ReviewsBooks

Jul 7, 2016

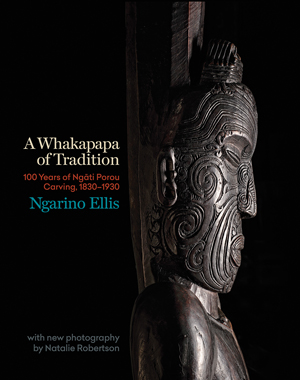

A Whakapapa of Tradition: 100 Years of Ngāti Porou Carving, 1830–1930

Nā Ngarino Ellis

Auckland University Press

RRP: $69.99

Review nā Professor Ross Hemera

Another book about Māori carving is a welcome addition to the growing list of publications about Māori art and those written by Māori women. It is also of interest that this book focuses on a particular locality and practice of the East Coast. While the Iwirākau tradition of the Waiapū Valley represents a relatively short period in history, and a relatively small geographic area, its impact resounds loud and clear today.

Another book about Māori carving is a welcome addition to the growing list of publications about Māori art and those written by Māori women. It is also of interest that this book focuses on a particular locality and practice of the East Coast. While the Iwirākau tradition of the Waiapū Valley represents a relatively short period in history, and a relatively small geographic area, its impact resounds loud and clear today.

Throughout the book there is a treasury of photographic images, which provide both context and illustration for the text. Impressive and arresting photographs by Natalie Robertson adorn several pages. It is a pity, however, that some of these are subject to the distraction and visual imposition of the double-page spread syndrome.

The book is liberally punctuated with quotations from a wide range of leading Māori and European scholars, academics, and commentators on Māori art and culture. In particular, Ellis has made use of expert Māori art analysts such as Roger Neich and Robert Jahnke to add an authoritative basis to the commentary.

The book uses architectural examples to trace the advent of the whare whakairo or carved meeting house, including the waka taua, pātaka, pou whakarae, and chiefs’ house. Ellis uses the socio religious, sociopolitical, and sociocultural milieu of the East Coast at the time to illustrate the shifts and changes in architectural structure, carved form, and visual embellishment. The period 1830 to 1930 represents a massive development in Māori art. The book highlights a period of experimentation, innovation, and unprecedented need for change, while at the same time setting in place the markers of tradition. Ellis goes to considerable length to explain that the artists of East Coast carving were agents of change who in fact, at the same time, contributed to an ever developing tradition. Moreover, the book is a tribute to the six extraordinary artists who made up the famous Iwirākau School of carving: Te Kihirini, Taahu, Ngatoto, Pakerau, Ngakaho and Ngatai.

While the book will be of interest to the scholar of Māori meeting house art, it will also appeal to those with an interest in this period of Māori history and those looking to trace their whakapapa links to the East Coast and Ngāti Porou through art. Of interest to Southerners will be the account of one of the pivotal meeting houses that exemplifies the Iwirākau style – Hau Te Ana Nui o Tangaroa was commissioned for the Canterbury Museum in 1874. The current status of this house, lying in the basement of the museum, may be of more than passing interest to both Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Porou.

Ross Hemera (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha) is an established artist and designer whose practice honours and reflects the cultural and artistic traditions of his iwi. He has undertaken several significant public commissions, including the Whakamārama sculpture at the entrance to the Māori section of Te Papa Tongarewa the Museum of New Zealand, and the “Tuhituhi Whenua” mural at Te Hononga: Christchurch Civic Building.

Ross Hemera (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Māmoe, Waitaha) is an established artist and designer whose practice honours and reflects the cultural and artistic traditions of his iwi. He has undertaken several significant public commissions, including the Whakamārama sculpture at the entrance to the Māori section of Te Papa Tongarewa the Museum of New Zealand, and the “Tuhituhi Whenua” mural at Te Hononga: Christchurch Civic Building.

