"Help from above" Air Ambulance services in Te Waipounamu

Mar 20, 2024

Nā Dr Michael Stevens

In late April 2011 my poua, Tiny Metzger, had a “bit of a turn” on our tītī island. He’d been out in the sun most of the day swinging an axe and a slasher as if he was 28 years old … but he was 78.

And he hadn’t kept properly hydrated. Later that night, once he’d finished plucking tītī, he collapsed. His pulse was weak, very weak. He genuinely thought his number was up. “If they come for my passport,” he told my mother, “you need to get a feed of tītī to Rānui Ngārimu, and another feed to …”

Fortunately, the people who came for Tiny that night were not our tīpuna, but paramedics in a helicopter. He was taken to Southland Hospital and stabilised. And although his ticker has given him quite a bit of gyp since, he went on to teach my three children to weave kete and prepare rimurapa for our pōhā-tītī, catch and gut pātiki, and much else besides.

As I write this article, we have just celebrated his 91st birthday.

We owe that celebration to the air ambulance service operating across Te Waipounamu. Other local whānau Kāi Tahu have similar stories. Five years earlier, for example, another of those helicopters retrieved survivors from the ill-fated Kotuku who made landfall on our tītī island. That helicopter then joined others in aerial searches, in very challenging Foveaux Strait conditions, for missing whānau members.

These two examples demonstrate the benefit that mutton-birders specifically derive from air ambulances, but Kāi Tahu reliance on this service goes much further than that. These amazing machines and the highly-skilled people who operate them provide a lifeline for sick and injured fishers, hunters, and those living in isolated settings such as Rakiura and Arahura: professions, past-times, and places at the heart of flaxroots Kāi Tahu life.

Despite that, what do any of us really know about the air ambulance service working across Te Waipounamu?

For nearly three decades, HeliOtago (based in Dunedin), GCH Aviation (Christchurch), and Southern Lakes Helicopters (Te Anau) each provided air ambulance services in their respective areas. However, in October 2016, faced with the threat of an international competitor, existing providers banded together and established a joint venture company: Helicopter Emergency Medical Services New Zealand Ltd. HEMS for short. This initiative worked, and HEMS now holds the South Island-wide contract for helicopter air ambulance services with Te Whatu Ora (Health New Zealand) and the Accident Compensation Corporation.

This contract is arranged and monitored by a commissioning agent within Te Whatu Ora, the Ambulance Team (formerly known as the National Ambulance Sector Office or NASO).

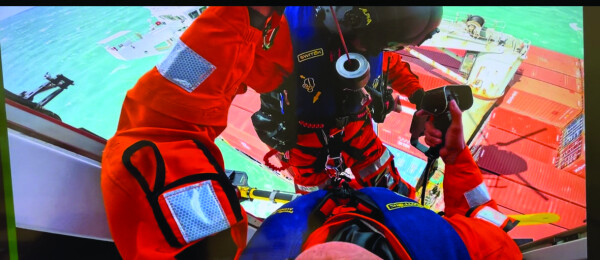

Paramedic Steve Pudney during a rescue mission at sea.

HEMS then subcontracts its operational responsibilities to HeliOtago, GCH Aviation, and Southern Lakes Helicopters. By such means, the organisation has bases in Dunedin, Queenstown, Te Anau, Christchurch, Greymouth and Nelson. This geographical sweep is crucial because HEMS is responsible for the whole of the Te Waipounamu, Rakiura, the Sub-Antarctic Islands, and the associated marine and coastal regions. In other words, the entire Kāi Tahu takiwā as well as Te Tauihu.

Despite these subcontracting arrangements, it’s not been a case of simply business as usual. The HEMS model is driving even greater consistency and enhancement of service delivery. This includes developing a network of operational Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) routes for helicopters. These are “highways in the sky,” as HeliOtago’s CEO, Graeme Gale, puts it. “IFR is for when you’ve got a dirty, horrible night and you can’t see much of anything. You rely solely on your instruments.”

That one investment has enabled HeliOtago to reach somewhere between 15 and 20 per cent more patients a year. That said, IFR’s potential varies across the HEMS catchment. On Te Tai Poutini, for example, the Southern Alps imposes very real limits on its usage.

Its rollout there will nonetheless prove valuable in some contexts.

However, it will be used in concert with fixed-wing air ambulances, which GCH Aviation’s CEO Daniel Currie and his whānau have been providing to the region for decades.

