Pots of gold

Apr 15, 2012

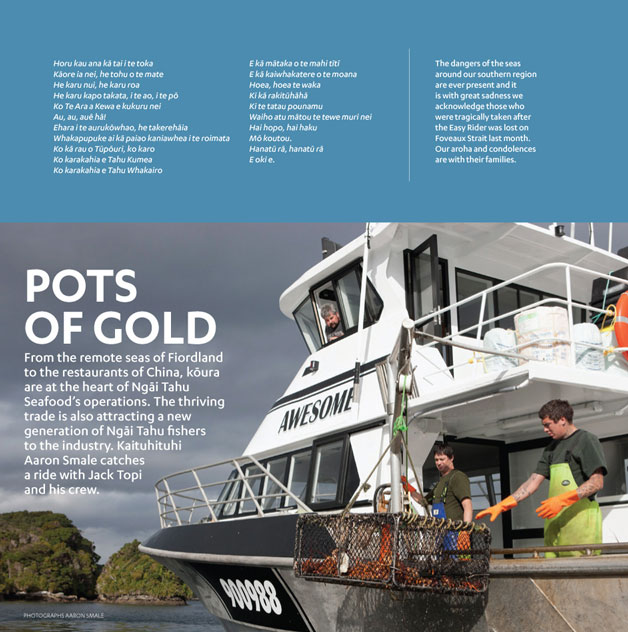

Jason and Dylan Ryan lift a craypot in Dusky Sound while Jack Topi watches on from the wheelhouse.

Several albatrosses hover on the wind as ocean waves crash against the rugged Fiordland coast. A boat named Awesome pitches sideways as owner and skipper Jack Topi slows down for another cray pot. A wave hits the side of the boat and surges on to the deck.

Dylan and uncle Jason (aka Stinger) Ryan set a steady rhythm: hooking the rope of the craypot buoy, winching the pot aboard, emptying the spiky orange and crimson catch into a bin, baiting the pots, and dumping them back overboard. The toot of a horn marks the GPS point to return to the next day.

In between gathering pots the Ngāi Tahu crew sorts the catch: too big – over the side, too small – over the side. Then there’s the close inspection for any signs of eggs on the tails. If eggs are found, those kōura also go over the side, to populate the next generation.

Jack Topi steering Awesome.

The careful and almost tender way the kōura are handled reflects their value. When a huge eel is emptied out of a pot into the bin and starts thrashing amid the kōura, the air turns blue with curses. Kōura with broken legs can be rejected, so the eel is literally tearing up money.

A mid-sized cray, the most sought after, will tip the scales at around a kilogram. A landed kilo is worth $50 to $120. This is good news because skipper Jack (Ngāi Tahu) has bills to pay. His fuel bill for the previous month was over $20,000. His boat cost him $500,000 and its refit over $1 million.

“She’s never tied up. I’m going hard to keep the bank happy. As long as China keeps buying …” he says, underscoring the importance of this crucial market.

The Chinese appetite for kōura seems unlikely to wane any time soon. In a sign of shifting global fortunes, China has become Ngāi Tahu Seafood’s mainstay market for this most valuable product. In the 1980s, the United States was the main buyer, and wanted only the tails. Then the live kōura market became established, with Japan leading the way.

Colin Topi leans on a bollard in Bluff Harbour.

Jack’s father, Colin, says in the beginning there were doubts that exporting live kōura was even possible.“When the live [cray]fish first came in, we didn’t think the West Coast would be able to handle it, because how do you get the fish out of the West Coast alive, to go into tanks?

“Well, it didn’t take long and they were flying them out by helicopter.”

Colin says the kōura were being fished out of 20 to 60 metres of water, put in a case, flown over the top of the alps, plonked back down on ground level, put in a tank, trucked for two hours, put in another tank of water, trucked for another eight hours, swum again and then flown to Japan. “No one thought they’d last that long but they’re doing it. So they’re a good hardy species to deal with.”

Hardy, but not inexhaustible. Colin, who in October retired from the board of Ngāi Tahu Seafood, was fishing in the heyday when the word sustainability hadn’t been heard of, much less practised.

