Volume 1: Te Tīmatanga o Te Kerēme WAI 27, lodged by Henare Rakiihia (Rik) Tau

Oct 5, 2017

Ngāi Tahu Claim Processes Wai 27: How I became the claimant, and how I established the Ngāi Tahu “A-Team” that presented the evidence to the Waitangi Tribunal.

Nā Rik Tau

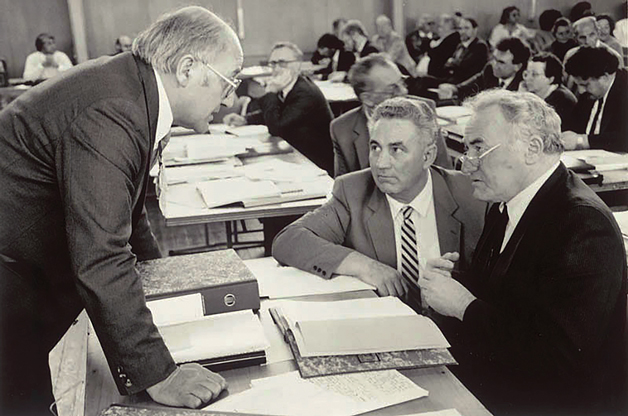

Members of the Ngāi Tahu Negotiation ‘A-Team’: Back Row (left to right): Kuao Langsbury, Trevor Howse, Edward Ellison. Front Row (left to right): Tā Tipene O’Regan, Charlie Crofts, Henare Rakiihia Tau.

Notification

Stephen O’Regan then Maurice Pohio phoned me, stating that as Chair and Deputy of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board they had resolved to ask me to be the person to lodge the Ngāi Tahu Claim under the Treaty of Waitangi Act for breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi that prejudicially affected Māori. This was in May 1986. O’Regan was working for the Conservation Department at the time, so that had eliminated him from being a claimant. I accepted. I was very familiar with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi and the history of broken promises made by the Crown to our ancestors. I grew up with the Crown’s dishonesty to the Treaty of Waitangi. My parents were members of the Hāhi Rātana, and so were all my uncles, aunties, and the leaders of our hapū,

Ngāi Tūāhuriri. My pōua had fought to have the Kemp’s Deed of Purchase recognised, and an outcome of that was the establishment of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board.

I immediately phoned my uncle Pani Manawatu, who was an Āpotoro of our church, and the Upoko of Ngāi Tūāhuriri.

I was an ākonga of our Hāhi, and very familiar with the whakapapa of our history. Our Hāhi was built upon two pillars, or pou. Those pou were the Paipera Tapu and the Treaty of Waitangi. Our whakapono was simple: Whakapono i te Matua, kotahi, te Tama kotahi te Wairua tapu kotahi me ngā Anahera pono me te māngai Āe. The importance of what they represented in te Ture Wairua and te Ture Tangata was always clear.

Inoi

I spent two hours in prayer, seeking strength and protection for the challenges before me as I would be walking with the ancestors. I would need spiritual and whānau support. Tests of trials and tribulations would be many, but the greatest strength for me would be my own whakapono. I had my own whānau support – brothers, sisters, cousins, and sons, in particular Te Maire. He was studying our history of the South Island Māori at the University of Canterbury, which incidentally was the doorway to trained researchers. Whakamoemiti would always be before me in all things.

My media release was for an impending claim to be lodged on behalf of Ngāi Tahu whānui. It was of national interest, as our takiwā spread over half of the land mass of New Zealand. Many European organisations wanted to know what we were claiming, and whether our claim would affect their property rights. This commenced a continuous round of public meetings for the next three years explaining very clearly with my public utterances that we were not claiming privately-owned land held by individuals, as our claim was not to create further injustices by righting past injustices. Only the Government could right the wrong, as they held or claimed ownership of all the family jewels of New Zealand.

