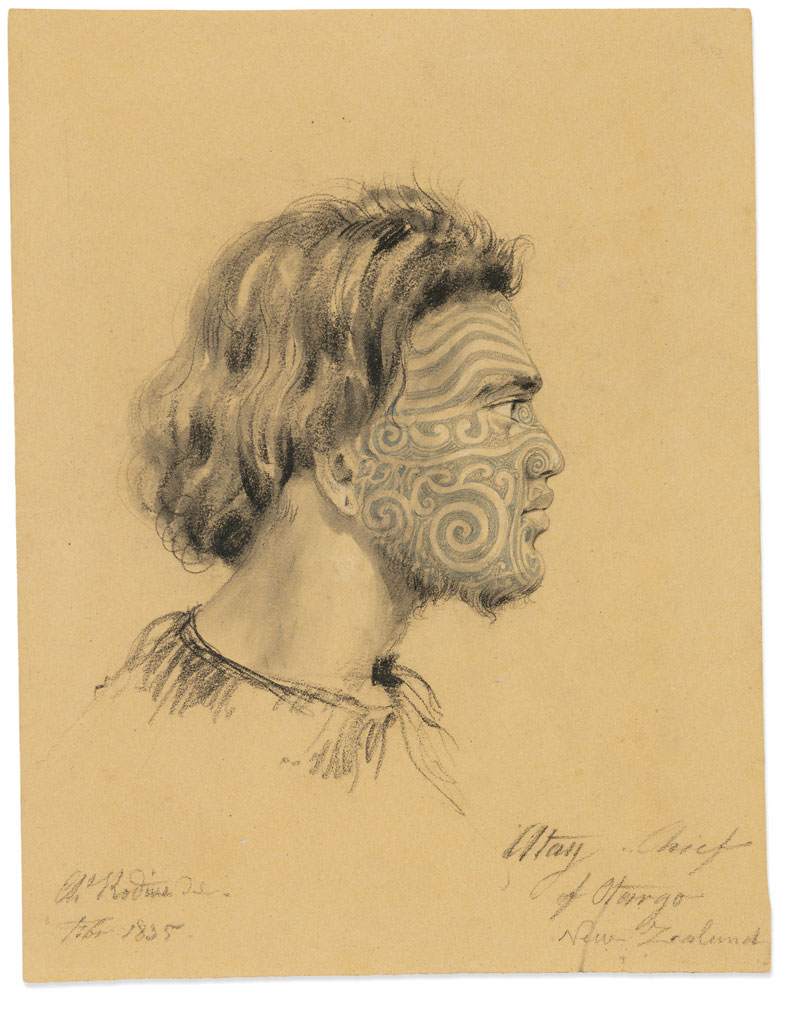

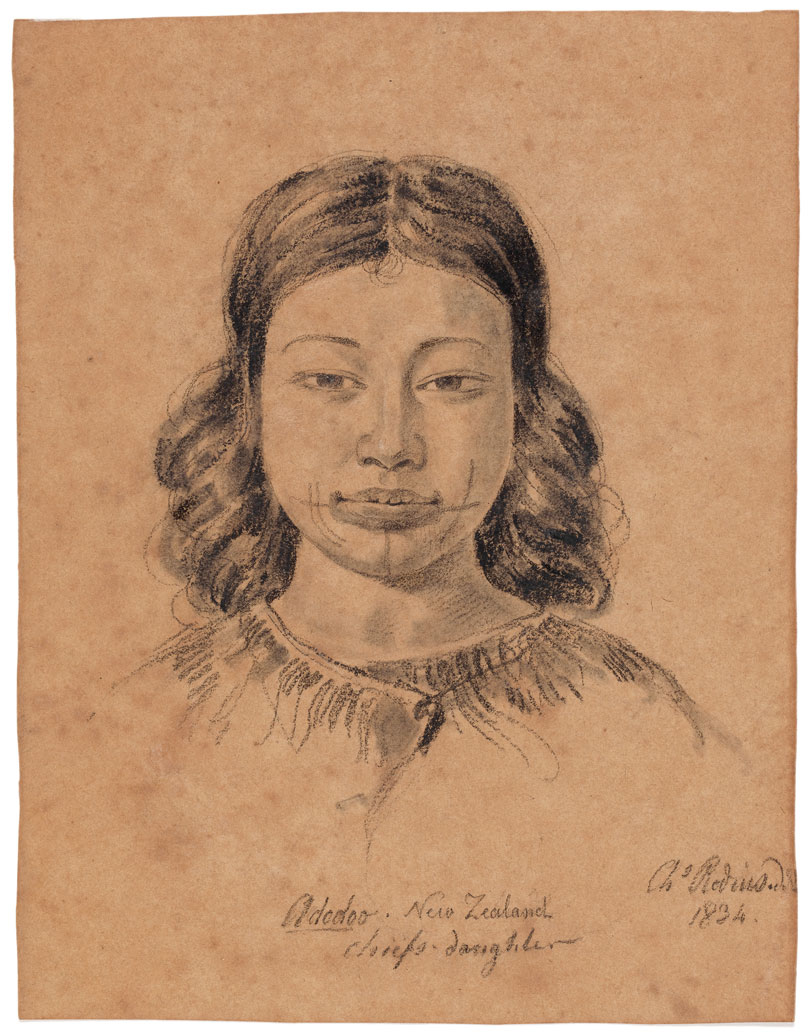

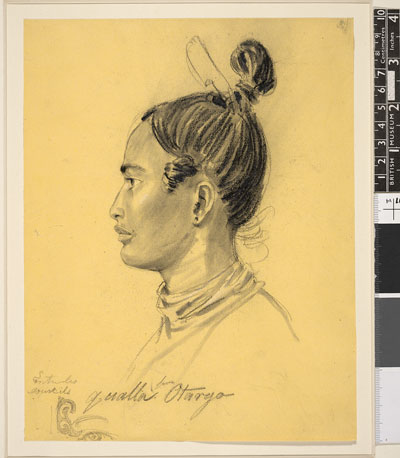

One of the subjects is clearly male, recorded as “Atay, Chief of Otargo.” Another is clearly female, “Adodoo”, a “chief’s daughter”, who was drawn from two perspectives. The remaining person is described as “Qualla from Otargo.” This person, whose side profile was captured, looks quite feminine, however is currently recorded as male.

They were three of several Kāi Tahu people who travelled from Te Waipounamu to Sydney in the 19th century: a line of travel that continues, unbroken. The artist in question, Charles Rodius, was a convict who sketched and painted portraits of well-known NSW colonists and landscapes. As far as we can tell, he made five images in total of three Kāi Tahu individuals. He also had published two series of lithographic prints of notable Aboriginal people – males and females.

Born in 1802 in French-occupied Cologne, Rodius trained as an artist and architect in France, and reputedly produced engravings of Parisian buildings. He subsequently moved to England where, in 1829, he was convicted for theft and transported to NSW. Forced to work as an unpaid architectural draughtsman until 1834, he also took drawing classes before receiving a certificate of freedom in 1841. An 1834 article in the Sydney Gazette described his prints of “aboriginal chiefs and their wives” in glowing terms. “The fidelity of the likenesses,” it assured readers, “will at once strike every beholder who has been any length of time in the colony.” However, Rodius was more than just highly-skilled. His portraits were sympathetic representations of indigenous people, even as he catered to the frequently dehumanising demand for images of “exotic” people (the Gazette noted his Aboriginal “drawings would prove very acceptable present [sic] to friends in England.”)

This combination of artistry and sensitivity means that Rodius’s renderings of indigenous people can be considered valuable sources of ethnographic knowledge. In terms of the Māori people he met, his careful reproductions of tā moko and references to homeplaces and personal names (albeit phonetically), can be cross-referenced with whakapapa knowledge and shipping records to potentially identify specific tīpuna.