The Struggle for Māori Fishing Rights: Te Ika A Māori

Nā Brian Bargh

Huia Publishers

RRP: $45.00

Review nā Craig Ellison

Fisheries settlement is told – and this book from Brian Bargh released at the Māori Fisheries Conference in Auckland this year is a book to start to tell this most important story.

Fisheries settlement is told – and this book from Brian Bargh released at the Māori Fisheries Conference in Auckland this year is a book to start to tell this most important story.

The book outlines the struggle – from the early days, almost immediately after the signing of the Treaty, through to the recent tensions around aquaculture development and foreign charter vessels operating in New Zealand waters.

Given such a breadth of time – and at just over 200 pages – it can only be a teaser for what has been a lengthy and difficult process. The story is based on interviews with and recollections from those involved, and the reports from the courts and Waitangi Tribunal, as well as media reports and previous publications that have contributed to parts of the tale.

The central tenet is that this Settlement rests on four pou:

• The indomitable will for Māori to survive as a people and a culture

• The Treaty of Waitangi

• The findings of the Waitangi Tribunal – particularly the reports on Manukau, Muriwhenua, and the Ngāi Tahu Fisheries Report

• The findings of the courts – up to and including the Privy Council.

The book details the process that led to the first or Interim Settlement in 1989 and the more substantive Settlement in 1992. The events following the signing of the Treaty are touched on and establish a strong sense of continual disappointment in the failure of the Crown to adhere to what Māori believed was encapsulated in Article Two.

Critical events are seen as the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal and the fisheries reports it released, and the acceptance by Pākehā judges and political leaders that an opportunity to correct significant wrongs should be grasped. Interestingly it also notes the widespread opposition within Māori to the form of the final settlement, even though they have become fervent participants and supporters of its fruits.

Spread throughout the book are numerous recollections from those involved – from our own Tā Tipene, to those no longer with us – Tā Robert Mahuta and Matiu Rata. Passion and perseverance shine through – as well as great personal fortitude to confront not only the established government and industry, but also widespread criticism from within Māori.

The sequence of events leading to the 1992 Settlement – the so-called Sealord Deal – are explained with a mix of recollection and reaction. The interaction with the fishing industry of the time is not well explored, and sadly a number of the initiatives from industry for resolution are ignored, while the more extreme reactions are covered.

There are some great insights into the raw politics of the time, the need for haste, and the displays of leadership required from all sides to overcome tensions between the negotiators, and to persuade the caucus of the value of this settlement.

Indeed, there is much detail regarding the reactions of iwi in hui throughout the country attempting to secure support for the “deal”. It is interesting to note the passions of the time versus the positions of today!

The book then moves onto considering the tumultuous events around the Foreshore and Seabed – starting with the Tribunal report, passing through the Clark governments’ introduction of legislation to block Māori ownership interests, and the creation of the Māori Party and its successful action to repeal the Act. Nonetheless, the victory is defined as “partial” – probably fairly as well, since there has been little further development in this area.

How Māori continue to develop in the sector is left open, but the current state of Māori influence or control in the fishing sector is seen to be significant. Pākehā fears have been laid to rest with the changes brought about by Māori being accepted by participants and owners.

It is interesting to read of the many claims against the Crown by early objectors, which are being mirrored by current anger over recent decisions around the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary. It would seem that although the current industry accepts the advance of Māori in the sector, the Crown still seems forgetful at times of their obligations under the settlements outlined in this book.

This study is a good summary of the process, tall tales, and anguish that are part of the fight for Māori fishing rights. It does, however reflect the views of a few, rather than a wider sampling of those involved.

Craig Ellison (Ngāi Tahu) is the Executive Chair of Ngāi Tahu Seafood. He has a long history in the fishing industry and was involved in the introduction of the Quota Management System, and from 1992–2004 was a Te Ohu Kaimoana (Treaty of Waitangi Fisheries Commission) commissioner.

