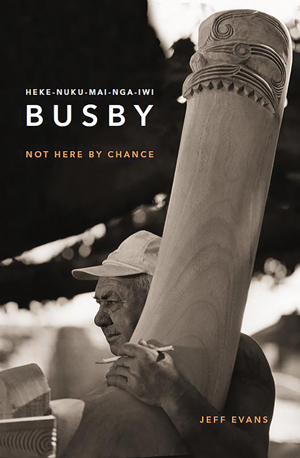

Waka Legend

Oct 6, 2015

Hekenukumai Busby is credited with reviving waka building and celestial navigation in Aotearoa. His waka have sailed between New Zealand, Hawaii, and many islands in the Pacific and he has made at least 30 waka, including several waka hourua (double hulled sailing waka).Understandably, kaituhi Jeff Evans was a little nervous when he first began talking to Hec in a series of conversations that would become a biography, Not Here By Chance.

The first time I drove north to interview Hec Busby at his Aurere property I was nervous. I figured that from the moment I left home I had four hours to prepare myself, but I knew it was never likely to be enough time. I was a writer of modest ability who had published a handful of books covering topics such as Māori war canoes, Māori weaponry, and traditional Polynesian navigation. Hec, on the other hand, had already built several waka taua, was an expert in mau rākau, and had actually guided the voyaging canoe Te Aurere (which he had built) thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean using stars, the moon, and the sun as his compass. What was I thinking?

Still, I tried to reassure myself that there must have been a good reason we had found each other the previous February. Hec (Te Rarawa, Ngāti Kahu) had been busy organising the crew of the great waka taua Ngā Tokimatawhaorua at Waitangi, and I was there to enjoy the spectacle with my family. For one reason or another I got talking to Stanley Conrad (Te Aupōuri) – Te Aurere’s captain – and he in turn introduced me to Hec. It was soon after that brief encounter that

I phoned Hec to ask whether he was interested in sharing his life story with a wider audience.

I’m still not entirely sure where I drew the confidence from to imagine I could write a biography, or why Hec consented, but we both had a strong interest in promoting Māori culture and I knew instinctively that his story needed to be told. And so here I was a few months later, speeding past Mangonui and Coopers Beach and crossing the single bridge at Taipa that would become the silent signal I was nearing Hec’s home. All the while I was readying myself to ask a man I barely knew to open the vault that was his life for me.

I’m still not entirely sure where I drew the confidence from to imagine I could write a biography, or why Hec consented, but we both had a strong interest in promoting Māori culture and I knew instinctively that his story needed to be told. And so here I was a few months later, speeding past Mangonui and Coopers Beach and crossing the single bridge at Taipa that would become the silent signal I was nearing Hec’s home. All the while I was readying myself to ask a man I barely knew to open the vault that was his life for me.

When I finally arrived at his home on that first trip I was greeted warmly and we were soon at work compiling a list of events from his life that we might explore for his biography. Only we didn’t get far. It soon became clear that Hec either wasn’t comfortable talking about himself, or he had been so caught up in the day to day living of his life that he had never taken the time to look back at what he had achieved.

To get us started, I asked some questions about his experience as the kaitiaki of Ngā Tokimatawhaorua, and what had driven him to build Mataatua-Puhi, the first waka taua he had constructed – just a stone’s throw away from where we sat. His daughter-in-law, Gina Harding, then appeared with sheet of paper naming all of the waka he had constructed here since that first one was launched in 1989.

Within the next few years he may also be able to add to his accomplishments the construction of a carving school and the commencement of a whare wānanga, on land near his home that he has donated. It will be here, in the sacred school, that classes on navigation, canoe building, sailing, and other topics will be taught. Despite its relative isolation, this will be a place where people gather, and make things happen.

Writing the biography of such an iconic figure is of course an honour, but an honour that comes with the weight of almost overwhelming responsibility. Simply put, the author needs to get it right. So the question was, exactly how do you get it right for a man who has lived for over 80 years and achieved so much? The late biographer and historian, Michael King, said that when writing about living subjects, the biographer is charged with trying to locate their subject “in their social, cultural and historical context”, as well as doing their best to “shed light on motivation and character, and to identify and evaluate achievement.” King’s guidance gave me clarity and focus, and was a boost to flagging confidence.