Lodging the Statement of Claim

I officially lodged the claim with the Waitangi Tribunal during the tangi of our Deputy Upoko, Poia Manahi, who was also the Āpotoro Takiwā of Te Waipounamu. I discussed the words for our claim with my relation Kūkupa Tirikātene while attending the tangi. Hence the Statement of Claim begins with a prayer: E Ngā Mana E Ngā Kārangaranga O Ngā Herenga Waka Katoa Tēnā Koutou I Raro I Te Maru O Te Matua Tama Wairua Tapu Me Nga Anahera Pono… Then [solicitor for Ngāi Tahu] Mike Knowles wrote up the Statement of Claim, and faxed it to me for my signature. This always took place for me after 3 am, – the time I was getting home from the tangi to do these things before returning back to the marae at 7 am to be on the paepae. People from all over the North Island as well from the Chatham Islands and South Island all came. I asked one of our Āpotoro, Mano White, to pray for the Statement of Claim and myself. This he did, and that day our senior Āpotoro of our Hāhi buried Poia Manahi in the Urupā Kai a te Atua. That was on, I think, 1 September 1986; although the Statement of Claim is dated 26 August. When they left this marae to go to the Urupā Kai a Te Atua, I took the signed Statement of Claim to Sidney Boyd Ashton, the secretary of the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board, for him to give to Mike Knowles. I then drove home. The next thing I remembered was that I was in the country, and I noticed our Reserve Torotoroa. I was in Leithfield. So I returned to the marae, and sat down on the paepae to wait, as the whānau pani had not returned home from the urupā. I went to sleep and when I woke, everything was over. So I said to the whānau, I will go to the hotel and have a drink. When I arrived at the hotel a phone call came for me, telling me that Pōua Jim Tau had died. I arranged to go with the whānau to take the body of our whanaunga to the marae at Rāpaki, and to also take the wife of Poia Manahi with us; all arranged for 2 pm the next day. I slept soundly that night, as well the next three nights at the tangi of our whanaunga. I had to travel to Wellington on the day of his tangi; that was a Friday. By then I had fully recuperated for the tasks in Wellington.

In September 1986 … the Tom Te Weehi judgment was released by the High Court. It found that our customary rights were protected in law, as Tom Te Weehi was found not guilty of taking pāua from Motunau in excess of fishing regulations that none of us were aware of. I had earlier given him a tuku moana or a customary and Treaty of Waitangi right to take a feed for himself and whānau. I knew we owned the fish and fishery, as our ancestors reserved our mahinga kai in the Kemp’s Deed of Sale and Purchase. Also, they were reserved from sale under Article 2 of the Treaty of Waitangi.

I was a permanent employee at the local meat works of Borthwicks and the CFM Plant in Belfast, working in a very highly-paid position. I knew I could not do the work as the claimant if I was working, so I applied for a year’s dispensation, thinking that would be enough time to present our case and return back into paid employment. That was what I thought would be my contribution as the first claimant, and it was my first miscalculation. The evidence and hearings for our claim took four years. So I was paid off after the one year, and I received my superannuation contributions, which came in handy for paying bills. At that time I only had historian Harry Evison with the necessary research skills, and I knew I would have to build up a team around me, which was my priority. I immediately needed people from Tuahiwi with me. I first phoned my relation Jimo Te Aika, then Aunty Rima Bell to be a kaikaranga for me, and asked them to join me with the claim. Nō te mea ko te hōnore te pono me te whakaaro pai, tētahi ki tētahi ngā kai here kai hono, te whakaaro kei roto i te Tiriti o Waitangi. I was drawing on the relationships of my teachings within our Hāhi. Many more were to follow.

