He Ōhākī a te Rakatira

Dec 20, 2020

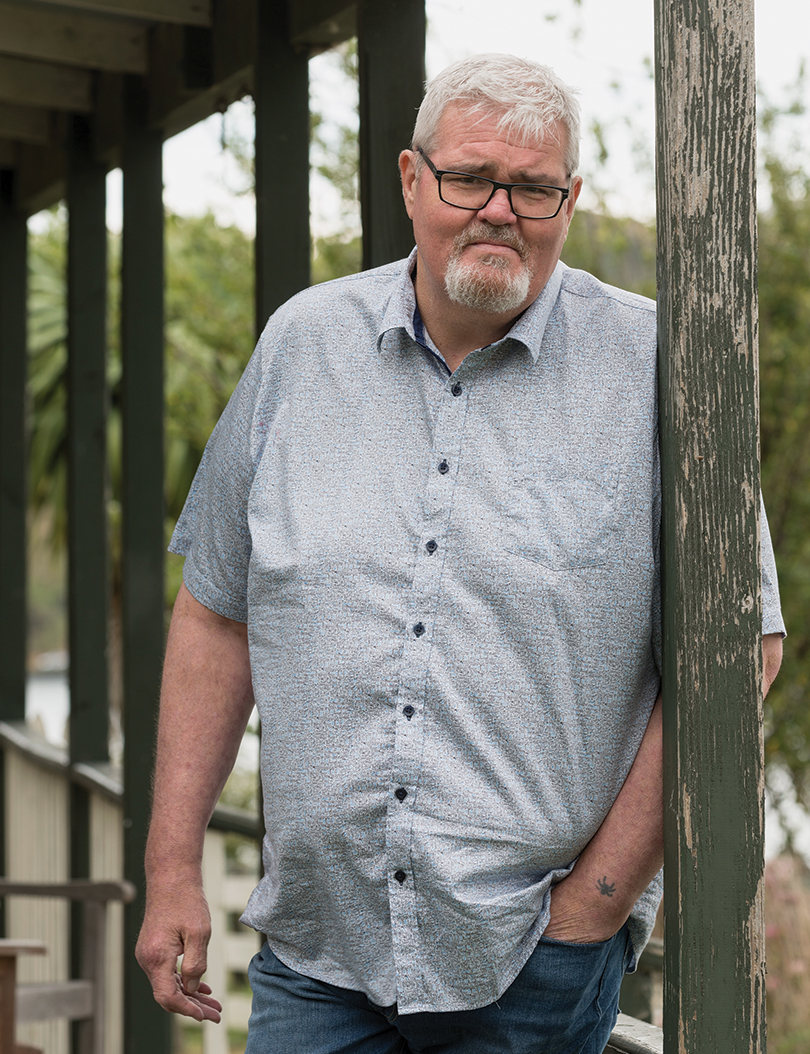

Tahu Potiki (1966-2019) was deeply versed in the traditional history of Ngāi Tahu and a recognised authority on our treasured manuscripts, many of which were published in translation in TE KARAKA. Tahu was Chief Executive of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (2002-2006) and subsequently served as the Ōtākou Representative on Te Rūnanga until his death. From 2007 onwards he regularly contributed articles on Ngāi Tahu and wider Māori questions to the Christchurch newspaper, The Press. These were noted for their erudition, balance and well-informed insight. Early in 2019 he sent Tā Tipene O’Regan the draft of the article published here asking for comment and seeking his view on why it hadn’t been published. It is with some satisfaction, then, that we are able to bring to our readers the final essay of this noted rakatira and thought leader of our people.

In 1853 the nascent Otago settlement was grappling with the implications of the New Zealand Constitution Act which had been passed by the Parliament of Great Britain the previous year. Governor Grey introduced the Constitution by Proclamation in January 1853. It allowed for the establishment of a New Zealand General Assembly as well as creating six provincial councils with significant regional powers. It set the country on a pathway to democratic elections and provincial elections were the first to occur.

To be eligible to vote you needed to be male, over 21 years of age and to own or lease freehold land worth 50 pounds or more. The eligibility of Māori was not in question. Māori males who met the criteria were eligible to vote just as other citizens which led several Otago based Ngāi Tahu to enrol for the Otago Provincial Council elections. This registration led to quite some consternation amongst the settler leadership.

Local newspapers reported the many reactions from the new settlers with the general sentiment being that “the general enfranchisement of the Maories would be a most disastrous event for New Zealand.” Further claims were made stating that giving the Natives the vote was preposterous, dishonourable, immoral and would immediately subject Māori to the risk of bribery. Also woven into the outrage laden correspondence were suggestions that Māori were being manipulated and were not enrolling by their own free will.

These ideas were fuelled by notions of an anti-Cargill conspiracy led by Walter Mantell. Mantell, well-known to local Māori, had fallen out with Captain Cargill over the administration of Crown Lands but Mantell had the confidence of Governor Grey. Cargill believed that both Grey and Mantell were trying to undermine Settler authority and that Mantell had used his influence with Māori to register local Ngāi Tahu to vote.

In the build-up to the elections there were 78 Māori registered to vote in Otago until Cargill and Macandrew fought back. It was not once suggested that Māori may have been acting of their own free will and that their pursuit of enfranchisement was a stand for citizenship. It was only ever seen as poor, ignorant puppets being manipulated by others to “swamp the European population” and to serve Pākehā political ends. Cargill claimed that “a more unscrupulous attempt to pack an electoral roll has never been attempted.”