What then, do we know about “Atay”, “Qualla” and “Adodoo”? They were not the first Māori, nor even the first Kāi Tahu, to lay eyes on colonial Sydney. An ope from Ruapuke Island and Awarua sailed to Poihākena (Port Jackson) more than a decade earlier, in 1823, on board the cutter Snapper. This group, which included Tokitoki and her husband James Caddell, and probably a young Tūhawaiki, witnessed the expanding frontier from its core. Hungry for the New Zealand archipelago’s seal-skins, timber, flax, whale bone and oil, this maritime trade web coalesced into a “Tasman World”; an offshoot of a larger Australian “Pacific Frontier” that also drew in Tahitian pork and Fijian sandalwood.

This regional network, which was part of the expanding “Second British Empire”, brought the Kent-born, Sydney-based Weller family merchants to Ōtākou in 1831. It also brought men like Aboriginal whaler Tommy Chaseling (commonly rendered as Chaseland), Irishman James Spencer, Englishman William Stirling and Scotsman James Joss to southern Murihiku. As well as potatoes, pigs and clinker dinghies, these people – collectively referred to in southern New Zealand as tākata pora – brought names to Te Ara a Kiwa and adjacent islands such as Foveaux, Henrietta, Bunker, Paterson, Lord and Bungaree. The latter, incidentally, was a well-known Aboriginal man who Rodius drew a few years before producing the Kāi Tahu portraits.

Above: “Atay Chief of Otargo New Zealand,” 1835. A detailed portrait probably based on the sketch on page 18. Courtesy of Hocken Library, Dunedin.

As with iwi and hapū in the northern North Island, growing trans-Tasman shipping movements enabled several Kāi Tahu to visit Sydney in the 1830s and early 1840s. Among these were kā rakatira Taiaroa, Karetai, Tūhawaiki, Haereroa, Kaikoareare, Pokene and Topi Patuki. These visits were mostly self-directed – expressions and consolidations of mana – but that was not always the case.

In July 1834, with interracial tensions running high at the Ōtākou whaling station, Captain William Anglem enticed Karetai (known to whalers as Jacky White) and a few more of the haukāika on board the Lucy Ann and surreptitiously set sail for Sydney. The barque arrived at Poihākena with a cargo of whale oil and bone, three tonnes of potatoes, and coal samples. The ship also carried news “of the natives shewing [sic] a hostile disposition to the Europeans.”

Consequently, as the Sydney Herald put it, “Captain Anlgim [sic] was obliged to detain on board several New Zealanders as hostages for good behaviour of the natives near Otago.”

A large ope taua had arrived at Ōtākou after the latest round of fighting with Ngāti Toa and allied iwi in the Tauihu region and, according to Anglem, “treated the [European] residents with much insolence.” They physically assaulted one of the Weller brothers and plundered whalers’ houses. In the midst of this a highborn child died, which was “attributed to the visit of the Lucy Ann”, for which violent utu was apparently to be sought. In response, “For the better security of the lives of the residents at Otago, and its neighbourhood”, Anglem took Karetai and others on board “as hostages for the good conduct of their tribe during the absence of the Lucy Ann.”

Along with three Trans-Tasman traders, including Joseph Weller, Anglem subsequently signed a petition to the NSW Governor complaining about the lack “of protection afforded to those engaged in the trade to New Zealand” and asserting the need “to check the increasing hostilities of the Natives.”

Backhouse’s letter to Buxton, dated February 5 1835, explained that he met “a New Zealand chief” a few days prior who, “with his wife and one or two children” were “detained as a hostage by … the firm

George Weller & Co … who have a profitable whaling establishment … on … the coast of New Zealand to which this man belongs.”