HEMS has also coordinated a growing network of community-funded heli-pads, established senior clinician-supported paramedic helplines, simulation-based learning tools for difficult clinical procedures, and advanced remote satellite-based communication systems. The company has also acquired sophisticated diagnostic equipment for its aircraft. This culture of excellence and ongoing improvement gives real meaning to HEMS’ four foundational principles: Trust, Respect, Integrity, and Compassion. It also responds to the ambulance team’s expectation that providers like HEMS help “improve services, and find system efficiencies.”

Another of the strategic priorities is that emergency ambulance services contribute to better and more equitable health outcomes for Māori.

For all of those reasons, HEMS has established a People, Communities and Culture Adviser. I was delighted to accept that position in May. This role provides the HEMS board with governance advice to:

- improve equity of access to health services for remote, rural, and disadvantaged South Island communities

- create culturally-safe HEMS workplace; and

- develop Māori and Pasifika career opportunities within the South Island’s air ambulance service.

In other words, this role can help advance some Kāi Tahu health targets and health workforce aspirations. Even so, the role has a much wider brief. For example, one of NZ’s fastest growing Pasifika populations is centred in Oamaru which, in per capita terms, is now more Polynesian than Auckland. Fold in tourism hotspots such as Queenstown and Kaikōura, and Te Waipounamu is more culturally diverse than many people realise.

Nelson based Paramedic, Kodee Pori-Makea-Simpson.

However, the supreme challenge for HEMS relates to land size and population base. The South Island is 30 per cent larger than the North Island, but has a much smaller population: roughly 1.1 million versus 3.6 million. Simply put, our air ambulance service has, on average, much longer mission times, and therefore places higher demands on paramedics for patients in need of acute care. Long story short, HEMS has to be particularly smart with where and how it invests its limited resources.

As a result of my work with the HEMS board, the company recently developed “Project Equity”. This has one overarching goal: to enhance patient clinical outcomes through improved service delivery. Through this initiative, we are seeking to understand whether or not current services contain barriers preventing optimum medical outcomes.

If such barriers exist, we will implement and monitor solutions aimed at removing them. While this focus is built around individual patient care, individuals belong to whānau, and whānau to communities; Project Equity represents HEMS deepening its commitment to society.

As well as the demographic context to all of this, which includes the challenges of an ageing population, HEMS is also grappling with big health sector reforms, opportunities and constraints of emerging technology, and an increasingly difficult climate. Extreme weather events, for example, could drive higher demand for HEMS services but also make it harder to operate aircraft in.

How might Kāi Tahu communities, Papatipu Rūnaka, and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu position themselves to enrich and protect vital air ambulance services? Part of the answer, I hope, is by working with HEMS to develop pipelines for Kāi Tahu paramedics and pilots.

I think there is also potential for Te Tāhū o te Whāriki and Te Kounga Paparangi, the Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Climate Change Strategy and accompanying objectives, to consider the strategic importance of air ambulances.

However, Te Tauraki, our Iwi Māori Partnership Board (IMPB), probably has the most direct and relevant role to play in the first instance. That is a key way of ensuring that the particular reliance that Kāi Tahu has on air ambulance services is explicitly woven into locality plans currently being developed across our takiwā.

As HEMS looks to expand its Māori workforce, it’s worth highlighting some of the talented crew already on its books. This includes pilot Clayton Girven (nō Ngāti Maniapoto) at HeliOtago, and paramedics Steve Pudney (nō Ngāi Tahu) and Libbie Faith (nō Ngāi Tahu rāua ko Ngāti Kahungunu) at GCH Aviation’s Christchurch base, and Kodee Pori-Makea-Simpson (nō Te Ātiawa, rātou ko Ngāti Mutunga ko Waikato-Tainui) at its Nelson base.

Rescue mission at sea.

Clayton Girven hails from Te Kuiti, but was raised in Warkworth and across Northland. After schooling at Whāngarei Boys’ High and Palmerston North Boys’ High, he joined the army in 1994, aged 18.

As an armoured vehicle crewman, Clayton served for six years, including tours in Bosnia and East Timor. And it was his time in East Timor, witnessing Black Hawk helicopters in action, that instilled a hunger to become a pilot. Clayton left the army and completed his flight training with Massey University, which led to charter and commercial work. He flew helicopters from tuna boats across the South Pacific and with a specialist power line company in Australia.

Returning to NZ, Clayton worked in air ambulances across the North Island, but in 2011 joined HeliOtago, attracted by the company’s good reputation and the challenging environment.

“My wife and I both absolutely love this part of New Zealand,” he says. “Most of all though, I really enjoy my job. Working alongside talented and compassionate people and providing medical assistance to those in need is very satisfying.”