They ultimately sought the advice of the Attorney-General who declared that Māori were unable to vote as they owned land in-common under customary native title and that “All persons qualified to vote according to that Act must derive their qualifications from land or buildings on land held by some tenure known to the law of England.” If they lived on land with unextinguished native title then Māori could not vote.

At the forefront of this collective societal paranoid prejudice is the loathing of Māori Mana Motuhake or Tino Rangatiratanga. The idea that the displaced tangata whenua, whose power was usurped by an imperialistic notion of Western superiority, may want that power back if the current regime achieves enlightenment and offers to relinquish said power, is both abhorrent and an absurdity to the average Kiwi.

The Ngāi Tahu of Ōtākou, Purakaunui and Taiari secured legal representation and argued that they were, in fact, freeholders, basing their argument on Article Three of the Treaty of Waitangi. Their lawyer proffered that the Treaty had the force of an Act of Parliament and this entitled Māori to all the priviliges of British subjects. His argument failed due to the fact that, as British subjects, they needed to live on land recognised by British law.

Although the overall response was convoluted, at the core of the Otago settlers’ concerns was the possibility that Māori democratic participation would seriously disrupt the settlers’ comfortable assumptions – that following the election, the Otago Scottish settlers would remain firmly in control of their New Edinburgh Colony.

The Attorney-General’s decision became the foundation position nationally, determining that the comprehensive enfranchisement of Māori was unattainable, and that only those who held individual title were entitled to vote. This excluded the vast majority of Māori from the machinations of a Government that then set about making law which undid the fundamental protections inherent in the Treaty of Waitangi. The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 abolished the Crown’s pre-emptive right and opened the flood gates for settler acquisition of land which saw the transfer of 95 percent of all Māori land into European hands by 1900.

The establishment of the Māori seats in 1867 was seen by many as a progressive move for the time. It created a voting right that was not correlated to the Western notion of property rights which was utterly unprecedented across the British Empire. It allowed a vehicle for a Māori voice in Parliament and participation in the affairs of government. It did not, though, restore the necessary political power to Māori that would allow them to resolve the loss of land, language and sovereignty by which they had been afflicted during the previous decades and the century to come.

Every move had been made to secure settler power. Alien notions of tenure reinforced by layers of legalistic barbed wire and bureaucratic gobbledygook kept any threat from the natives well at bay. The real seats of power – a democratic majority or access to vast amounts of capital – were denied to Māori until such things no longer had the ability to swing the balance of power in their direction.

In modern New Zealand full voting rights for Māori and a minute share of the nation’s wealth pose absolutely no threat to the colonial settler power which still squats upon Aotearoa.

This week’s [3 April] voting down of the Canterbury Regional Council (Ngāi Tahu Representation) bill sought to extend the provision for direct Ngāi Tahu representation to the Regional Council, which was a great disappointment for the local iwi. The past 10 years have delivered a sense of promise to Ngāi Tahu that a further step towards Treaty-based partnership could actually be realised. The post-earthquake environment invited a different type of relationship with iwi that was clearly noticed by all as Ngāi Tahu took a leadership role standing side by side with others that hold a civic mandate. They were united in their mission and the iwi committed its time, people and resources to achieve a solid community outcome for all citizens. Those of us from outside Christchurch watched with interest as a different type of dialogue emerged in the city.

But despite the change in bicultural climate the true test of the relationship seems to have failed at the first hurdle. Everything was going famously until the question of actually consolidating a power sharing opportunity was presented to those who would have to relinquish it. Environment Canterbury (ECan) was admirable in their resolve as were local politicians who recognise the value of a solid long-term partnership.

But both Gerry Brownlee and Shane Jones suggested that the strength and economic might of Ngāi Tahu should be sufficient for the iwi to be able to orchestrate a successful election campaign that would secure a seat at the table. The staggering naivete of comments like this, from two men whose intellect and capability I have generally respected, is flabbergasting.

They are very aware that any significant Ngāi Tahu lobby that campaigns with some integrity, and reflects what the iwi actually believes and would like to achieve for themselves and the community, will not appeal to the majority of voters. As High Court Justice Matthew Palmer once wrote, “However loudly Māori voices are now heard in politics, it is still the majority who rules the Sovereign Parliament.”

Despite the fact that in recent weeks it is as if the entire New Zealand population has become more ‘woke’ to our Euro-centric society, it remains unclear that there is any ownership of the insidious prejudice and institutional racism that infiltrates every facet of New Zealand life. Even closer scrutiny will expose the myriad of culturally biased constructs that diminish opportunities for those outside of the mainstream culture and awaken fear in the form of wicked preconceptions that continue to backlash upon and disadvantage Māori throughout our public institutions. At the forefront of this collective societal paranoid prejudice is the loathing of Māori Mana Motuhake or Tino Rangatiratanga. The idea that the displaced tangata whenua, whose power was usurped by an imperialistic notion of Western superiority, may want that power back if the current regime achieves enlightenment and offers to relinquish said power, is both abhorrent and an absurdity to the average Kiwi.

Whilst Parliament has rejected to even consider the proposal for direct Ngāi Tahu appointments to council, citing some colour-blind ideology that denies the origin of their privilege, ECAN has shown that they believe things could be different. I sincerely hope that local solutions to deliver an equally effective recognition of binding Ngāi Tahu mana in the governance process are now on the table for debate.