By mid-October 1834, by which time Karetai and his fellow captives had been in Sydney for more than two months, the Joseph Weller returned to Poihākena from Ōtākou. The ship’s master told the Sydney Herald: “The natives are continuing their depredations upon the Europeans in this part of New Zealand” and the Weller family were looking to exit their operations there. The schooner also delivered a letter from the whaling station itself, which the newspaper published. According to this, a group of rakatira, including Te Whakataupuka and Taiaroa, assured resident whalers they would all be murdered as soon as the Lucy Ann returned with “the two Chiefs which went up in her.” This was unfortunate news for the Sydney hostages, as it ensured their continued detention. While Sydney’s merchants clearly considered this necessary and justifiable, the settlement’s leading missionaries disagreed. Two of them, James Backhouse and Samuel Marsden, wrote to British MP Thomas Fowell Buxton, a prominent opponent of the slave trade and advocate for indigenous people within Britain’s formal and informal territories.

Backhouse’s letter to Buxton, dated 5 February 1835, explained that he met “a New Zealand chief” a few days prior who, “with his wife and one or two children” were “detained as a hostage by … the firm George Weller & Co … who have a profitable whaling establishment … on … the coast of New Zealand to which this man belongs.”

Backhouse and Marsden considered the situation illegal and an impediment to, rather than a means of, peaceful relations with Māori. Marsden penned his own message to Buxton six days later.

Drawing attention to abuses that visiting ships’ crews had inflicted on Māori, Marsden pointed out their inability for redress other than “some act of violence on an innocent European.”

Referring to Karetai and whānau, he added: “I have had a chief and his wife with me lately [at Parramatta]; they have been some months in the colony … brought … in a whaler belonging to a mercantile house at Sydney.”

According to Marsden, the couple met the Governor and believed they had secured a passage back to Ōtākou. However, the missionary later “met the chief and his wife in the streets of Sydney” and learned the intended vessel sailed without them. According to Marsden, “The poor woman wept much about her children, telling me that she had left three in New Zealand, and she was fearful they would all die.” Curiously, unlike Backhouse, Marsden does not refer to anyone other than Karetai and his wife, let alone their children.

Above: “Adodoo. New Zealand chief’s daughter,” 1834. Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

Several weeks later the couple was still in Sydney and described as “unwell”. This might be a reference to a state of understandable depression: “I am afraid the woman will die of grief,” he wrote. It could equally be a reference to one or both contracting measles, which was by then at epidemic levels after arriving at Poihākena three months earlier. Marsden visited the Weller family and colonial authorities and pleaded a case for Karetai, to no apparent effect.

But perhaps Marsden’s efforts had some impact. A month later, in early March 1835, the brig Children was chartered to transport supplies to Ōtākou, and also carried eight passengers. One was the whaler William Sterling [sic] who would soon establish a whaling station at Bluff. Another four passengers were “New Zealanders”, that is, Māori: “Wakahau, Jackey [sic] White, wife and child.” George Weller subsequently wrote to his brother Edward at Ōtākou explaining: “I have sent Jacky White and family who have been very troublesome and urgent to get down again.”

Unfortunately, this was not a happy homecoming. People on board the Children, including, it seems, Karetai and his whānau, were sick with measles. The vessel called in at Ruapuke Island and then Ōtākou, infecting people at each place. In November 1836 the Sydney Herald reported 600 Kāi Tahu individuals had died. To make matters worse, another ship, the Sydney Packet, introduced a strain of influenza to Ōtākou that October. This, coupled with tuberculosis, reduced the Kāi Tahu population in the decade immediately prior to colonial settlement beginning at Dunedin.

In retrospect, the mid-1830s were a pivotal time for Kāi Tahu, but also for the Tasman World. This was when wool replaced whaling and sealing products as the main exports from NSW, signalling a decline in the importance of the extractive maritime economy that helped give rise to the Tasman World. It was precisely at this moment that Charles Rodius sketched three Kāi Tahu individuals, alongside, it appears, two Māori from Te Ika a Māui. So, who are these tīpuna of ours? Who are “Atay”, “Qualla” and “Adodoo”?