Trevor Howse was a volunteer at that time, working with me as secretary of our rūnanga on Māori land tenure and the difficulties that Māori land and we as owners were faced with. I noticed he was attending all the meetings requested of me. I asked him why was he not at work. He said to me, “How can I support you if I am at work? I have handed in my notice to help out.” Wide-ranging offers of help were continually coming from members of the wider Ngāi Tahu whānau offering to support the tasks to right the wrongs imposed upon our ancestors. This created a dilemma. I was not in paid employment and neither was Trevor. It was wrong to have two of us unemployed doing the work for the claim. Behind the scenes, I asked our secretary to put Trevor on a wage if possible, and also requested this from my fellow board members. They agreed, so Trevor was employed. It made me think about the people who would be required to assist us in our research and help pay the costs. Miracles do happen, and they were well documented in our church.

Rik at Tuahiwi, 3 December 1989.

As an example of my strategy, I approached our retired county clerk Hamish McKenzie to assist me. I wanted him to research all the Māori land records for information relevant to our lands. He asked me, “What can you pay me, Rik?” I said, “Ten cents an hour more than I.” He said “How much is that, Rik?”, and I said, “Ten cents an hour.” So he said, “Well, how about giving me petrol money for travel?” I put that request to our secretary, which he accepted.

How to pay for the claim expenses for employing lawyers and experts was continually on my mind. What I and my team thought was a possible miracle occurred in September 1986, when the Tom Te Weehi judgment was released by the High Court. It found that our customary rights were protected in law, as Tom Te Weehi was found not guilty of taking pāua from Motunau in excess of fishing regulations that none of us were aware of. I had earlier given him a tuku moana or a customary and Treaty of Waitangi right to take a feed for himself and whānau. I knew we owned the fish and fishery, as our ancestors reserved our mahinga kai in the Kemp’s Deed of Sale and Purchase. Also, they were reserved from sale under Article 2 of the Treaty of Waitangi.

High Court Judgment on Tom Te Weehi, and how to pay for legal costs

From reading the judgment of the Tom Te Weehi case, I identified the positives and also the negatives. I immediately convened a meeting at Rāpaki to protect our mana tuku iho, our heritage rights reserved from sale in the words mahinga kai which were rights and not privileges that belonged to certain members of Ngāi Tahu only. I was an owner in all those mahinga kai reserves the Crown granted, so I had no intention of letting anyone steal what was reserved for us, let alone what our tūpuna wanted reserved and were denied in a breach of the Treaty of Waitangi. From that judgment I had invited representatives of the (then) Ministry of Fisheries (MFish). I welcomed, they replied, and then I told them that in view of the Tom Te Weehi case, we as Ngāi Tahu whānui needed to make some decisions first to protect our fishing rights before they could speak. This could only be done by placing a rāhui over the whole of our coastline from, I think, the Hurunui to Ashburton, until we could convene a meeting with representatives of all of our marae within the takiwā of Ngāi Tahu. This was adopted as an interim measure to allow us to sort out the web around ownership that MFish had created with our fisheries. Once we had agreed to this, then we could deal with MFish in due time. That judgment had the possibility that our ownership rights could be interpreted to be a Māori right, rather than a tūrangawaewae or mana whenua right to identified and legitimate owners. Hence the rāhui first.

Fishing assets

Our conclusions from the Tom Te Weehi case and strategies were determined by our small team, which consisted of Trevor Howse, Jimo Te Aika, and Peter Ruka. Our strategy was that we would use our customary rights as per the Tom Te Weehi case, and fish for orange roughy, a highly-priced fish, selling them in Fiji where [General Sitiveni] Rabuka had seized control to protect their Aboriginal rights – whanaungatanga. We had the support of all people who were flocking to us, Ngāi Tahu fishers, etc. Support existed from the meetings we were having upon the Ngāi Tahu marae, as well as support from Jim Elkington and his uncle Rangi from Te Tau Ihu o te Waka. Also, many of our kaumātua were in favour of this method of paying the bills that were before us. But when we got back home to our marae here in Tuahiwi, our people looked at it differently. They saw me as the claimant for the whole of Ngāi Tahu whānui, and the need to protect me and my status as the claimant first. They requested that we get a legal opinion so that I as the claimant would not find myself in trouble and possibly jailed before we had commenced the hearings before the Waitangi Tribunal.