Craig Ellison (Ngāi Tahu) is the Executive Chair of Ngāi Tahu Seafood. He has a long history in the fishing industry and was involved in the introduction of the Quota Management System, and from 1992–2004 was a Te Ohu Kaimoana (Treaty of Waitangi Fisheries Commission) commissioner.

Ka Ngaro te Reo – Māori language under siege in the 19th century

Nā Paul Moon

Otago University Press

RRP: $39.95

Review nā Hana O’Regan

It’s important for any book that is endeavouring to document a historical narrative to help the reader to embark on a journey through the history at hand. Like any journey, it needs to flow in a way that the path is easy to follow, and although there may be the odd detour and shortcut, they are still able to move through and navigate the narrative in a consistent direction and with their general bearings intact at all times. Quite simply, the journey needs to make sense. A historical journey needs to carefully consider the landmarks of significance in time that require acknowledgement, as these will give context to the journey itself. These monuments of experience and time will help the reader to locate themselves in the narrative so they understand the relationship between the path already travelled, and its connection to the path ahead.

This is not to say that the journey is always a pleasant one. At times you may come across scenes that disturb or revolt you, images and situations that make your blood boil and challenge your desire to continue. At these junctures, there needs to be enough of the story that engages you emotionally and intellectually to make you want to get to the end destination. This book, Ka Ngaro te Reo, does just that. For a reader like myself, who has a profound affection for te reo Māori, there are parts of this journey through the history of the language that were an affront to my senses of justice and tikaka, and left me feeling angered and saddened at the experiences that our treasured language had to endure.

Throughout Ka Ngaro te Reo, Moon lets the words speak for themselves with numerous direct quotes that leave no room for doubt as to the intentions, persuasions, and agendas of the waves of attack on te reo. Yet throughout this narrative, there was a current of persistence and resilience that seemed to weave its way through the decades of the 19th century. The current at times would seem to disappear into deep pools of linguicide where the language was committed to a certain death. And yet, at every corner of the journey through the decades, the persistent current of resistance and determination for the language to persist and find a way to exist emerges from the pools, and forges a new channel of protest and fight.

At times it is a trickle – at times a creek that quickly turns into a torrent and succeeds in cutting new paths across the land. In this way, Moon provides the narrative, a current of hope for the language that can help lift the reader from the overwhelming sense of hopelessness that comes with the obstacles that the language has faced, to a position of possibility. Just the fact that the language has managed to survive through the century of war upon it gives hope.

For those of us who are familiar with efforts to keep our language alive and thriving in the 21st century, this is an important read, albeit an emotionally difficult one at times. For those neutral or opposed to te reo revitalisation, Ka Ngaro te Reo will at the very least dispel some myths about our history and linguistic colonisation. I look forward to the next instalment that leads readers on the next part of the journey of our Māori language.

Hana O’Regan (Ngāi Tahu – Kāti Rakiāmoa, Kāti Ruahikihiki, Kāi Tūāhuriri, Kāti Waewae) is the General Manager, Oranga at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Previously she was the Kaiārahi – Director of Māori and Pasifika, and the Director of the Student Services Division at Ara Institute of Canterbury.

Hana O’Regan (Ngāi Tahu – Kāti Rakiāmoa, Kāti Ruahikihiki, Kāi Tūāhuriri, Kāti Waewae) is the General Manager, Oranga at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Previously she was the Kaiārahi – Director of Māori and Pasifika, and the Director of the Student Services Division at Ara Institute of Canterbury.

Christchurch Ruptures

Nā Katie Pickles

Bridget Williams Books

RRP: $14.99

Review nā Diane Turner

This book is another from the BWB Texts series, promoted as being “short books on big subjects”, and is designed to be a “platform for discussion, ideas, and critical analysis”.

This book is another from the BWB Texts series, promoted as being “short books on big subjects”, and is designed to be a “platform for discussion, ideas, and critical analysis”.