Some might suggest “Atay” is Karetai himself. However, we think this unlikely. For starters, the tā moko Rodius recorded is much larger and more detailed than that sketched in William Fox’s 1848 water-colour of Karetai. Also, Karetai was in his mid-fifties during his roughly eight-month stay at Sydney, whereas Atay is clearly a younger man. Might then have Atay been “Wakahau”? Perhaps. In any event, we think that name is properly Waikaihau: a name closely linked with the Karetai whānau that appears in successive generations. As for Adodoo, Karetai is probably her father – given she is described as a chief’s daughter. However, there are other explanations. She could, for example, be one of his several wives, but we doubt that.

According to his biography, Karetai had at least eight wives: Pōhata, Hinehou, Pītoko, Te Kōara, Wahine Ororaki, Māhaka, Hinepakia, and Te Horo. Conscious that ‘r’ was often heard as an ‘l’ in our southern reo – as demonstrated by Rev. Watkin’s 1840s vocabulary of southern Kāi Tahu reo – we suggest that Qualla refers to Kōara. If that is correct, then “Qualla” is female, and the British Museum’s description of this person as male, which is seemingly based on an archivist’s assumption, is incorrect. If we are right, this strongly suggests that Adodoo is a daughter, or at least step-daughter, of Te Kōara. According to one descendant of Karetai and Te Kōara, the latter’s mother and father were Pipiriki and Waikaihau, respectively. That raises the possibility of Te Kōara having been in Sydney with her father, husband and child. But this is all very much speculation, and points directly to the crucial importance of whānau knowledge of whakapapa including spousal names, marriage chronology, and tā moko.

The Adodoo portrait is remarkable for its distinctive moko. This may well be an example of the southern Kāi Tahu variant of dots or lines running along or across cheeks, especially on females. Several of Herries Beattie’s Kāi Tahu informants described this style.

We know that some tīpuna names get lost from whakapapa – if individuals died without issue, or succeeding generations subsequently ended – even as such knowledge was being transformed into written forms from around this time.

“Atay”, “Qualla” or “Adodoo” could have conceivably perished during the 1835 measles and flu epidemics and their cultural memory might have accordingly diminished or even vanished. If so, that makes their images and experiences no less important to our understanding of our collective Kāi Tahu history. For example, the Adodoo portrait is remarkable for its distinctive moko. This may well be an example of the southern Kāi Tahu variant of dots or lines running along or across cheeks, especially on females. Several of Herries Beattie’s Kāi Tahu informants described this style. An oil painting and photo of Tarewaiti (“Waimea”/Sarah) Sherburd of Rakiura, who died in 1901 at apparently 100 years of age, are other rare surviving examples.

Why are we, two historians, interested in these portraits? Because they form part of our contribution to a major research project funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC). Entitled Indigenous mobilities to and through Australia: Agency and Sovereignties, this multi-year study is being undertaken by an interdisciplinary team of Aboriginal, Pasifika, Māori and non-Indigenous scholars. Rachel, a white Australian, is one of these researchers, along with Mike, who brings his Kāi Tahu expertise and that of the Ngāi Tahu Archive and Te Pae Kōrako. In broad terms, the ARC project explores historical and contemporary events, issues, politics and knowledge concerning Indigenous mobility in relation to Australia. The project will extend our earlier work that explored Kāi Tahu migration to Australia, which we have recently published. This shared interest began in earnest over a decade ago when we each completed a PhD in History at the University of Otago – Rachel on racial tropes in the Tasman World and Mike on te hopu tītī, the seasonal muttonbird harvest. We were then, and are still now, strongly influenced by Tā Tipene O’Regan’s observation that for Kāi Tahu: “the voyage west has always been more attractive … than the journey north.”