I asked Mike Knowles for his legal expertise on our proposal. His reply was not what we wanted to hear, so we thought to seek another opinion. Among our discussions the name David Palmer came up as a top-line lawyer. I said I knew him, and Pura Parata also recommended him. I made contact with him for an appointment. On the due date, Trevor Howse, Jimo Te Aika, and I walked across to Weston Ward & Lascelles to state our case to David Palmer. I took with me the details of Kemp’s Purchase reserving our fishery and mahinga kai resources; told him what mahinga kai really meant, and that was not plantations as the Pākehā stated; and also showed him the Tom te Weehi judgment. I also said that I was to go to the Muriwhenua fisheries claims before the Waitangi Tribunal in Kaitaia to give them support in their hearing. David said he would read the information and tell us where we stood in a week’s time. This extended out to another week, and then we went to see him. He told us to “Sit down, shut up, and listen.” That got me into a defensive position straight away, but we sat and listened for almost two hours of lecturing as if we were naughty boys. In brief, he told us we were to be seen as leaders, not radicals. He never to my recollection stated it was an illegal act. He said he would write up a statement for us to take to Kaitaia in the Muriwhenua fisheries claim before the Waitangi Tribunal. I replied by saying very little but I got to the heart of the issue and with dignity and with tongue in cheek I said, “Thank you very much for your advice and for your offer of assistance. You are now employed to represent us and your cheque for payment is on the same boat as our fish.” I told Sidney Boyd Ashton and our board members, and hence David became the full-time lawyer representing us. Our secretary had to find funds for David’s expertise, and during the Claim period, we would find that expertise to be tremendous.

Our team was getting larger. At this point we had Michael Knowles and David Palmer as lawyers, with Harry Evison as a historian, and the possibility of my son Te Maire. Kuku Karaitiana, who worked for the Justice Department in Wellington, was able to inform us on what we had to do to comply with Government policies.

Building the team

I met Paul Temm QC for the first time as one of our lawyers at a conference convened by the Waitangi Tribunal in Wellington. We were there to discuss the hearing protocols for all parties presenting evidence to the Waitangi Tribunal upon our marae at Tuahiwi. David Palmer attended with me. Paul Temm stood up before the Tribunal and started to tell them how our kawa would be operating on our marae. I had only met him about 20 minutes before, so you can imagine what I was thinking about this self-appointed Pākehā mouthpiece of our marae when he had never been to it and I did not know him. I stood up and made it quite clear to all present that Paul Temm had no speaking rights or authority to speak for our marae, that I was the person who shall make all those decisions. I received many reports from staff members of the many Government departments that left me suspicious of Paul.

From left: Tā Tipene O’Regan, Trevor Howse and Paul Temm QC.

Dr Maarire Goodall, as the Director of the Waitangi Tribunal had to implement the tikanga o te Tari Justice. Maarire said that to hold a meeting on a marae, the Waitangi Tribunal must have the authority to determine the rules of such a hearing or words to that effect, so the marae must give the Waitangi Tribunal mana over the marae. Well, this caused immediate problems to me and to our tikanga and kawa. However, I remembered discussions we had within the māramatanga of our Hāhi and the talks with my uncle and Upoko Pani Manawatu. Nā te Pō tutiro atu ki te Ao Mārama. Only people create problems, not God. The answer became very simple to me when I reminded myself of it, because of all the marae that would buck giving the mana of the marae to the Waitangi Tribunal, it would be us Ngāi Tūāhuriri and our relations at Temuka. This was the tikanga I developed for giving the mana of the marae to the Waitangi Tribunal. Before any opening of the tribunal hearings when they sat on our marae, I would open with whakamoemiti, then at the end I would have a hīmene. During the hīmene I would go to one of the Tribunal members, hongi, and hand to him the mauri of the marae, and it would make the task easier if I gave it to Monita Delamere, who was also Ngāi Tahu, a Tribunal member, and a relation. A miracle happened on the first hearing upon our marae. For reasons unknown to me, the chairman of the Tribunal, Chick McHugh, convened an in-house meeting with Paul Temm. When they adjourned, I saw an opportunity. So I commenced to open the proceedings with whakamoemiti, and during the hymn I went to Monita to hongi, and I said, “Ka hoatu au te mauri o te marae ki a koe.” At the end of a week-long session of hearing evidence, Bishop [Manuhuia] Bennett took the whakamoemiti, and during the hymn Monita would hongi with me and the mauri o te marae was returned. God saved us all.