Katie Pickles is a Professor of History at the University of Canterbury, and is the current President of the New Zealand Historical Association.

The “Ruptures” are of course the Canterbury earthquake events. The notion is that these events caused a rethinking of the past to make sense of the present and to be able to imagine the future. The author examines this proposition under the themes of landscape, people, heritage, culture and politics.

It is not surprising that a large part of the book examines Christchurch’s colonial past, the contribution of early settlers and politicians, the Cathedral, and for me, too much on the sensational 1954 murder of Honorah Parker. Pickles also exposes readers to Ngāi Tahu history and aspirations, and the opportunity that the “ruptures” provide to “ponder past heritage and imagine a just and inclusive future that moves beyond solitude and separate identities” (page 64).

The book makes some interesting observations including that the colonials ignored the landscape at their peril in setting up the city. It also debunks the myth that the earthquakes alone and the subsequent demolitions are responsible for destroying the colonial heritage: “…amidst the nostalgia for post-quake heritage, there was a glossing over of the reality that the city had been knocking down its heritage buildings for a long time” (page 24).

As a person with a very deep interest in the impacts of disasters on communities, this book provides some thought-provoking insights into what the city may become. Ngāi Tahu whānau should remain optimistic that the dream of Maruhaeremuri Stirling, expressed on page 57, may become a reality: “When I walk through the city I wish to see my Ngāi Tahu heritage reflected in the landscape. Our special indigenous plants that we use for scents, weaving, food, and medicine are something unique that we can all celebrate.”

Diane Turner is the Principal Advisor Recovery within the Office of Te Rūnanga. She previously spent two years with the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) as the Deputy Chief Executive Recovery Strategy, Planning and Policy. Before moving to Christchurch in 2011 Diane was the Chief Executive of the Whakatāne District Council.

Diane Turner is the Principal Advisor Recovery within the Office of Te Rūnanga. She previously spent two years with the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) as the Deputy Chief Executive Recovery Strategy, Planning and Policy. Before moving to Christchurch in 2011 Diane was the Chief Executive of the Whakatāne District Council.

A Māori Reference Grammar

Nā Ray Harlow

Huia Publishers, 2015 (First published by Pearson Education in 2001).

RRP: $45.00

Review nā Lynne-Harata Te Aika

E te Toihuarewa kā mihi! I had the privilege of being a student many years ago in Professor Ray Harlow’s Māori grammar course at the University of Waikato. He had a knack of making the most complex grammar seem so surprisingly simple in te reo Māori (to me anyway). We learned grammatical terms applicable in English to any language, but with te reo Māori as the context of learning.

E te Toihuarewa kā mihi! I had the privilege of being a student many years ago in Professor Ray Harlow’s Māori grammar course at the University of Waikato. He had a knack of making the most complex grammar seem so surprisingly simple in te reo Māori (to me anyway). We learned grammatical terms applicable in English to any language, but with te reo Māori as the context of learning.

He sets out a coherent and progressive model for the description of Māori sentence structure. He also familiarises readers with some of the concepts and terminology used in describing language structures. Additionally, he provides some answers to questions that readers will have about individual constructions.

This book is a useful text for advanced te reo Māori teachers and students. It also demonstrates the valuable contribution Ray Harlow has made to te reo Māori from his early days in Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori to his academic career in linguistics at the universities of Otago and Waikato.

Lynne Harata Te Aika (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Awa) is the General Manager Te Taumatua at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. She is the former Head of School for Māori & Indigenous Studies in the College of Arts at the University of Canterbury, and the former Head of School – Māori, Social & Cultural Studies, at the College of Education.

Lynne Harata Te Aika (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Awa) is the General Manager Te Taumatua at Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. She is the former Head of School for Māori & Indigenous Studies in the College of Arts at the University of Canterbury, and the former Head of School – Māori, Social & Cultural Studies, at the College of Education.

Opinions expressed in REVIEWS are those of the writers and are not necessarily endorsed by Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.