We are keen to further identify and analyse Kāi Tahu cultural encounters in colonial Sydney, and Australia more broadly. Of particular interest are interactions between Kāi Tahu individuals or whānau with other Māori in Australia, and with Aboriginal individuals or groups – whether in indigenous or colonial settings. However, the extent to which any of this is captured in archival sources – overwhelmingly the creation of white, elite males – remains unclear. However, Rodius’s evocative images – of Aboriginal and Māori males and females – hint at tantalising indigenous connections. As such, we hope to extend the work of the late Fijian-Australian historian Tracey Banivanua Mar and her focus on Sydney as a transit point and meeting place for indigenous people. She stressed that Sydney was “located at the convergence of numerous paths” taken by indigenous peoples in the region “as they sought to resist, manage, or exploit emerging colonial settlements and trades”, and asserted that archives can reveal connections there between “Pacific Islander, Māori and Aboriginal people [who] lived and worked side by side in an uneven but persistent convergence of experiences”. That said, we remain alive to the possibility that Rodius’s portfolio of indigenous portraits may simply represent connections within the archive itself, rather than relationships between people the artist drew.

If we agree that Kāi Tahu history occurs wherever Kāi Tahu people are, or have been, then historians of the Kāi Tahu past must retrace those footsteps. In addition, it is important to connect those historical patterns of movement with present-day Kāi Tahu mobilities. On that note, we would love to hear from Kāi Tahu whānau with any information about people featured in Rodius’s drawings, or other historical Kāi Tahu figures who visited Poihākena in the 19th or 20th centuries…

Above: Portrait of “Atay Chief of Otargo New Zealand,” 1834.

The image on page 14 was probably based on this sketch.

Either way, we want to unpack the significance of Kāi Tahu travel to Australia – then and now – for Kāi Tahu, as opposed to what colonial administrators, contemporary politicians, academics, or even present-day rank-and-file Australians make of this subset of trans-Tasman Māori movement. In doing so we think Australia’s historical consciousness, as well as New Zealand’s, can be usefully enlarged. And, of course, many present-day Australians are in fact Kāi Tahu, some of whom are tightly connected into Aboriginal, pan-tribal Māori, or Pasifika communities, including by blood. We hope those whānau might be particularly interested in the antecedents of their lived experiences.

We also think our project and approach is important for the haukāika: those who remain firmly embedded in heartland Kāi Tahu village communities. In a 2004 article on colonial administrator Joseph Foveaux, the Australian historian Anne Marie Whitaker criticised historians of early NZ for overlooking documentary sources located in NSW and further afield. With that in mind, if we agree that Kāi Tahu history occurs wherever Kāi Tahu people are, or have been, then historians of the Kāi Tahu past must retrace those footsteps. In addition, it is important to connect those historical patterns of movement with present-day Kāi Tahu mobilities. On that note, we would love to hear from Kāi Tahu whānau with any information about people featured in Rodius’s drawings, or other historical Kāi Tahu figures who visited Poihākena in the 19th or 20th centuries, because while the colonial archive might tell us something about people like Rodius, it is more likely Kāi Tahu whānau are able to tell us about the lives and travels of various tīpuna.

Reflecting the colonial networks that gave rise to Rodius’s portraits in the first place, and enlarged and constrained indigenous movement to and within colonial NSW, these Aboriginal and Māori images are now scattered throughout the world. Key public repositories include the British Museum and State Library of NSW. In December 2017 Dunedin’s Hocken Library was added to that list when it purchased a portrait of Atay from the Auckland branch of the short-lived trans-Tasman auction house, Mossgreen-Webb, for $158,000. Previously part of a private Melbourne collection, Te Rūnanga o Ōtākou formally welcomed the portrait to the Hocken Library in July 2018 after it underwent restoration work.