Sure enough when we got to Temuka for the hearings, their Upoko Jack Reihana tapped me on the shoulder and said, “What’s this about giving the mana of our marae to them?” I explained what I had put in place at Tuahiwi. Like me, Jacko was also a member of the Hāhi Rātana, and so I knew we could not argue against God. So our Hāhi and our beliefs overcame such obstacles. Faith in God overcame the problems, but they had to be addressed and overcome. Such concerns for the little picture drive the big pictures. Any issue of tikanga had to be overcome with good reason and compassion.

Somehow we had to identify all lands within the takiwā of Ngāi Tahu by the end of the following day, the deadline set by Government, and we had to register them with the Waitangi Tribunal. Emails identifying Crown-owned lands in our takiwā were received by us between the hours of 11 am and 4 pm on that day. Trevor Howse was booked on a flight to Wellington to deliver these records to Dr Maarire Goodall of the Waitangi Tribunal. I think Maarire and Trevor finished stamping receipt of the letters at 11 pm, which met the deadlines set by Government. This prevented the Crown from disposing of the Crown’s properties.

The State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986

Stephen O’Regan came down to inform us about the process that was required for us to prevent the Crown’s land assets from being sold in the privatisation policies of the then Labour Government. Somehow we had to identify all lands within the takiwā of Ngāi Tahu by the end of the following day, the deadline set by Government, and we had to register them with the Waitangi Tribunal. Fortunately I knew the local staff of the Department of Lands and Survey, so I asked Peter Ruka and Trevor Howse to go across and make an urgent appointment for me at either 8 or 9 am the next day. I met one of their decision-makers the next day at 9 am. I put the statutory requirement as required by Government to them and they agreed to comply. They said to organise all the fax machines in a certain place not far from their offices in Cathedral Square, and they would have their offices around the South Island email them to that office and they would fax them. All of their emails identifying Crown-owned lands in our takiwā were received by us between the hours of 11 am and 4 pm on that day, filling up several boxes. Trevor Howse was booked on a flight to Wellington to deliver these records to Dr Maarire Goodall of the Waitangi Tribunal. I think Maarire and Trevor finished stamping receipt of the letters at 11 pm, which met the deadlines set by Government. This prevented the Crown from disposing of the Crown’s properties. It does sound similar to the sale of shares in the current SOE sale of water power generation companies. We ensured that the Crown of that era had resources to be used as a settlement with us when our hearings were completed and the Tribunal had written up its report and recommendations. I asked all marae to facilitate discussions to identify lands in their takiwā from these surplus Crown lands that the Crown desired to sell and could be used in a settlement. We would eventually land bank them.

Land bank for Ngāi Tahu

Arising from this process, David Palmer observed that the Christchurch Polytechnic had advertised that they were selling off lands. David put an injunction in and notified the Crown of our action, as the sale was contrary to why we identified all Crown lands –

to prevent the Crown from selling them off. This action created what was then a process in which if the Crown desired to sell property then they had to notify us through the Trust Board. If we desired to retain such lands, we would notify the Crown and say, “Hold it for use in a settlement.” This single step created what was called the Land Recovery Kōmiti, of which I was chair, and once again we were all volunteers. The agreement reached with government allowed us to land bank assets up to $40m. This continued after the Waitangi Tribunal hearings into the negotiations process that started in 1991.