Steve Pudney’s whakapapa comes out of Arowhenua and he was raised in a big outdoorsy whānau at nearby Fairlie. Deeply passionate about horses, he rode them all around Te Waipounamu, Australia and the United States. After he returned home for good, Steve worked as a carpenter, but a chance encounter with an old friend, and encouragement from his mother, led to a change in direction and training as a paramedic: first as a volunteer, then, from 2012, in a full-time paid role with Hato Hone St John.

Steve Pudney (right) with Critical Care Paramedic, Justin Adshade.

Along the way, he’s completed several qualifications including a Diploma in Ambulance Practices, Bachelor of Health Science (Paramedic), and a Postgraduate Certificate in Critical Care Paramedicine. In November, 2017 Steve qualified as an Intensive Care Paramedic (ICP). This is all no mean feat for someone who describes himself as practical more so than academic.

Earlier this year Steve sought to once again stretch himself and grow his skillset by joining HEMS and working in the air ambulance sector. He and his wife and daughters live inland at Sheffield. This country backdrop helps to explain Steve’s passion for HEMS, as he says: “When things go wrong in rural settings, they can go really wrong. Whether a medical event on the farm or an accident in the bush, city hospitals can feel even further away than usual.”

Air ambulances provide the crucial link. “We are literally a lifesaving service. I feel incredibly privileged to serve our community through HEMS and GCH Aviation which are such professional organisations.”

Libbie Faith grew up in North Otago and South Canterbury as with previous generations of her whānau. Her Taua was raised at Moeraki; her parents in Temuka. After a childhood in the Waitaki Valley and primary school at Te Kohurau, Libbie headed to Craighead Diocesan School in Timaru. She has spent most of the past two decades living and working in Taupō: as a bungy-jump master and, with consequent working at height qualifications, in the oil and gas industry doing the “FIFO” thing, mainly to Perth.

Libbie Faith grew up in North Otago and South Canterbury as with previous generations of her whānau. Her Taua was raised at Moeraki; her parents in Temuka. After a childhood in the Waitaki Valley and primary school at Te Kohurau, Libbie headed to Craighead Diocesan School in Timaru. She has spent most of the past two decades living and working in Taupō: as a bungy-jump master and, with consequent working at height qualifications, in the oil and gas industry doing the “FIFO” thing, mainly to Perth.

But as her daughter hit her “tween” years, Libbie was less keen on the travel involved. She had also been volunteering with Hato Hone St John and trained as an Emergency Medical Technician. This led to employment with the organisation lasting nearly four years.

Libbie then joined the Taupō Rescue Helicopter, where she completed just over four years. In September this year Libbie moved back home to Te Waipounamu, picking up a flight medic role with HEMS at GCH.

“I am really loving being back home,” says Libbie. “Taupō is amazing but home is home.”

She also highlights the commitment that HEMS and GCH have to clinical training as one of things having made her move south so worthwhile. Looking ahead, Libbie is keen to see how HEMS can further help meet health needs in remote and rural communities, especially whānau Māori. As she says, “This an area where improving Māori outcomes is good for the whole country.”

Kodee Pori-Makea-Simpson is a proverbial “Mozzie”: born and raised in Sydney to a Māori mum and an Australian dad. Completing her degree in paramedicine, Kodee subsequently practised in rural Victoria, including Phillip Island south-east of Melbourne. With a strong ethic of duty and deep love of problem-solving, paramedicine was a natural career choice.

In 2018, her mother shifted home to Waitara and Kodee was visiting every two or three months. However, COVID-19 put paid to those trips. Her mother and wider whānau felt very far away, so Kodee made a permanent shift to New Zealand 18 months ago.

After an initial stint with Hato Hone St John in Whanganui, she secured a position at GCH’s Nelson base. She loves the Te Tauihu region. As Kodee says, “The natural environment here is incredible.” However, she finds Nelson is also surprisingly isolated: “It’s sort of like a city in the middle of nowhere. And you really see that from the air.”

That observation helps to explain the critical role of paramedics and air ambulances in northern Te Waipounamu. “We run lots of flights between health centres,” she says. As in Australia, Kodee takes a huge sense of pride in her work with HEMS. “I really value the opportunity to work with and advocate for people, especially those in rural settings, as they navigate complex health system processes, usually at very vulnerable times.”

I titled this article “Help from Above” in recognition of the lifesaving role played by air ambulance services across Te Waipounamu, its surrounding islands and waters. The title is clearly a pun. This is not a “hand-of-God” service. No deity is reaching down from the heavens bringing material aid to acutely unwell patients; it’s HEMS, a service developed by South Island people for SI communities. It is, therefore, “Help from Within.” I hope we have it within us all to ensure this service continues.