The Hocken Library’s portrait is dated 1835. Remembering that Wakahau returned to Ōtākou in early March that year, this date might mean it was completed immediately before the Children set sail from Poihākena. That seems unlikely in light of the measles epidemic. So, given that the portraits of Adodoo and Qualla are dated 1834, Atay could have been a later Kāi Tahu visitor, and not part of the hostage grouping – not Wakahau. While not impossible, it appears improbable. This is because the British Museum also holds a version of the Atay image – something of a working drawing – which is dated 1834. We therefore speculate that Rodius used this sketch to complete the more polished 1835 portrait.

What happened to Rodius and Karetai in the years after their probable encounter in Sydney? Rodius married twice, both wives apparently dying young. He had a son to his first wife, but nothing was known of his family at the time of his death, aged 58. This occurred at Liverpool Hospital, southwest of Sydney on April 9 1860, after suffering a serious stroke in the late 1850s. Buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave at Pioneers Memorial Park, his Māori and Aboriginal portraits are one of the few things keeping his memory alive.

In January 1840, Karetai returned to Poihākena, this time with Tūhawaiki and other leading southern rakatira in connection with potential large land sales. This was immediately before the first signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, which Karetai signed a copy of at Ōtākou in June. He was also party to land-sale negotiations and a signatory to deeds between 1844 and 1853, and added his name to an 1857 petition highlighting Kāi Tahu mistreatment by the colonial state.

Above: Portrait of “Qualla from Otargo”, 1834. Possibly Te Kōara, a wife of Karetai.

Karetai re-assumed his mantle of leadership at Ōtākou in 1835, after which relations with the Weller Brothers’ whaling station improved markedly, continuing to operate until 1841. In late 1839 he commanded four of the 20 boats that unsuccessfully attempted to engage Te Rauparaha and Ngāti Toa in battle. In January 1840, Karetai returned to Poihākena, this time with Tūhawaiki and other leading southern rakatira in connection with potential large land sales.

This was immediately before the first signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, which Karetai signed a copy of at Ōtākou in June. He was also party to land-sale negotiations and a signatory to deeds between 1844 and 1853, and added his name to an 1857 petition highlighting Kāi Tahu mistreatment by the colonial state.

Karetai died at Ōtākou aged 79 on 30 May 1860 – seven weeks after Rodius. But unlike Rodius, he was, and remains, surrounded by descendants. Not only is his grave marked, his headstone is a prominent feature of the urupā above Ōtākou Marae, and his memory is cherished by his whānau and iwi, who live and work in every corner of the Tasman World.

Further reading:

Harry Evison, “Karetai (1781?-1860)”, in Helen Brown and Takerei Norton (Eds). Tāngata Ngāi Tahu: People of Ngāi Tahu (pp.12-20). Christchurch: Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, and Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. Available here: https://media.kareao.nz/images/Public/Text/2017-0274%20-%20Karetai_BIO%20V2.pdf

Rachel Standfield and Michael J. Stevens, “New Histories but Old Patterns: Kāi Tahu in Australia” in Victoria Stead and Jon Altman (eds), Labour Lines: Indigenous and Pacific Islander Labour Mobility in Australia, ANU Press, 2019, pp. 103-131.

Available here: http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n5654/pdf/ch05.pdf

Michael J. Stevens, “‘A Defining Characteristic of the Southern People’: Southern Māori Mobility and the Tasman World”, Rachel Standfield (ed) Indigenous Mobilities: Across and Beyond the Antipodes, Canberra, ANU Press, 2018, pp. 79-114.

Available here:http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n4260/pdf/ch04.pdf

Robert Stevens, “Charles Rodius, convict artist”, Australiana: Researching, Preserving and Collecting Australia’s Heritage, February 2020, Vol. 42, No. 1.

Available here: https://www.stgeorgeseastivanhoe.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Rodius.pdf

Tracey Banivanua Mar, “Shadowing Imperial Networks: Indigenous Mobility and Australia’s Pacific Past”, Australian Historical Studies, 46:3, 2015, pp. 340-355.