Public Relations

We needed to be able to communicate with the people in the South Island. My relationships with the Department of Internal Affairs, which dated back to the early 1970s, came into play. I was assisting Garry Moore, Wally Stone, and many staff members; and so they started to come to our Friday night weekly discussions. They saw the need to assist, so funding was provided by the Department to employ a writer so that we could circulate information to all of our marae and community organisations. We employed Shona Hickey to be our writer and called that newsletter TE KARERE.

Bill Gillies from Rāpaki, who worked for the Education Department, attended our small team’s strategy meetings when he could. He was friends with journalist and media personality Brian Priestley, as well as David Palmer. The need existed for training us in media realities. So Brian attended our meetings as a volunteer, and advised us on how to address the media and prevent them from printing wrong messages. It was preferable if we could have a one-stop shop media person. David Palmer then had a meeting with The Press (Christchurch) editors, and the outcome was that they attached Jane England to us as their reporter. This was another miracle, as we needed only to talk to her. It did not always happen that way, but we discussed our strategies and public relations obligations with Jane, and that removed a lot of racial media reporting, guesswork and speculation by outside media personnel. Jane attended our strategy meetings and was treated as a member of our family.

Okains Bay’s important part in our hearings protests

We opened the proceedings to commemorate Waitangi Day at Okains Bay in about 1973. This was a leadership move determined by Murray Thacker, Hori Brennan, and Tip Manihera; and supported by our Upoko Uncle Barney, Poia Manahi, and myself as secretary of the rūnanga. This was a first in New Zealand. The year prior to that, as a Meat Worker and union advocate, I, alongside a colleague, advocated that our workers recognise the meaning of Waitangi Day and take time out on that day to study the history of it. This was agreed by resolution, so we had for the first time in New Zealand local workers taking an unpaid holiday in Canterbury to commemorate the Treaty of Waitangi. So when we had Waitangi Day commemorations at Okains Bay, we had volunteer workers to assist this small community leading the way in New Zealand to recognise Waitangi Day. It was after this that Waitangi Day became a statutory holiday. So you can see why public comments from me “that there was a better class of citizen in the South Island” were made. So each year some of us would travel over to Okains Bay and welcome the public to the museum marae, address the principles of the Treaty, paddle the waka, and participate in activities designed to commemorate the Treaty of Waitangi and fundraise for the Okains Bay Museum.

Rik with Bob Whaitiri at the Tribunal Hearings, Te Rau Aroha, Awarua February 1988.

However, protests started in and around the 1980s, with people stating clearly that New Zealand was Māori land and that the Treaty of Waitangi was a FRAUD. In 1986, some protesters cut some fences over there. In 1987 I sent word out to them that I wanted to see them on the marae and discuss the Treaty of Waitangi with them. So after the official pōwhiri to the Governor General’s representative and replies, we had another pōwhiri to the protesters. Most of the protesters were non-Māori. They heard what I said, then they replied. We listened to them. Stephen O’Regan was present. He said to me, “I will reply to the Māori spokesperson, a descendant of Wahawaha.” So with an effective response O’Regan dealt with the human frailties of the Tupuna Wahawaha, which quieted them all. Then I spoke about our claim seeking justice where justice was due, educating the wider public about the Treaty so that it will speak for us all, and it will come from the hearts of the people, which was a proverb of our Hāhi to the Treaty. I spoke about my history lessons at secondary school where our history teacher explained the history of New Zealand by reading out the three principles of the Treaty and then saying; “There is much we have to be ashamed about; the less said the better.” That was it. The colonisation of New Zealand in about two minutes. Hence I was aware that the Treaty of Waitangi was unknown among the Pākehā population – therefore there was a need for a lot of education.

