He Aitaka a TāneSheltering toetoe

Jul 5, 2012

Toetoe are our largest native grasses. They are hardy, abundant and commonly found anywhere from swamps and riverbanks to sand dunes, forest margins and dry hillsides between sea level and the subalpine zones of Aotearoa.

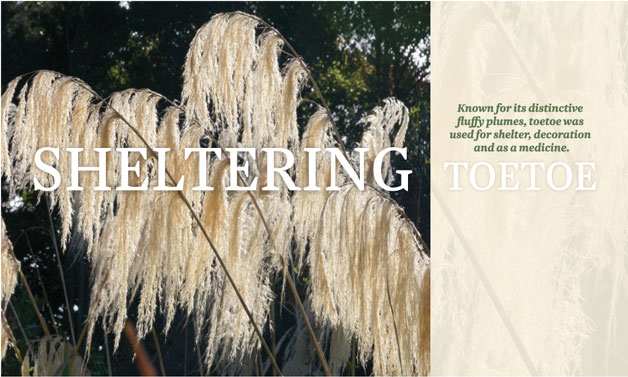

This plant is best known for its long, straight flower stems and fluffy creamy-white plumes that wave like flags in the wind.

According to some southern sources, traditionally Māori harvested these flower stems, known as kākaho or pūkākaho, to line the walls and roofs of whare.

Pūkākaho were cut at specific times of the year and much effort went into finding long, light-coloured stems in preference to deep yellow stems, according to Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research.

Pūkākaho of an even colour, size and length were used to make tukutuku panels, a very neat ornamental latticework of reeds bound together with harakeke, kiekie or pīngao to line the walls or sometimes ceilings or partitions of wharenui (meeting houses).

In Murihiku wharenui, these handsome reeds were thatched with pātītī (tussock), perhaps to better insulate the buildings in winter from the notorious southerlies off the Southern Ocean.

In his interviews of Ngāi Tahu people in the 1920s, Southern Māori ethnographer Herries Beattie recorded a technique used to create alternating black and white rings in pūkākaho by wrapping harakeke leaves around the stems and scorching them over a fire.

Sometimes the stems were steeped in mud to stain them black, and then alternated with clean white reeds in the final design for a contrasting pattern.

In Traditional Lifeways of the Southern Māori, Beattie recorded that pūkākaho were sometimes bound and thatched with harakeke and raupō on the exterior walls of whare pōtaka (round houses) as well.

Roofs were sometimes double-thatched with raupō and toetoe to make them more waterproof, or perhaps to better insulate them.

While not elaborate, these huts were regarded as good enough to sleep in, Beattie said.

He also describes construction of pāhuri, a temporary shelter used for fishing, birding and rafting trips, and made from the branches of trees, toetoe, kōrari (harakeke flower stems), pātītī, reeds or any other material available. Vines or harakeke leaves were used to bind these structures together to provide a quick shelter from the elements.

Beattie’s contacts told him the old people usually slept on the ground, on a bed of soft vegetation such as kōhungahunga (tow of flax), pātītī, rauaruhe (bracken fern), toetoe or raukiokio (a large fern similar to a ponga).

It seems Māori children were every bit as resourceful as their descendants today when it comes to the art of invention.

Boys used bows made of kareao (supplejack) and mata (arrows) made from the stalks of toetoe or aruhe. They also made a throwing dart from pūkākaho, that Beattie says could be projected 200 yards with the help of a throwing stick.

Pākau (kites) and rama (torches) were also made from pūkākaho.

Toetoe leaves are renowned for their serrated cutting edge, and were used in traditional Māori medicinal practices of blood-letting to score the skin.

After removing the leaves’ sharp edges, Māori sometimes used them for weaving mats or baskets, or to cover food in the umu. However, harakeke was more commonly used for these purposes.

Feathery toetoe flower plumes were used as a dressing to stem the flow of blood from wounds. They were also used as a poultice on burns and scalds.

In Māori Healing and Herbal, Murdoch Riley records historical accounts of pūkākaho stems being heated in water, and the hot liquid being used to treat wounds from wooden spears or lances. Sometimes the wound was then plastered with mud or clay to seal it from the air. Alternatively, toetoe was used instead of mud.

Records show the roots of toetoe, tātarāmoa or pirita (kareao or supplejack) were used to treat intestinal parasites. A piece of the toetoe stalk, roasted over a fire then chewed, was said to cure toothache.

Chewing the tender young shoots was reputedly a cure for yeast infections, kidney troubles, and urinary, bladder, and bowel complaints including diarrhoea.

Riley explains how the hollow stem of the toetoe was used to symbolise the acquisition of knowledge at the wharekura (school of learning).

The tohunga used the pūkākaho stem to trickle water into the left ear of his pupil as a symbolic way to confirm that his knowledge was imparted orally. Similarly, the pupil chewed on the root end of a particular type of toetoe while learning incantations, to help him memorise them, and to prevent him from giving those secrets away to others.

There are five species of toetoe. The largest is confined to Northland, the Bay of Plenty, and Waikato. One is found south of Tauranga, and two are widespread nationwide. The fifth grows only in the sphagnum moss and peat swamps of the Chatham Islands.

All are large, stout tussocks between one-and-a-half and two metres tall; with sharp-edged leaves and upright flower heads between two-and-a-half and six metres tall.

There are two introduced species of pampas grasses from South America that are the same species and similar in appearance to toetoe, but they spread freely and are regarded as pests in northern parts of the country.

These days toetoe is valued by farmers and gardeners alike for low shelter, because it is unpalatable to stock, resilient to strong winds and salt spray, can tolerate water-logged ground conditions and is reasonably drought-tolerant. Toetoe is easily grown from seed or propagated by dividing an established plant.