A Puzzling absence

Apr 5, 2015

There is little evidence to support a sophisticated carving culture during the early centuries of Māori occupation of Te Waipounamu, says Tahu Potiki.

Above: Tauihu discovered at Mason Bay, Rakiura.

The East Coast tradition of Ruatepupuke bringing carving to the world from the House of Tangaroa was not familiar to the people of Ngāi Tahu. In fact the closest to a carving origin story one is likely to find in Ngāi Tahu tradition is that of Tama who encountered the gods and their full face moko. He demanded the same decoration, in order to become handsome and win his wife back.

Although not a carving that one might associate with a chiselled piece of wood, all the iconography and patterning is of a similar style. But rather than explaining the origins of carving it describes how, and why, moko came to be.

That said, we know that wood carving, as a concept, was included in the story of creation. Tāne takes Hine-ahuone as a wife, and they have a daughter, Hine-titama. Tane then sleeps with his daughter, but she has not seen him as he only visits at night. Hine-titama becomes inquisitive and she begins to question the carvings of the house. As they have the power of speech and they are referred to as ancestors, the story implies the pou are carved images; although considering the mythological context they could also have actually been the ancestors.

This same pattern of behaviour is repeated in the story of Paikea when his father is trying to determine the identity of the individual who desecrated a sacred object.

Āe ui rā ki te poupou o te whare, kāore te kī mai te waha;

Āe ui rā ki te maihi o te whare, kāore te kī mai te waha;

Āe ui rā ki te tuarongo o te whare, kāore te kī mai te waha.

He questioned the carved posts of the house, there was no reply;

He questioned the front gable of the house, there was no reply;

He questioned the rear panels of the house, there was no reply.

He receives no reply until he queries the carved tiki of the house, which is the tekoteko on the apex of the roof that represents an ancestor.

Āe ui rā ki te tiki nei, kia Kahutiaterangi.

He questioned the carved ancestor of the house, Kahutiaterangi.

There are other mythological references to elaborate carvings, but there is little evidence to support a sophisticated carving culture during the early centuries of Māori occupation.

The shaping of wood and stone was fundamental to the material culture of early Māori, and this included rude instruments for everyday usage. Objects such as bowls, fish hooks, canoes, cooking and gardening implements, and hunting equipment all required a carved component. We can trace the progression of the tools, implements, and jewellery that the original Polynesian migrants brought to these shores through the different periods of occupation as Māori adapted to the unique environment they had found themselves in. This adaption was critical for survival, but it also reflected an intimate understanding of local flora and fauna.

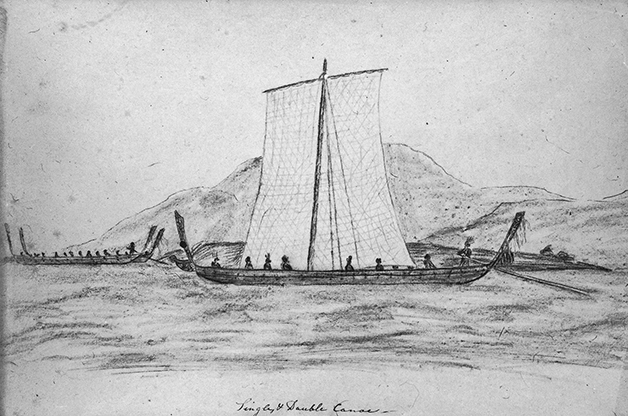

Above: Pencil sketch of single and double hulled canoe. Boultbee, John 1799-1854 : Journal of a rambler with a sketch of his life from 1817 to 1834, including a narrative of 3 years’ residence in New Zealand. Ref: qMS-0257-01. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22782017

By the time Europeans arrived, the entire forest and all the myriad species had been named, and their qualities were known. Some were ideal for canoes, some for carved pou, and others had the hard toughness required for military style weapons.

