Across decades, oceans and generations

Mar 20, 2024

The Pacific Ocean that divides Aotearoa from Japan breaks just metres from where Tā Tipene O’Regan sits telling the story of a more than 30-year friendship between two men from two nations. As Kaituhi Jody O’Callaghan reports, Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa has always played a part in that bond.

In 1989, Tā Tipene was in the midst of Ngāi Tahu’s legal battle for settlement when Japanese businessman and philanthropist Masashi Yamada showed an interest in supporting the iwi. The primary motivation, he says, must have been commercial. Mr Yamada saw an opportunity to expand deepwater fishing opportunities out of the sea of Alaska into fishing for Hoki in Aotearoa, but it flourished into a friendship – or rather a brothership – that is now three generations deep.

The men’s whānau gathered in Tokyo in November as a sort of final farewell between the two, given Mr Yamada is now 101 years old. The 10-day trip was poignant – complete with tears, joy, haka, generosity, and friendship solidified between the two younger generations.

Mr Yamada’s right-hand man, Yoshikazu Narimoto, was convinced by Mrs Yoshie Yamaguchi, of the Yamada Corporation, to send a delegation to New Zealand in 1989 to look at possible property investment.

Tā Tipene O’Regan with his good friend Masashi Yamada.

Graham Kitson (Ngāi Tahu), a Christchurch-based businessman with a long-held interest in Japan, including attending university there, was asked to assist with showing the Yamada delegation potential investments in Te Waipounamu.

It was during this visit that Dr Kitson suggested if he was interested in fishing, Mr Yamada should meet Tā Tipene. It was a serendipitous meeting. Unbeknown to many at the time, the iwi was broke and about to abandon its legal fight for settlement.

“I was on the point of packing up our claim and locking it down because there was a good chance, we were not going to succeed in achieving a settlement,” Tā Tipene says.

He was going through the process of building the archival business so it could be stored for another generation to take on – the whole basis for establishing what is now an invaluable and enduring iwi resource.

A series of loans – multi-million dollars – from Mr Yamada during the 1990s gave the iwi the financial breath of life it needed to get through years of Waitangi Tribunal hearings and Crown negotiations. As the legal battle played out in Pōneke, where Tā Tipene lived, Mrs Yamaguchi gave him free rent in her Fendalton home as their Ōtautahi base.

“It was a great boon to us when Ngāi Tahu had no capacity to remunerate me. I was largely living and operating on a negative income for 11 years.”

Tā Tipene left his leadership roles at Wellington Teachers’ College to dedicate his time as chief negotiator of Te Kerēme (the Kāi Tahu claim), while his wife Sandra supported them financially by working as a nurse. He long suspected Mr Yamada “had a respect for what I was involved in doing for Kāi Tahu. I think it was a sense of an indigenous group finding its feet and its identity.”

Despite the need for translators in most conversations, their transactions are always at a personal level, with Mr Yamada referring to Tā Tipene as his “dear younger brother.”

The Yamada’s house Tā Tipene first visited in Yokohama had a tree growing among it.

“He explained to me the significance of not cutting that tree, as long as it grew up through it. All you could see was a big trunk growing up on the next two floors.”

Tā Tipene distinctly remembers all those years ago sitting and watching Mr Yamada’s young daughter putting on a ballet performance for them around the tree trunk.

Yamada senior never talked much about himself, but they learned snippets over time.

He never questioned Tā Tipene too much about his Kāi Tahu ancestry, which surprised him. But “it’s been an extraordinary relationship and at a personal level we started to really join that day, that first meeting in his office.”

Mr Yamada told Te KARAKA in 2014 about his first encounter with Tā Tipene.

“I was very taken by his passion and the way he talked about his culture and about Kāi Tahu, and I thought he was a fantastic human being. He touched me very much.

“I was very taken by his passion and the way he talked about his culture and about Kāi Tahu, and I thought he was a fantastic human being. He touched me very much.

That was the trigger of my interest for the Kāi Tahu, that very strong, passionate personality of his.

“And then I also remembered my mother’s words about how it was important to have friends all over the world, and I thought I should make this man my friend and support him. That was also part of the relationship, the human encounter.”

Tā Tipene’s relationship with the Yamada family not only allowed for the settlement, but it was the beginning of Ngāi Tahu Fisheries, which then capitalised Ngāi Tahu Property. While it was “the fight [for settlement] that gave me the passion for fisheries, it was Mr Yamada’s financial backing that gave the iwi the capacity to participate”, Tā Tipene says.

“We had quota, but no boats. All we were able to do was lease our quota to other people.” The Yamada Corporation helped the iwi buy its first boat, a big trawler shipped from the Sea of Alaska and renamed Takaroa, and its first fishing company hired its first crew.

“We went to work, and she failed. It came to nothing, because the boat was accustomed to the Sea of Alaska, didn’t have enough trawling power, and couldn’t perform in the same way in our waters.”

Boats for New Zealand deepwater are more like a tug, with two thirds of its body under water, Tā Tipene says. “But it meant the beginning of our fisheries opportunities.”

It wasn’t the last joint venture with the Yamada Corporation to fail either.

The two parties invested $500,000 each in a hotel at Lake Gunn on the Te Anau side of Hollyford Forks, powered by a hydro station on the hill above. Its managers were current Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu chief executive officer Arihia Bennett and her husband Richard.

It was a successful business in a beautiful location, until flooding caused a slip to push it over the road.

“It was one of those Fiordland weather events, where I first learned about the term ‘a yard of rain’,” Tā Tipene says. He travelled to Tokyo to deliver the Yamada share of the insurance payout during a luncheon in the early 2000s.