Nevertheless, there were tough days when the challenge hung over my head and paralysed my writing. On those days I was often able to ease the pressure by concentrating on background research relating to the Busby whānau itself. They had a long and rich history in and around Pukepoto, a small settlement just outside Kaitaia, and showed up on a surprisingly regular basis when searching online resources such as The National Library’s helpful sites, Papers Past and Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives. For instance, Timoti Puhipi’s failure to gain the Northern Māori electoral seat featured in a report from 1876:

The natives of this district are naturally disappointed that Mr Timoti Puhipi was only second on the list of candidates for the Northern District in the General Assembly. I thought there would have been a case of bribery at elections. It was stated the successful man was returned by the admission of the votes of little boys; but the fact was that some of Mr Puhipi’s own people so much objected to his going from the district that they refrained from voting in numbers which, had they voted, would have placed him at the head of the poll.

Later, when I shared some of these recollections with Hec, he began to open up with his own tales and quickly added the story of the great navigator-ancestor Tūmoana and the arrival of the Tinana waka: it was this ancestor’s return voyage to his Polynesian homeland that had been the inspiration for Te Aurere’s maiden voyage to Rarotonga in 1992. And I heard of Puhipi, Hec’s great-great-grandfather who signed the Treaty of Waitangi in late April of 1840 at Kaitaia, and whose taiaha Hec still had possession of.

Of course I had always been excited to be working with Hec on his book, but it was only as he began to open up and share memories of his own childhood that I finally began to realise the magnitude of the gift I had invited upon myself. Sitting for hours at a stretch while Hec reached back into the depths of his memory was both a rare honour and a humbling experience. His stories describing events that occurred on the Home Front during the Second World War, for example, were mesmerising.

He was there when Pukepoto’s soldiers spent their last evening on Te Rarawa Marae before leaving for war, and he listened as an elder named those who wouldn’t return home. Those named, he learned in later life, were the men, many barely out of their teens, who cried while shaking hands and saying their goodbyes. And once the Māori Battalion had departed our shores, newspaper articles captured the efforts of the community to raise funds so they could send packages of woollen socks and mittens, chocolate, and letters from home for their men fighting on the front line. Hec also remembered marching with his school mates into the hills behind Pukepoto to explore a freshly constructed nīkau village – a temporary refuge should the Japanese attack along Ninety Mile Beach.

On another visit Hec told me stories of long summer days sitting under the shade of a tree as a great-aunt shared stories of Kupe and other ancestors, and how captivated he had been by such traditions. Those memories, along with school trips to Waitangi where the newly built Ngā Tokimatawhaorua lay at rest, would prove to be the sparks that ignited Hec’s lifelong passion for waka.

Like many involved at a grass-roots level, Hec had risen from humble beginnings to have an appreciable influence over the future of many New Zealanders, Māori and Pākehā alike. Despite being a successful businessman who founded and ran a profitable bridge building company in Northland for over three decades, many of the people I spoke with considered that Hec’s most important contribution to his community has been a willingness to act as both a repository and a guardian of cultural knowledge. In his twilight years, he remains one of Te Rarawa’s great sources of knowledge for many issues, particularly those relating to the whenua. Others, such as Karl Johnstone, the director of New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts at Rotorua’s cultural tourist destination, Te Puia, have suggested that Hec’s ability to bring people together will be a significant part of his legacy. Indeed, the roll call of nations in attendance for the launch of his biography included Hawaiians, Tahitians, Cook Islanders, Samoans, Tokelauans, and half a dozen other Pacific nations. All of them had travelled to the shores of Doubtless Bay because of Hec’s standing in the wider waka community. It is fair to say he is held among his peers with a level of reverence seldom witnessed in this day and age.

For all Hec’s many achievements, it is possibly this last one, his ability to build bridges between indigenous nations throughout the Pacific, which he may become most widely known for. Those who named him Heke-nuku-mai-nga-iwi knew what they were doing. He wasn’t named by chance.