We know that Ngāi Tahu used a number of wooden weapons, as the story of the tuku whenua with Te Rerewa tells us that Ngāti Kurī originally offered weapons for land.

Ka a utua ki ngā taiaha me ngā huata me ngā tokoto me ka paiaka me ērā rākau patu takata a te Māori.

They offered taiaha, huata, tokoto, paiaka, and other fighting instruments of the Māori.

This shows there was knowledge of carving as well as a unique understanding of the qualities in one piece of wood. The paiaka was a type of tewhatewha where the blade was formed from the hard, knotty base of a tree where it becomes the root. In fact, paiaka actually means “the root of a tree”.

Another early story, that of the battles of Rakawahakura, recounts how, following an insult to his sister, an invitation is sent out to Raka’s enemy to help with an ohu, or working project, to prepare a garden. The sister, Te Ahu, said, “Haere ka tarai mai i te tahi kāheru māku,” – “Go and make a digging spade for me.”

All of her brothers went to the forest to gather the appropriated wood. They used this karakia:

He tomo whaka a Nuku,

He tomo whaka a Rangi,

He putanga,

He reanga,

Kei te reanga nui nō Rangi.

They selected maire, an extremely hard wood, took it back to the village, and in the morning performed rituals. They made a māipi, or taiaha, and named it Pai-okaoka. The whole village then proceeded to create kāheru, or spades, that had sharp blades. Once the work began, Raka’s party turned on the enemy and used the kāheru as weapons.

There are several different types and styles of southern weapons to be found in family collections and museums. All have been fashioned in one way or another, and some are decorated with elaborate carvings. On a small scale, they represent the classic recognised stylised imagery of the whākana and the whātero, the wide pāua shell eyes and protruding tongue.

Larger carved structures were less common. However, large canoes with carved decorations were evident in the later periods of pre-European Māori culture. Captain Cook and his crew observed many large canoes off the Kaikōura coast and around Banks Peninsula.

Whilst in Dusky Sound on their 1773 journey, the naturalist Forster noted these details of a canoe:

“…which appeared to be old and in bad order, consisted of two troughs or boats joined together with sticks tied across the gunwales with strings of the New Zealand flax-plant. Each part consisted of planks sewed together with ropes made of flax-plant, and had a carved head coarsely representing a human face, with eyes made of round pieces of ear-shell [pāua].”

Some of the earliest known images of canoes within Ngāi Tahu were drawn in approximately 1827 by sealer and diarist John Boultbee whilst he was living in Murihiku. He witnessed a canoe-borne war party quite possibly heading to Canterbury during the Kai Huanga war, and captured an image of what he saw. Although crude, the illustration clearly shows a carved tauihu and taurapa. Boultbee described them as follows:

“Some of their canoes were 80 feet long, these canoes have no outriggers and are about 3 feet wide; the lower part is one solid piece hollowed out and risen upon by a plank of 8 inches wide; at the stem and the stem are high pieces of carved wood.”

Le Breton, d’Urville’s official illustrator on the Astrolabe, captured an image of the Ōtākou settlement and shows what appears to be a double hulled canoe pulled up on the beach. It has a stylised prow, albeit much plainer than the elaborate carvings drawn by Boultbee.

It is much more reminiscent of the prow structure discovered at Long Beach, which is on loan to Otago from the Auckland Museum.

This is a much more modest depiction of a koruru-type figure with a protruding tongue, without the body or the stretched back arms and the decorative spiral.

Of interest is also the discovery of a tauihu at Mason Bay, Rakiura, which fits the Forster and Boultbee descriptions. It is an intricate prow decoration most likely carved using stone tools, which indicates a pre-European vessel.

The other large, carved structures generally associated with Māori culture are the ancestral meeting houses that were seen in abundance in the East Coast and Bay of Plenty areas by the earliest European visitors.