“The cheque went down on the table, and he pushed it across to me and said, ‘That’s the founding capital of the Yamada O’Regan scholarship fund’.”

During their recent trip in November, they had been discussing another donation from the Yamada group of $10,000 a year, which the iwi would match to fund an alumni group.

“On the last morning of our stay, he came to say goodbye to us at the hotel. He passed a blue folder to me with documents inside giving us a contribution to the fund of $1 million. Ben (Bateman) now has the challenge of how to match it. We may have to do it over time,” Tā Tipene grins at what a good problem it is to have, all going towards rangatahi futures.

Of the many financial contributions by the corporation, education is important to Mr Yamada, so whānau have the chance to overcome their “postcode lottery” to enrol tamariki and rangatahi in boarding schools. Ben Bateman, chief operating officer, says he never expected such a large donation “at this point in time.”

The iwi is reviewing its mātauraka strategy, and the latest Yamada fund will be part of that.

Ben, who travelled to Tokyo for the reunion between the two families, says the friendship between the two men is the core of any business they’ve had.

“It was a privilege to witness it,” he says. “They want to take this into the next generation, which is pretty humbling because of the relationship that Tā has built up.”

The elderly Yamada “was highly emotional at every meeting.” One hui turned into three because everyone enjoyed each other’s company so much. The gravity of it being the final meeting between the kaumātua likely had something to do with it too. The event meant so much to the O’Regan whānau, who paid for Tā Tipene’s grandchildren, his daughter Hana’s children to join him on the 10-day trip along with Hana and Miria.

The Yamada-O’Regan friendship will continue through these younger generations, and through Tā Tipene’s close friendship with Mr Narimoto, who is credited with facilitating their introduction.

Takerei Norton, manager of the Ngāi Tahu Archive and a proud former rugby player, got the chance to go to the Tokyo World Cup in 2019, along with Hana, where they met Yamada junior, Shinji-san.

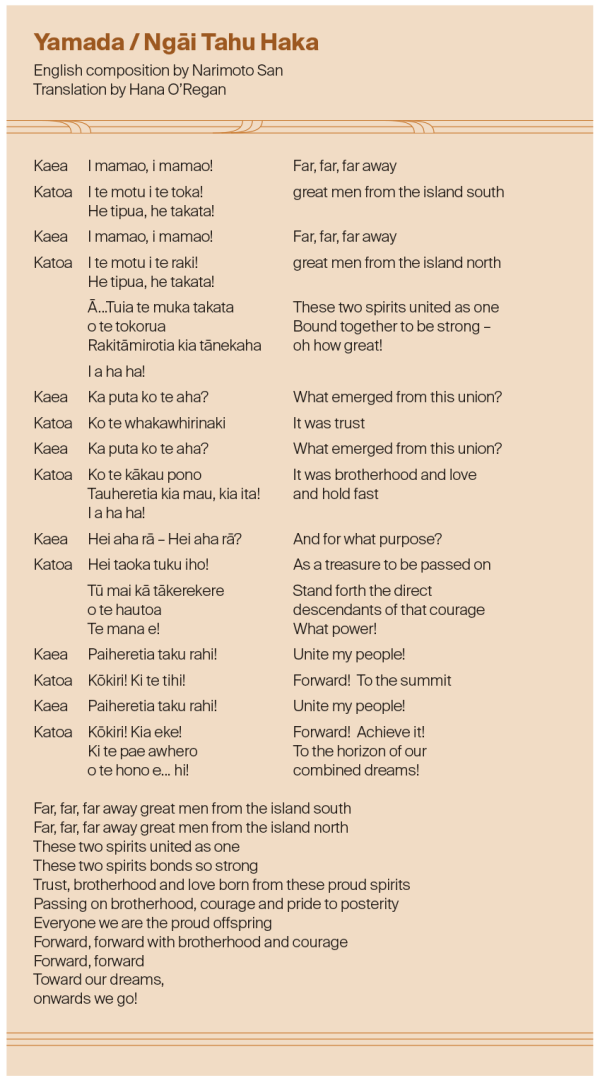

Narimoto was fascinated by haka and asked Hana how one was composed. Hana suggested that he could provide some thoughts about what he might like to say in a haka, and she would be happy to translate them into te reo Māori. On the last evening of the trip, Narimoto stood up to read out what he called his ‘homework’ and proceeded to recite the most beautiful poem he had composed on the Yamada O’Regan relationship. Hana translated his words into te reo Māori, and upon her return to Te Waipounamu, asked Charisma Rangipunga’s son, Taiki Pou to put a raki and actions to it which he skilfully did. Hana and her children then learnt Narimoto’s haka to perform to Yamada.

“He’s the first Japanese author of a haka Māori that we know of,” Tā Tipene says.

The words of Narimoto’s haka were handwritten on parchment scrolls in te reo, Kanji script and English as a koha to Yamada and family on the recent trip.

Shinji-san has shown himself to be the successor of the Yamada group, Tā Tipene says. It was during this latest trip where three generations of each whānau met.

Shinji-san has played an important role in maintaining the relationship between his father and Tā Tipene and remains connected with this island where he hopes to spend more time, Tā Tipene says.

It would be one more way in which the two whānau and iwi can continue their lasting bond, in the whenua Yamada senior fell in love with on that first visit in 1989.

L-R – back: Ben Bateman, Miria O’Regan, Hana O’Regan, Te Rautawhiri Mamaru-O’Regan, Manuhaea Mamaru-O’Regan, Sara Yamada, Yoshikazu Narimoto, Masanobu Yamada; left to right – front: Lady Sandra O’Regan, Tā Tipene O’Regan, Masashi Yamada, Shinji Yamada Yoko Yamada.