“Once upon a time it was rape and pillage. Now it’s about looking after the industry. If we had’ve kept going the way we were when I first started, there would be nothing left.”

In the late 1980s, when the fishery was showing signs of collapsing, the government stepped in with the quota system based on the catch history of each fisherman. Fishermen were allocated quotas based on an average over several years.

At the time, it was somewhat contentious as to who had been fishing what and for how long. Those debates are history now, but the resulting shakedown saw some leave the industry. Access to quotas, either through ownership or lease, is now as fundamental in running a fishing business as having a boat. And fishermen, if they think it is necessary, will often recommend to authorities that quotas be cut back for a season.

For many Ngāi Tahu families in Bluff, fishing is not just a career or industry, but a way of life.

Colin’s tūpuna Topi Patuki moved down from Christchurch and settled on Ruapuke Island. He was among the last of the traditional rangatira in the area. For him, fishing would have been a necessity rather than an option.

Colin and his wife Lynne’s house overlooks the entrance to Bluff Harbour. Their lunch conversation is punctuated with glances over the water, and comments on wind direction and boat movements. Only the week before, the cargo ship Rena had been in port. Its slow demise near Tauranga has been watched with interest.

Jack and brother Tristan both fish, and Jack remembers the sea as a backyard playground when he was a kid.

“We’d go away on the family boat to Stewart Island at Christmas time. It’s a good lifestyle. Once it’s in your blood it’s hard to get it out.”

After leaving school he worked in fish factories, learning knife skills and market quality requirements. He worked as a crewman on his father’s and other boats, catching sharks and oysters as well as kōura.

“Eventually I jumped up to the mark and got my ticket, and ran (Colin’s) boat for about eight years. Then he wanted his one back, so I went to Aussie and bought this one.”

Lynne sees the tradition carrying on for the following generation, and says it’s imperative to protect the resource for those to come.

Kōura bound for the Chinese market.

“We’ve got three grandchildren and the boys are always down on the boats, so I think it’s inevitable they’re going to be there too. It’s their way of life.

“It’s up to us to make sure the sustainability is there. We’re just kaitiaki and it’s up to us to make sure we leave the industry as good if not better, than we’ve got it now. We’ve just got to keep adapting to the resource that is there, to ensure sustainability.”

Jack says the biggest influx of young fishermen has actually been Ngāi Tahu, because of the development pool in Bluff. Lynne points out that the benefit is not just to the fishermen but the entire community of Bluff and beyond.

“The Ngāi Tahu fishers here in Bluff, the benefits of that asset filter right through our community and outside of it, through the workers in the factory, the shops, the whānau. It’s our whole community, Ngāi Tahu fishing. It’s not just the fishermen going out onto the sea in the boats and the crew on those boats. It’s their whole community on the shore as well. It’s who we are.”

That loyalty has taken time to build. Each party must continually reassess to remain competitive. Colin remembers a time when Ngāi Tahu Seafood wasn’t the first choice for fishermen.

“Ngāi Tahu, years ago, before I started fishing for them, never had a very good name overseas for the quality of their fish. A lot of those who used to work for two companies would put all their good fish into the other company and Ngāi Tahu used to get all the rubbish. It’s changed now. You’re not getting any more for it but you’re selling more because they want that quality.”

He says Ngāi Tahu has met that challenge and the quality of its fish has come up.

Lynne also believes the concept of Ngāi Tahu as a family is a strong selling point.

“China is very family-orientated. My belief is they need to market that; they need to build that relationship – family supplying family. I think it’s really imperative.”

The seas of Fiordland can get rough, but they’re a millpond compared to the volatile world economy fishing businesses operate in. A global financial crisis, coupled with a high dollar, is never a great time for any exporter, let alone one based on a primary industry. But despite these and other factors, Ngāi Tahu Seafood has increased its profit, netting $13 million in the 2010 financial year and $16 million in the 2011 financial year. However, no one involved in the company is taking anything for granted.

After all the pots have been emptied, Jack pulls the boat into Dusky Sound and parks up. The waters are calm, and the surrounding mountains look much as they did hundreds of years ago to Ngāi Tahu tūpuna.

“There’s probably not too many people who can say they love their job. But I do, that’s for sure,” Jack says.