I informed them that we were on the same side, but our approach was different. I remembered David Palmer’s lecture, so I said we must provide leadership with our claim, hence we shall always act with dignity, grace, and charm in proving our case, identifying where breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi occurred. The organisers of the protests were from a structure called Project Waitangi, many of whom I knew. I asked them to join forces and assist us with our claim against the Crown. They agreed, and they gave us Jim McAloon, the son of a judge. Jim had long hair, a long beard, and always wore shorts that had holes in them. He looked like a penniless person. He was a researcher and historian. Well, most of us understood poverty, but Jim was to prove his value, as he was, like Harry Evison, a very competent worker, and a person who sought justice where justice was due and believed in the principles of human rights, and giving a person a fair go in life. So Jim McAloon came to work for us. We eventually found some funding to assist him in his work. But Project Waitangi paid him an amount initially, so I was able to get some funding for his position from the Internal Affairs Department, which I had assisted as a volunteer in their many endeavours. They would prove to be a blessing from heaven to us as well.

Immediately after lodging the Claim I was giving about six talks a week on the Treaty of Waitangi to all interest groups within the many communities of Canterbury. I was always very clear with our policies that the claim I lodged would not affect privately-owned property rights. Our claim was against the Crown, and we did not support remedying injustices against us by placing an injustice upon fellow innocent citizens.

The other coup in the building of our team was finding Ann Parsonson and Barry Brailsford. Both were senior lecturers of history, Barry at the Teachers’ College and Ann at the University of Canterbury. Also, both were lecturers of my son, Te Maire. I was asked to go to the Chatham Islands to inform the people there of our claim and to look at their history. I went, listened, and advised them. The first thing I said was to look at their whakapapa, and I informed them of an 1844 census that took place identifying all living

Ngāi Tahu. The reason I said that was because I was fully aware of the invasion of the Chatham Island by Te Āti Awa, but in any island that is small and isolated, intermarriage is the norm and it runs rife. I said to them, learn these things as you will find out that you all descend from the eaters and eaten; the same as all Māori tracing their descent to their respective waka. To do that would assist them in overcoming divisions. Another of their take was that the Treaty of Waitangi did not apply to them. I said I think it would, because you come under the New Zealand constitution. On my return I contacted Ann Parsonson and asked her to write up a paper for me to send across to the Chatham Island people, identifying for us all whether or not the Treaty of Waitangi applied to them. She did that task for me voluntarily, and I then invited her to be a part of our local Ngāi Tahu team that would assist us with evidence before the Waitangi Tribunal. By this time, David Palmer became the conductor of our team, and was able to discuss with Sidney Ashton the importance of such people. Ann’s father was also a historian, and in times to come the Crown would employ him to represent the Crown, opposing his daughter giving evidence for us in the Ōtākou Deed of Purchase.

I also spoke to Barry Brailsford, and he agreed to assist us. By March 1987 we had a powerful team of orators. Immediately after lodging the Claim I was giving about six talks a week on the Treaty of Waitangi to all interest groups within the many communities of Canterbury. I had Harry Evison and David Palmer assisting from the early beginnings, then Jim McAloon and Ann Parsonson joined us in the many requests to explain what the Ngāi Tahu claim meant and whether it would affect their property rights.

I was always very clear with our policies that the claim I lodged would not affect privately-owned property rights. Our claim was against the Crown, and we did not support remedying injustices against us by placing an injustice upon fellow innocent citizens. This policy was damaged by Stephen O’Regan in his media debate with Robert Muldoon when O’Regan said that our claim would affect private property rights. He was incorrect, and his statement backfired. So our A-Team than had to repair the false and divisive statements made by O’Regan in that interview, among the many community groups that were supporting our claim seeking justice where justice was due.

Waitangi Tribunal and pōwhiri

Before the commencement of the Waitangi Tribunal Hearings upon our marae, I spoke to one of our team members, Jim McAloon. Jim never dressed for occasions – I never, ever saw him wearing a tie.