There are several oral traditions that refer to carved houses, such as Kura Mātakitaki, that was meant to have stood on Huriawa Peninsula in Te Wera’s pā by the Waikouaiti River. Kaiapoi was also reputed to enjoy a number of chief’s houses such as Te Huinga, which was “carved on both

sides from the top to the bottom; carved all over.” But due the destruction of the pā, actual material evidence has not been forthcoming.

Above: Le Breton, Louis Auguste Marie, 1818-1866. Le Breton, Louis Auguste Marie, 1818-1866 :Mouillage d’Otago. Nouvelle Zealande. Dessine par L. Le Breton. Lith. par P. Blanchard. Lith de Thierry freres, Paris. Gide Editeur. Paris, 1846.. Dumont d’Urville, Jules Sebastien Cesar, 1790-1842 :Voyage au Pole Sud et dans l’Oceanie … 1838 – 1842. Atlas pittoresque. Paris, A. Gide, 1846.. Ref: PUBL-0028-181. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23133411

There is archaeological research showing that large houses were built within many South Island fortified villages. At Pariwhakatau there are a number of house pits, the largest being 36 ft (11 m) long by 24.5 ft (7.5 m) wide. The tradition of the two houses Takutai-o-te-Raki and Te Tara-o-te-Marama being built by Tukiauau at Pariwhakatau to capture Manawa has some evidence to back it up when one considers the house positions and scale.

A 19th century account of the agricultural whare-kura at Kaiapoi, most likely provided by Natanahira Waruwarutu, provides an idea of the size of the houses used for communal purposes.

“Ko aua whare he kotahi kumi te roa, he mea anō kumi mā whā, a mā rima. Ko te whānui, e toru maaro, he mea anō e whā, a e rima maaro.”

“It was of considerable size – namely, from sixty to ninety feet long, and from eighteen to thirty feet broad.”

Despite these claims to houses of a grand scale, the earliest, recorded eye witness accounts, such as John Boultbee’s diary, tend to recall basic wooden structures, heavily thatched and of a modest size. He also describes the food storehouses at the chief Pahi’s village at the southern end of Te Waewae Beach, which, he states, “are usually stained with red ochre, as are also their houses: the pillars are ornamented with uncouth figures & faces of scarcely human aspect.” This certainly indicates that the ability to carve at this level existed amongst the people.

I am not aware of any eyewitness accounts of carved houses dating from early contact times, apart from the illustrated scene recorded by explorer and surveyor Charles Heaphy at the Taramakau pā site on Te Tai Poutini. The image shows at least one decorated house, although it is not clear whether the decorations are painted or carved. It is also a village that was heavily influenced by Niho and the invading North Island iwi who occupied the West Coast during the previous decades. It would not be surprising if the appearance of the village was influenced by northern styles.

Following European settlement we do see evidence of carved houses. The wharenui Tutekawa, carved by Patea Turi-Kautahi, possibly of Ngāi Tahu, was standing at Tuahiwi until it caught fire in 1879. According to the ethnologist Herries Beattie, in the early part of the 20th century several carved panels lay by the new wharenui. Beattie advised the Canterbury Museum, and the remaining panels and pou tokomanawa are held there today.

There may well be other examples of early carving, and we can see from images of the first and second Te Hapa o Niu Tīreni that there was a carved koruru over the maihi. The most elaborate house within Ngāi Tahu during the early years of the 20th century was Hohepa, which still stands at Mangamaunu. Despite it being a Catholic project and being decorated very much in the Rangitāne style, it was a Ngāi Tahu house used for Māori purposes.

The rest of the 20th century saw a number of carved houses emerge as part of southern Māori culture. Ōtākou Marae and its concreted exterior, Rehua Marae in Christchurch city, Te Rakitauneke at Waihōpai, Maru Kaitatea at Takahanga, and Karaweko at Ōnuku were all complete before the turn of the century.

The 21st century has already seen the emergence of new houses and a modern waka culture that will no doubt lead to further evolution of Ngāi Tahu decorative arts.