Matiaha Tiramōrehu: the first formal statement of Ngāi Tahu grievances against the Crown

Oct 22, 2017

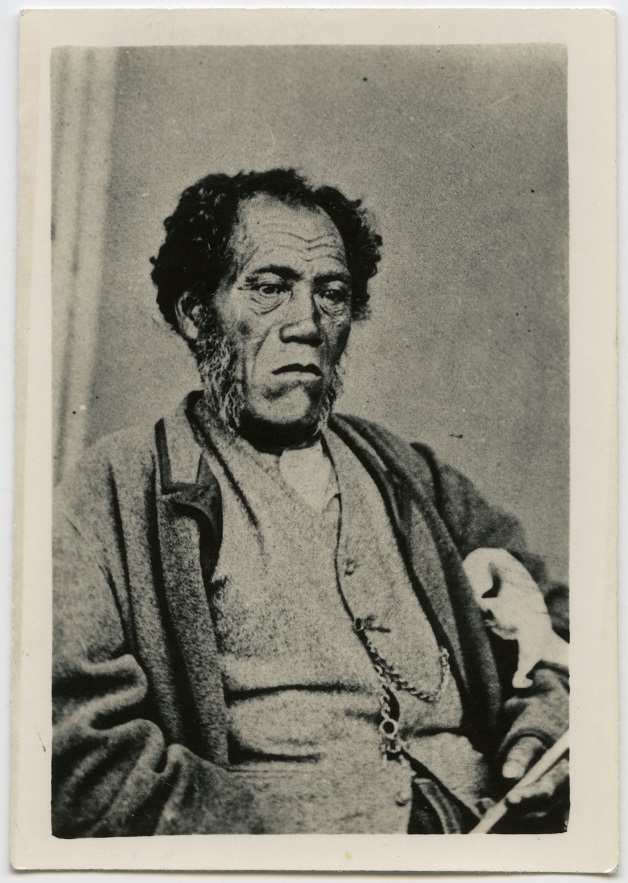

Matiaha Tiramōrehu, c.1860s. W. A. Taylor Collection, Canterbury Museum, 1968.213.136.

On 22 October 1849, the first formal statement of Ngāi Tahu grievances against the Crown regarding the South Island land purchases was made by the Ngāi Tahu rangatira, Matiaha Tiramōrehu. Just five years had passed since the first major purchase of Ngāi Tahu land at Otago, and only one since the signing of Kemp’s Deed (the purchase of Canterbury and North Otago). Tiramōrehu wrote to Lieutenant-Governor Edward John Eyre, seeking adequate compensation for the broken promises pertaining to Kemp’s Deed.

The letter, which can be seen here, focused on the inadequacy of the reserves and insisted that the land and payments promised be fulfilled. In an eloquent and impassioned protest Tiramōrehu wrote:

“This [is] the commencement of our complaining to you … we shall never cease complaining to the white people who may hereafter come here.”

Tiramōrehu further pursued the provision of schools and hospitals, and access to mahinga kai, which had been promised as a condition of Kemp’s purchase.

His vow to continue to seek justice stepped up in 1857 when he wrote a petition to Queen Victoria. The letter was signed by twenty-one other leading Ngāi Tahu chiefs of the time and asked that the Crown set aside adequate reserves of land for the people, as agreed under the terms of the land purchases.

Within the letter he proclaimed:

“This was the command thy love laid upon these Governors. That the law be made one, that the commandments be made one, that the nation be made one, that the white skin be made just as equal with the dark skin. And to lay down the love of thy graciousness to the Māori that they dwell happily and that all men might enjoy a peaceful life and the Māori remember the power of thy name.”

In the 20 years from 1844, Ngāi Tahu signed land sale contracts with the Crown for some 34.5 million acres, approximately 80% of the South Island, Te Waipounamu. The Crown failed to allocate one-tenth of the land to the iwi, nor did it pay a fair price, as it had agreed.

Over the ensuing seven generations, Ngāi Tahu continued to seek redress from the Crown. This movement, given the name Te Kerēme – The Ngāi Tahu Claim, became the basis of tribal identity and solidarity. Individuals, whānau and hapū tirelessly pursued the vision of Matiaha Tiramōrehu and through petitions, a series of commissions of inquiry, two years of Waitangi Tribunal Hearings and eventually four years of direct negotiations with the Crown, the Ngāi Tahu Settlement Act was signed in 1998. It brought an end to Te Kerēme and ushered in a new era of co-operation and partnership between Ngāi Tahu and the Crown.