So I said to him, “For our opening, Jim, I would like you to wear a tie and jacket. Do you have one, Jim?” He said, “Yes Rik, I will put on a tie and wear a jacket.” True to his word, on the day he came up to me dressed with a tie and jacket and said to me, holding his red tie with a smile, “Alright, Rik?”. I said “Pai rawa atu” and smiled back, saying, “I know what the red tie signifies.” We laughed as we were both happy.

By the time the first hearing had been set, four amending claim statements had already been made to the Waitangi Tribunal by our solicitor David Palmer. The hearing date was set for 17 August 1987, more than a year after I officially lodged the Ngāi Tahu Claim. By then I had to give up my job at the Meat Works.

Rik with Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan at Ōnuku for the Crown Apology 1998.

I had arranged with the Director of the Waitangi Tribunal, Dr Maarire Goodall, that the pōwhiri would take place upon the Tuahiwi Marae and then we would have kai before going to Rangiora High School at 1 pm for the hearing, as our whare Maahunui would not be big enough to hold all the Ngāi Tahu people who would be there at the opening of our case, as well as the Crown representatives and the media. We expected 400 to 500 Ngāi Tahu would come, and that was an accurate estimate. When the Tribunal and the Crown representatives arrived and parked outside the marae gates, many Māori also arrived. We were ready and confident in ourselves that we could handle most challenges. When it appeared that the manuhiri were ready, the karanga came from our mahau and the replies in return. As per our custom, we opened all proceedings with karakia to whakawātea and whakanoa our hui. We had three speakers I think: Bob Whaitiri, Stephen O’Regan, and I concluded. The manuhiri replied. I cannot remember who the Tribunal speakers were, but somewhere in the mix, speakers from Te Tau Ihu o te Waka stood up and spoke. A Rangitāne speaker stood up to oppose our claim and the boundaries to our claim, and laid a koha upon our marae. Stephen O’Regan said to me, “Have you ever seen a koha returned?” I innocently replied, “NO”’. He said, “Would you like to see how it is done?” and I said “OK”. On that, he stood up, picked up the koha, thanked them, placed it before them, and then kicked it to them. Well, once he did that I could hear expressions of concern from behind me from our own people, let alone what was happening on the other side. With dignity, they replied and replaced the koha back. I immediately put my arm in front of O’Regan, and said to my son Te Maire to pick it up. He did, and I sighed a breath of relief. That action surely represented what the marae ātea is, te wahi o Tūmatauenga and the kawa, ka pūrehu te hau. The dust was surely stirred, but we then knew that the dust could also settle on us. What was done could not be undone.

The mihi took quite some time, and it was obvious that we would not make the deadline to officially open proceedings at the Rangiora High School at 1 pm. We had prepared well for feeding all manuhiri, with meals at Rangiora High School during the week. Our head ringawera was Alamein Scholtens, and her team. We had about 200 fresh muttonbirds and 80 salted muttonbirds as a koha from those of us who bird on our island, Pohowaitai. Henry Jacobs, my brother-in-law, said to me quite early in the piece that he would give some lambs to feed our manuhiri. So he and I butchered 10 of his lambs, and cut them up for our ringawera to feed our manuhiri. Hilary Te Aika provided all the vegetables, and I provided many eels as well as flounders. Other people provided support in other ways. My sister always provided the lollies for our hearings. Although the hearings for week one were held at Rangiora High School, we had our Ngāi Tahu people also staying on our marae at Tuahiwi and other manuhiri who came. For example, Matiu Rata and some from Ngāpuhi arrived on the evening of day one or two. Mihi and exchange of information took place as they came to support our claim, reciprocating our visit to Kaitaia to support their case before the Tribunal. So all these activities were occurring during the first week of Tribunal hearings.

Summary

Many more blessings were to come to our local team. For us, the Treaty principle of our Hāhi, Ture Wairua, and Ture Tangata were well established within our local team, which became known as the Ngāi Tahu A-Team. The Treaty and Bible principles were inseparable in my beliefs.